COFFEE WITH

CAROLINA OBREGON: “IT’S ABOUT USING SCIENTIFIC KNOWLEDGE AS A DESIGN TOOL”

Name: Carolina Obregon

Profession: Biodesign Expert and Professor

Nationality: Colombian

Instagram: @carro.obregon

LATINNESS: Carolina, I’ve known you for a while as an academic, but you actually studied fashion design. Is that right?

CAROLINA: I did Fashion Studies at Parsons and worked in the fashion industry in New York for about ten years. First, for some designers, and eventually, my own accessories brand. I created the pieces in Guadalajara, Mexico, and then sold them in New York. It was a very artisanal process.

After giving it a lot of thought, I realized one of the things that always concerned me was the lack of ethical processes in what I was doing, specifically purses and handbags. I love fashion and was passionate about it from a very young age, however, when you’re inside, you notice things that aren’t so cool.

I returned to Colombia, then moved to Los Angeles, where I worked for Coach. The brand had an abysmal waste in its processes. They manufacture in China, then ship everything to Florida to put “Made in the USA” on it, and then return it to China. It’s crazy! The purses arrived full of plastic and packages.

LATINNESS: Not sustainable….

CAROLINA: It’s not sustainable at all. That was in 2010. At that time, they launched a Master’s degree program in Sustainable Design at Aalto University in Helsinki, Finland. I won a scholarship and went to study at an older age than the other students. It was eye opening, because Scandinavians, in general, are very aligned with nature, with their environment and with other human beings. They respect them.

Finland is a country with thousands of forests and lakes, and there are many activities around this. When I entered university, I realized that design could generate more sustainable processes from its extraction, a concept I understood, albeit empirically.

That’s when I began to understand how I could begin to apply it within design. When I wrote the thesis I decided not to make a collection, nor a product, because I was in a political process in which I said, “I’m not going to give life to something that will end up in my closet.”

Through my research I met Juan Hinestroza, a professor at Cornell University, perhaps one of the people with the most expertise in textile nanotechnology, and he’s Colombian, from Santander. A brilliant and very kind human being.

We became very good friends through the thesis. He came to Helsinki and we continued our friendship. When I finished, I went to Switzerland. I wasn’t planning on going back to Colombia, but the Jorge Tadeo Lozano University invited me to create their Fashion Design and Management program. It’s one of the first in the industry to include a whole subject of sustainability in its curriculum, and one of the first undergraduate programs in Latin America to take this approach.

When the program opened, I invited Juan, as well as Gloria Saldarriaga, Jorge Duque and Rocio Arias Hoffman. The idea was to not only look at fashion through the Colombian lens, but also through the lens of technology, which hadn’t been done before in the country.

Portraits by Andres Oyuela.

LATINNESS: Was this your start in sustainability?

CAROLINA: Yes. I said, “Wow, it’s amazing what we can accomplish with engineering.” The Universidad de los Andes then hired me, and I started teaching a class on sustainable fashion, where I worked with Professor Giovanna Danies, a biologist and phytopathologist (phytopathology studies plant diseases), in the Biodesign Challenge course. It was inspired by another course that’s given in New York every year.

It consists of an international contest in which Master’s degree students usually compete by presenting projects that can be conceptual, since they don’t need proof of concept supported by scientific literature. From there topics arise, such as new ways of creating energy, biomaterials, medical applications… there’s everything. The cool thing about that contest, and about this course itself, is that designers are participating, not engineers nor biologists.

Our students competed (they’ve done so since 2017). In 2018, Stella McCartney had a special challenge (there are brands or companies that create a specialized challenge in their field). At that time, she partnered with PETA to find an alternative to wool, which generates environmental impacts due to methane and animal abuse. There are only two places in the world— in New Zealand and Peru— with companies that certify they don’t shear.

Our students set out to find a solution and found that by using coconut and hemp fiber, and adding an enzyme found in milk, they achieved a morphology very similar to that of wool, even giving it softness because the two fibers are scratchy, like a sponge. The project was called Woocoa.

One of the things about biodesign is that living organisms must be used in the processes, either through synthetic biology or genetic engineering, such as fungi, the mycelium that’s so fashionable now. They applied the theme in their own way and won the contest. We went to the Stella McCartney headquarters in London, and it was very interesting to see the most quoted person in the world on the topic of sustainability, having difficulties in applying sustainability at such a high level.

At that time she was not with Kering and her team was very small. They told us, “This is very difficult because of the costs and the processes, which are incredible, but not massive; also, the market doesn’t accept… there are many things that don’t work.”

From then on, I got totally involved in biodesign and started working with Giovanna on different processes.

LATINNESS: What exactly is biodesign? What purpose does it serve?

