COFFE WITH

ANDREA PEÑA: “I’M PART OF A LINEAGE OF ARTISTS CARVING SPACE FOR OUR COMMUNITIES”

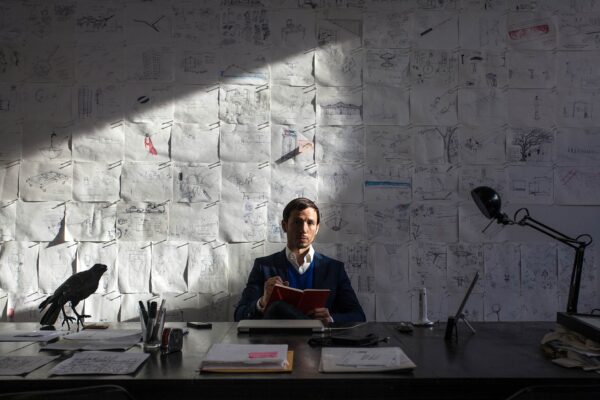

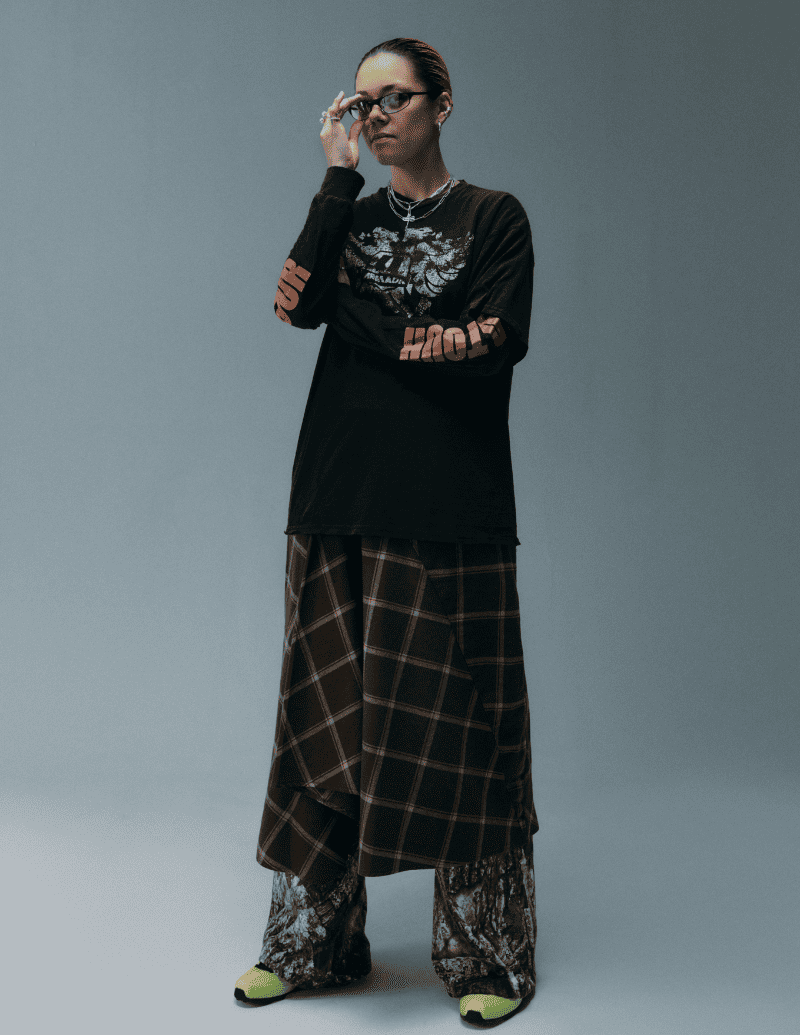

Name: Andrea Peña

Profession: Artist

Nationality: Colombian

Zodiac sing: Sagittarius

Instagram: @andreapena__

Congratulations on receiving this year’s NEXT Prize by CHANEL, a program that recognizes contemporary artists who are redefining their disciplines. What does it mean to you to be part of such an initiative?