CAROLINA: The Biodesign Challenge was born because its founder, who is a journalist (not a designer or a biologist), started writing articles about biotechnology and realized that there was a trend and that many people, in different places, were working with biology or with biological systems, who were not biologists. Something like a biology hacking.

So he created an open source laboratory in Brooklyn, which was one of the first to be founded in North America. From there he said, “How can we invite students and bring to life a platform that has much more open viability?” That was the seed.

Then there’s something called Nature Code Design, which started before biodesign. Designers have always looked to nature for inspiration. If you look at art deco or art nouveau, the designs are based on nature. The Bauhaus 1919, as well, since it’s about designing with the environment.

The difference is that biodesign welcomes the biological processes that are suddenly found in a scientific article, but that do not go beyond that. It’s about opening the imagination and saying, “If I take this bacterium, this E. Coli (they found it emits color), and apply it to a textile, what happens? It’s about taking scientific knowledge that scientists don’t take advantage of and using as a design tool. The designer assures “this is possible”, although the scientist affirms, “this is not possible”. It’s using your imagination to unite these two disciplines.

The term as such arose in 2016 from a book called Biodesign, by editor William Myers, from the Netherlands, and Paola Antonelli, curator at MoMA. William gathered all the projects that exist in the world, put them in that publication, and since then, they began talking about biodesign and the Biodesign Challenge.

What’s cool is that the designers or design students who participate are from fashion, graphic design, industrial design, everything. When they’re there, they realize, “Wow, I can work with mycelium and create things with it.”

LATINNESS: In addition to Woocoa, your students have accomplished several successful projects worldwide. Tell us about these.

CAROLINA: In 2019 our students won the overall challenge with a biotechnology that managed to refrigerate to four degrees Celsius, and we started a venture. We patented bionanotechnology, and the project, which is called Nano Freeze, is currently working.

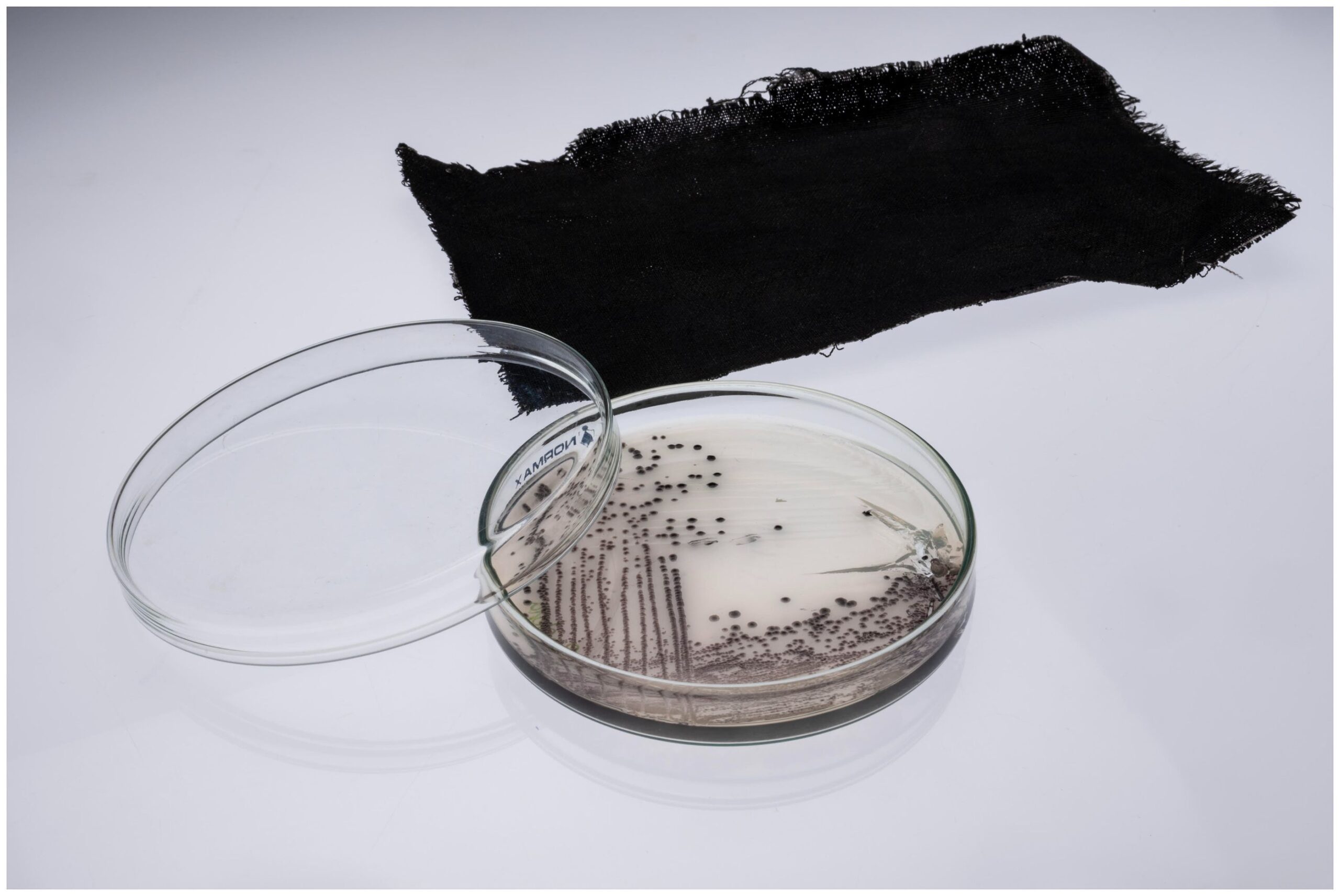

In 2020 we won the special challenge in the cosmetics genre with Mana, one of the largest cosmetics producers in the world. They make products for many firms, including Chanel. They were looking for alternatives to different types of cosmetics, and the students made a pigment from a fungus. They created an eyeshadow, and with that, they won.

LATINNESS: What is the commercialization like for these inventions?

CAROLINA: It’s very difficult because this starts in a laboratory. Then you have to make it scalable, and to make that possible, for example, in the case of Nano Freeze, you need investment. We were able to make it scalable because of investment and because of the team. Now, there are only two founders who lead it and one of them is tremendous: she’s a woman, young and pretty, so they don’t believe her. That’s an issue, because you talk to engineers and people who work in what’s called the cold chain, and they’re all older, white men, and well, these two Colombian girls show up and they don’t believe them.

So, it’s not just about economic issues. Also, they don’t accept things coming from Colombia because it’s not a benchmark for biotechnology, they don’t see it as a possibility.

However, the cool thing is that there are interdisciplinary teams— made up of designers, engineers, and biologists— that allow you to build groups that bet on the process and want to put time into it. In the specific case of Woocoa, we’ve been around a long time— from 2018 until now— and scaling is being able to search and find those actors who are willing to support you, so it’s not easy. You have to persevere and have faith.

In Colombia there are no venture capital hubs, like those that exist in the United States, especially in Boston, where there are a lot focused on biotechnology. In California and New York, as well.

What the Biodesign Challenge does give is visibility, and this in turn, allows one to start reaping fruits. Nano Freeze is an example of this.

LATINNESS: What would the route look like for an emerging Latin American brand that wants to transition from traditional materials to biodesign?

CAROLINA: We’re seeing it with projects that are already established companies. There’s one initiative that started at the hands of two engineers in Mexico called Desserto. It’s a vegan leather, although I prefer to call it bioleather because they biologically processed the residue of the cactus to develop a skin very similar to that of an animal. It’s a beautiful project.

An emerging designer can choose this leather and apply it to their processes. There are others who are embracing this hacking and doing things in their workshops, houses or their kitchens with mycelium, for example.

How? Well, there’s the fungus, right? This comes from the ground and has something called hyphae, which are like little hairs and these are known as mycelium. When that mycelium is put into a mold and it starts to grow, the idea is to stop the growth and make a type of material structure that’s very similar to styrofoam. There’s a company called Mylo, in California, that’s making leather from mycelium.

LATINNESS: I’ve seen several brands doing this. So they buy from them, basically?

CAROLINA: Exactly, but returning to the question, Bolt Threads, which is a company in the United States, started working with Stella McCartney to come up with a type of biological thread. They launched it with a piece by the designer in 2019, which was exhibited at MoMA.

It started at a very small level, but having that visibility with designers is what allows for the commercialization of these processes. This is, more or less, what we want to accomplish in Colombia— to work with emerging and established designers, and tell them, “take this and do what you want with it” so that we can gain visibility.

LATINNESS: Is there currently an organization or a directory that one, as a designer, can access to find these materials?

CAROLINA: There’s Material ConneXion, an organization that’s been around for 20 or 25 years and gives you access to a library of materials, though you have to pay. It’s not open source. It’s closed for universities and I imagine for companies, as well.

There’s another page, Materiom.org, created in Chile; It also has a bank of materials and recipes for designers and for those who want to make it at home. There’s another one in the Netherlands called Material District, where you can find information about materials. It’s super cool because they record everything that’s happening in architecture, in packaging, and one can access the information and directly contact the person or company. However, there’s no one specific place, everything is very spread out.

LATINNESS: How long does one of these materials last on average?

CAROLINA: What’s very fashionable is leather from mycelium or from some kind of biological process. The care is the same that you would give to a leather wallet or an accessory made of that material, because you don’t wash it. There’s a type of leather that’s also being used for shoes, even sports shoes, that offers the same durability as animal leather.