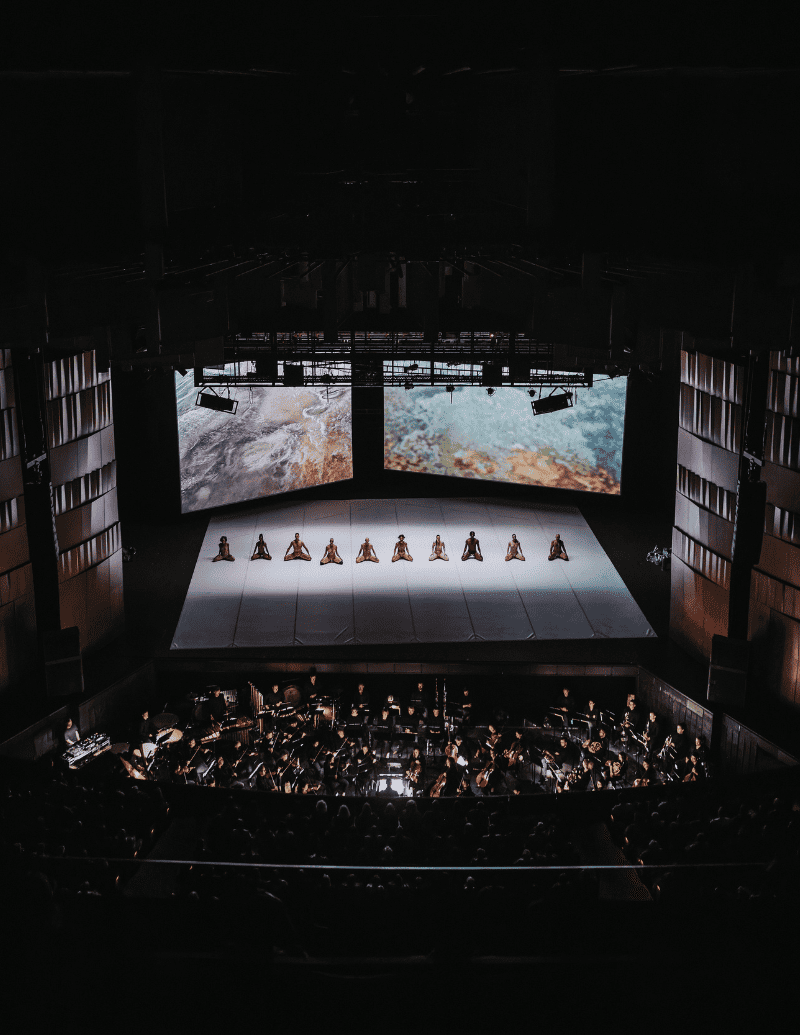

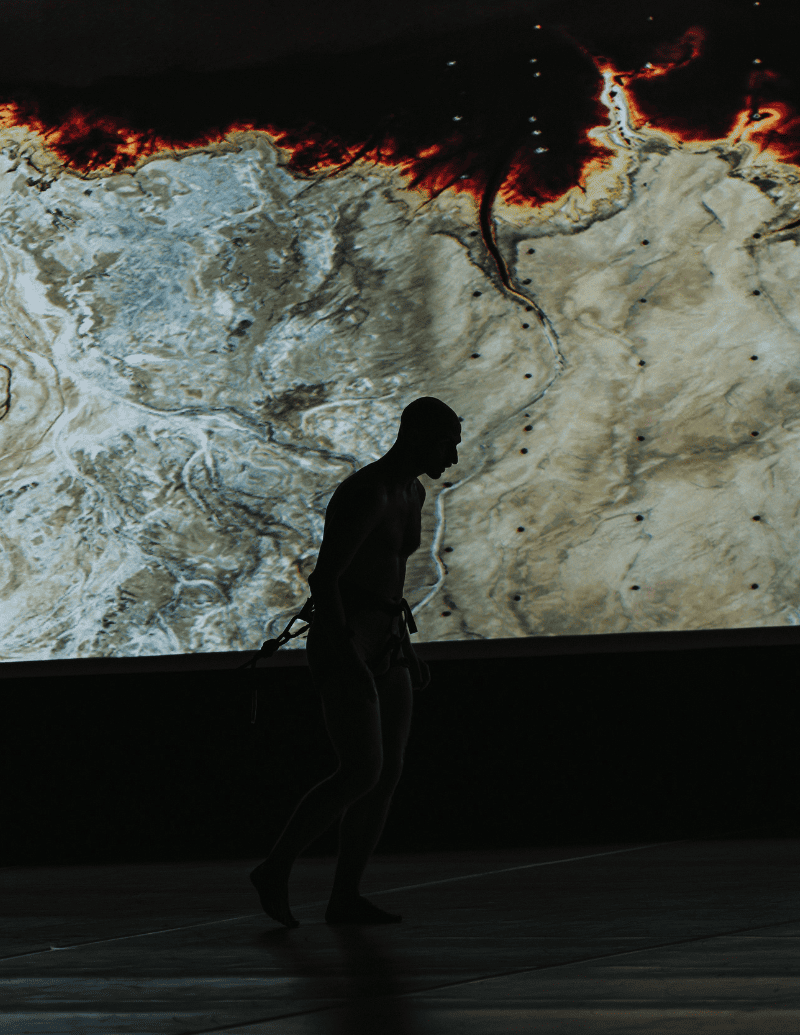

Thank you! This moment aligns with questions I’ve been pursuing for years, questions that have been at the center of my journey as an artist: how to redefine a discipline by honoring and centering perspectives from the global south, by speaking from queer and fluid values, and insisting on non-Eurocentric views. This prize recognizes that these perspectives aren’t peripheral, they are part of the past, present, and future of our collective imagination.

At LATINNESS, our mission is to inspire the next generation of Latin creatives. Having been born in Bogotá, how did your journey into choreography begin, and what led you to pursue a creative career in dance?

I learned from a very young age how bodies adapt inside systems not built for them, immigrating from Bogotá, Colombia to Vancouver, Canada. These invisible languages of adaptation, displacement and hybridity were sensibilities seeded early in my childhood. Questions of identity, expression, belonging began marinating from a young age. Questions that today shape not only the work I make but the impetus behind why I started to create work at 23. Choreography purely came from finding a medium where the body was capable of expressing in complex ways layers of its own individuality and breaking away from the systems that structure or constrict our everyday lives. Design on the other hand, equally central to my practice, became the medium through which I could transform the stage itself, creating spaces that reflected the cosmology of home.