There’s a company that came out of the Biodesign Challenge, called Algiknit. It’s by a group of FIT students who created a type of thread made from microalgae. They won, and now the company is worth 70 million dollars. The founders are designer girls who were able to produce a proof of concept, meaning they’ve done tests, like in the Stella McCartney style, although they haven’t officially launched it yet. These are processes that take ten years.

LATINNESS: It took Lycra 12 years to hit the market in the fifties.

CAROLINA: Exactly. Everyone wants things now, but the industry as we know it is 100 years old. How are we going to do this in a minute? It can’t be done.

LATINNESS: You and your team published an article about a development in the use of cannabis sativa as a textile application in the Journal of Natural Fibers.

CAROLINA: Well, that development stems from Woocoa, in 2018. We started using a type of extraction. A friend sent us some sticks of marijuana, and told me, “do something with this because I don’t know how much I can do.” He’d always dreamed of creating some type of fiber from the sticks.

LATINNESS: Is there a difference between hemp and marijuana?

CAROLINA: They always get confused. Hemp is a plant that grows about five meters while marijuana reaches ninety centimeters or about one meter. So the first one is more interesting because it’s much longer, right? The countries that produce it are Canada and China.

It’s also important to mention that the THC in marijuana comes from the flower, while in hemp everything is used and the stick doesn’t have the THC that marijuana possesses– it has like 0.3, while marijuana has like 30. Something like that. So, there’s essentially no presence of the cannabinoid and, therefore, it’s not psychoactive.

The difference with what we’re doing is that we use the residue– we don’t plant new hemp trees. We only take advantage of a residue that, in general, is burned or thrown away, so has no purpose or use.

Marijuana grows very very fast, because it’s a weed. Usually they take the plant, use it to make CBD, use the oil, and the rest is thrown away, but what we did was extract the fiber. This process produced a result very similar to what had happened with the coconut and the enzyme with Woocoa.

I sent it to Juan at Cornell because they have crazy machines there. He did a study and said, “Wow, here’s an opportunity. The morphology of this fiber is very similar to what you had before. Let’s see how we can get this out and write a paper.” We carried out the entire process and managed to have very small proofs of concept, but we produced a fiber that could be applied to a textile. It’s really circular, because it comes from a residue. If you haven’t done any chemical processes, you can degrade.

This is a great opportunity for Colombia because there’s now a regulation to use hemp or marijuana derivatives. Before only the second was possible. It’s incredible!

LATINNESS: What do you think our closets will look like in fifty years?

CAROLINA: Wow, they discussed something like that in The Business of Fashion. Someone tweeted: “We should buy less and be more sustainable.” And the whole internet attacked him: “How? That’s only for people who have the money to do it.”

In my case, I’ve been buying second-hand and vintage clothes since I lived in New York in 1994 because I had no money. I always do it. I buy and support Colombian designers. I think it’s important to support the local designer and acquire only what’s necessary. Now I’m trying not to buy leather (shoes, boots), but it’s very difficult to find something good.

LATINNESS: Are bioleathers more expensive?

CAROLINA: Exactly. So it’s up to you to think about it. I think that in fifty years we’ll have textiles, as Juan Hinestroza says in his presentation on nanostructuring. That’s what we’re doing with another project: giving textiles a purpose. In other words, that it cools and heats, can regulate your vital signs, etcetera, so that it’s not only something aesthetic, but also part of your life. That it generates health– even a smell. I think that’s what’s going to happen– it’s going to be the next textile revolution.

LATINNESS: In gastronomy it’s similar, in fact.

CAROLINA: Yes. We’re behind the gastronomic revolution, which began with the bougie in 2004 and the micro kitchen. I think that’s the way. In 2011, Steve Jobs said, “The next industrial revolution is going to be that of science with technology.”

LATINNESS: Apart from teaching, what projects are you developing right now?

CAROLINA: Currently, I’m a mentor and advisor to Spora Studio, a venture where materials and products, such as packaging, are developed from mycelium (mushrooms).

Also, I’m a professor and academic in Fashion and Strategic Design at Parsons School of Design.

LATINNESS: Perhaps one of the biggest problems with the fashion industry is the massive production and the constant purchase and disposal of clothing. If biodesign becomes massive, do you think the solution will become a problem again?

CAROLINA: Sure, yes, absolutely. Anything massive is not sustainable.

LATINNESS: It’s more about individual control.

CAROLINA: Of course, responsible consumption. My teachers in Finland, who are important people in the world of design, would buy a jacket or a coat, and I’d always see them wearing the same thing.

LATINNESS: Just like Steve Jobs, in a way.

CAROLINA: Yes, exactly. It’s that we don’t need everything we buy. If you take the biomaterials and massify them, you have the same problem. I think it’s an alternative– I don’t like to say it’s a solution or a replacement. It’s just an alternative.

Images courtesy of Carolina Obregón.