This deeply human, raw, and punk expression, in bodies and in materials—that’s the Bogotá I carry in my heart. The resilience and warmth—that’s mi Colombia.

What challenges, if any, did you face early on?

I wish I could say I ‘faced’ challenges in the past tense, but I still face them. One would imagine that through the evolution of a career, challenges would dissolve, yet bringing a Latinx perspective to the world of dance is still an ongoing challenge.

Introducing our perspectives, philosophies, and non-Western symbolism comes with a journey of insistence, of perseverance, of literally calling my ancestors to embark on the journey with me. I know that facing these challenges doesn’t only open doors in my path, it opens doors for future generations of Latin artists. I’m part of a lineage of artists carving space for our communities. Bad Bunny has done this incredibly for Latinos in music. Dance, I’ll quietly admit, is lagging behind.

You made a powerful transition from Colombia to Canada, becoming a dancer with Les Ballets Jazz de Montréal and Ballet BC. How did that journey unfold, and what concrete steps did you take to access those opportunities as a young dancer from Colombia?

My parents immigrated to Vancouver when I was 13, so I had already been in Vancouver for a few years. These opportunities to work with these companies did not come easy—they came after carving my voice as a performer and trusting in what I had to offer. For example, I remember being told at 16 that I moved like a ‘bull in a china shop.’ At the time this was a devastating comment to receive as a young dancer. Today I understand that energy as my roots, my power, the ancestral fire that guides my practice.

I must admit that even in those companies, I felt out of place, like the values with which I wanted to create work were in conflict with how large companies were being managed at the time. And this was one of the big drivers for me to create my own company. To put humans before the craft.

In 2014, you founded your own dance company, bringing together artists from diverse backgrounds. What qualities do you value most in a young dancer today?

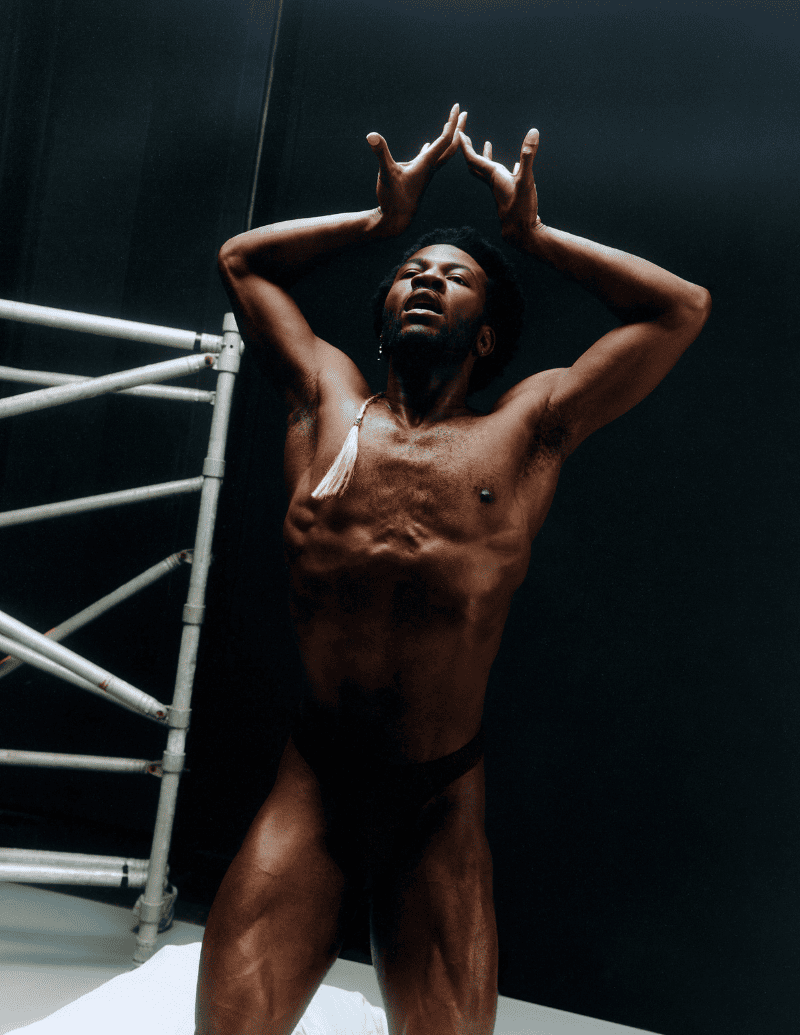

For me, building AP&A was about building a family of artists before a company. It was about gathering like-minded individuals who shared a sense of critical agency, reflection on our craft, and wanted to explore deeper places in their own artistry. It was less about ‘finding dancers’ and more about connecting with the individual as an artist and understanding their critical thinking and own human quirks. It was about imagining a company that would create conditions for the futuring of our practice— a place of pluriversality over sameness. Our artists come from Brazil, Lebanon, Mayotte, Vietnam, Australia, Italy and across North America—including African American, First Nations, Acadian and Canadian backgrounds.

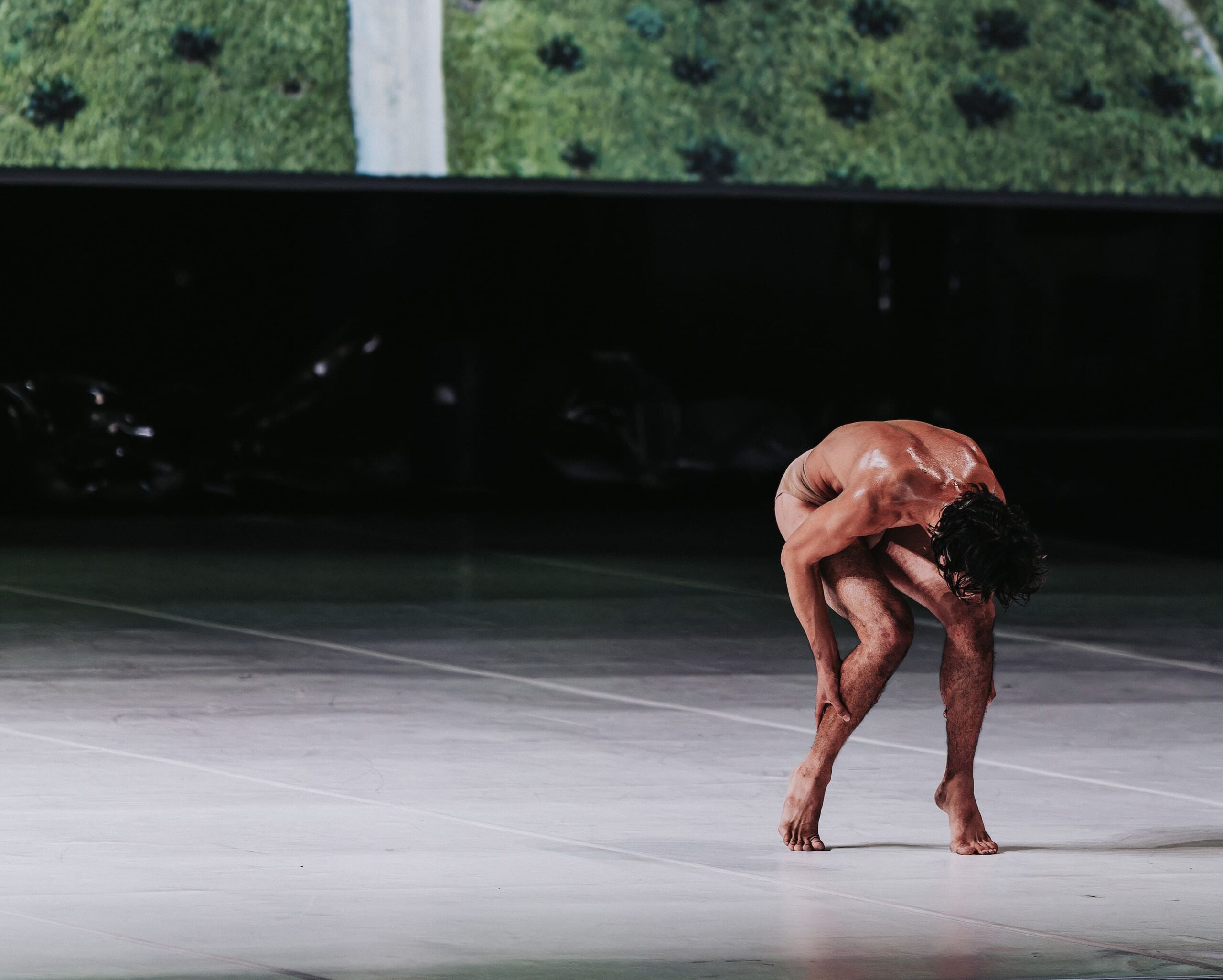

What I look for in a collaborator and performer is really their connection to their own artistic and personal voice. Their capacity to engage with agency and with decision-making in real time. The works we create are highly rigorous and athletic, most of my dancers strength training outside of dance, yet at the same time the work is highly conceptual. So we need to collectively be able to discuss, to bring our diverse points of view forward, to propose, to fail, and to sit with ambiguity and not knowing. Trusting that the work creates itself through the in-between layers of a process.

One of the most unique and compelling aspects of the CHANEL NEXT Prize is its unrestricted funding, which allows recipients to thrive on their own terms. How important is complete creative freedom to you? At the same time, friction and limitations often lead to more interesting work—how do you navigate that balance in your practice?

I don’t think we ever create in complete creative freedom — yet I think creative liberty is really important. But inside that liberty our job is to find the structure, the walls or parameters of the work, to understand its limitations and its boundaries. Friction, as you mention, is highly lucrative for me. I adore complexity, the undefined, the raw, the unfinished, as it has much to teach us. Similar to Latin America, which carries this same raw, unfinished complexity.

These are the subtle intelligences of the global south, this is our fuel as artists born from these histories. So in my work I navigate the ambiguity, I allow not knowing, I make space for failure, for experimentation without direction, trusting that the direction will find its path.

What role does mentorship play in your industry, and how has it shaped your own path?

The choreographic practice is, honestly, highly individualistic. Many choreographers fear having other choreographers see their work in progress, yet I think the new generation is shifting this. In my case I have been fortunate enough to have a support group of female choreographers in Montreal from across different ages, with whom we share our struggles, our successes, our questions and artistic reflections. We created this space together about 6-7 years ago, which is very rare in the arts world, and it has been incredibly precious, offering support, intergenerational mentorship, and a community that cheers for one another instead of being in competition.

For young dancers in Latin America who dream of joining international companies, how can they realistically seek out and access these kinds of opportunities today?

I think more than ever these opportunities are more accessible now than when I started, whether that’s through social media, instagram, video auditions– the scouting landscape has expanded significantly. Also building relationships online is part of the language of our times. Artists contact my team regularly or write to me on socials, introducing me to their work. It’s a great way to connect with individuals outside of our immediate sphere.

The industry itself is also shifting. Many companies, and artistic directors are looking for artists with unique voices, it’s no longer about fitting the ideal mould of a “contemporary dancer” rather showing up with the vast array of things that make an artist authentically them. This truly does get noticed, and our medium is evolving, making much more space for individual or cultural specificity.

What advice would you give to Latin American creatives who aspire to build an international career?

I’m moved to see more Latin creatives claiming space in the global arts world. We carry richness that makes us unique, values, traditions, philosophies, ways of being that aren’t found everywhere. Those voices are needed now more than ever, no matter what medium you work in.

Here’s what I’d say: No one will believe in your work more than you do. It takes relentless hustling, and unwavering belief in what you bring. There will be moments when you feel like a “bull in a china shop,” embrace that energy, it’s your power, what makes us authentically Latin American is our strength, not something to minimize. What felt like obstacles in my journey, my latinness, my queerness, my non-European perspective, became the very fuel for my work. The world is finally ready to make space for us, but we have to insist on it.

And last, build relationships. Reach out to artists whose work moves you, show up with generosity, and find your people. We need each other to sustain this work for the long haul.

Are there any Latin American dancers you particularly admire or feel inspired by? And closer to home, is there a dancer or troupe in Colombia whose work you deeply admire or feel connected to?

Honestly, I draw fuel from across disciplines more than from dance alone. But seeing Colombian Afro-dance company SANKOFA DANZAFRO in Ontario while we were both on tour was profound—it brought me to tears. Their work carries the ancestral wisdom and cultural specificity that reminds me why representation in dance matters. I’m also inspired by Colombian visual artists like Delcy Morelos and more emergent artist Laura Campaz, who navigate similar questions of identity and place.

How would you define Latinness, and what do you love most about your culture?

For me, latinness is community and heart, it’s the spirit I feel our culture carries. We are people with incredibly resilient, humble, vulnerable, and joyous spirits. There’s ancestral wisdom that runs in our blood, a knowledge about the subtle richness of connecting as people on this earth. It’s in how we gather, how we hold each other through struggle, how we find joy even in the raw and unfinished.

When you close your eyes and think of your native country, Colombia, what song comes to mind?

My grandfather is from Boyacá, so when I close my eyes, I hear the Andean flute (or zampoña /quena) as if it’s floating through la Cordillera de los Andes. It’s not a specific song but that ancestral sound, like in bambuco, this music of the mountains that shaped me.