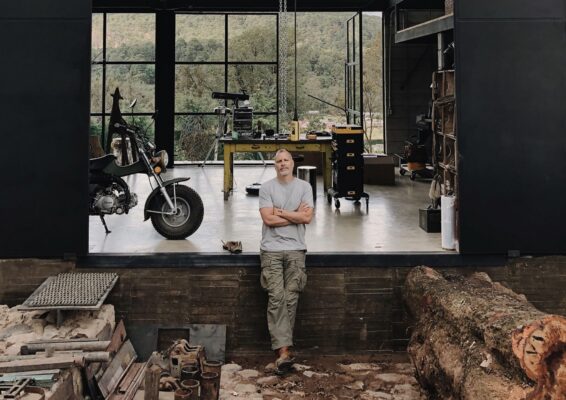

Sebastian Errazuriz by Ari Espay.

COFFEE WITH

SEBASTIAN ERRAZURIZ: “PEOPLE CAN EITHER LIKE ME OR NOT, BUT AT LEAST THEY KNOW I’M HONEST”

Name: Sebastian Errazuriz

Profession: Creative

Nationality: Chilean

Zodiac sign: Cancer

Instagram: @sebastianstudio

LATINNESS: Sebastian, you are a citizen of the world. You were born in Chile, grew up in London and studied in New York. Is that correct?

SEBASTIAN: Exactly. I studied for a while in Chile. Then, at 18, I moved to the United States, specifically to New York.

LATINNESS: And how did you discover the art world?

SEBASTIAN: My father is a doctor of education through art meaning he is dedicated to educating every child in Chile in art from kindergarten to the age of 18. I learned through the art program he designed, and I was the first one he trained, kind of like a lab rat.

I’m like one of those kids you see on Netflix, whose parents are obsessed with some sport and train their kids to be golfers or football players. In my case, my father became obsessed with me becoming an artist, and it just so happened that I found it easy and enjoyed it.

LATINNESS: Like a King Richard, but the art version.

SEBASTIAN: A bit. The difference is that in sports, everything is measurable, and in art, it’s not. However, having a father like Will Smith was surely entertaining because he was in the maze. What King Richard did was go out and seek opportunities.

In my case, my father was extremely strict.. Nothing was ever good enough for him. My younger brother was the only one who didn’t turn out artistic, but he had the best grades in science, mathematics and everything else. My father would scold him. He’d look at his grades and say, “José Pablo, how can this be? You have a five in art; this is terrible… you’re going to be punished.” I’d step in, saying, “Hey, Dad. Look at the rest of his grades; he’s the top student in everything else. He just doesn’t like art, and that’s okay.” He was like a father getting upset with his child for not doing well in math or science, which is the traditional way, but reversed.

LATINNESS: Today, I was listening to a podcast by Scott Galloway, in which he talked about the importance of living in one of the 20 mega-cities to enrich yourself with these kinds of opportunities. Do you feel that growing up in London was valuable for you as a child?

SEBASTIAN: In my very early years? Yes. My childhood unfolded in London. Those formative years when you are exposed to a wide variety of cultures, religions, it’s something much more interesting, especially in a time when there was no internet, nor access to information and culture depended on your environment.

Having a mother who was a preschool teacher, somewhat of a psychologist, and a father fully focused on the arts, taking us to museums every weekend, and having friends from different backgrounds (Indian, Muslim, German…) helped a lot.

Later, when I attended university in Chile, a country of 17 or 18 million inhabitants, isolated, classist, racist, homophobic, very conservative, and extremely religious, it was a different story.

Religion can have a very positive aspect, but also very negative ones when it’s very structural, especially in creative fields. I think that made it more challenging– trying to carve out a space in a career in a country where there was almost no market, and every idea was diminished. Who knows what would have happened if I had been in New York or London during those years!

LATINNESS: Of course,a bit of an oddity, in a way. Yet Chile had this emerging creative environment that we’ve seen in some movies.

SEBASTIAN: I don’t think there was an emerging creative movement in Chile. On the contrary, I believe it had much less than other countries.

LATINNESS: In that case, sometimes challenges help create good art. Do you think the fact that what you were looking for didn’t exist in Chile fueled the need to explore some themes that in London might have been more common or that you wouldn’t have questioned? Sometimes, those kinds of situations add a bit of depth to art, don’t they?

SEBASTIAN: It’s a good point. I don’t know, Kelly. On one hand, there are many studies showing that some successful people reach that point through a mix of knowing they have the support of one of their parents while simultaneously seeking paternal approval and facing a certain degree of tension or problems.

I had that. On one side, parents who loved me, but on the other, nothing was ever enough for them. There were also limited resources and opportunities; certain things were not there. As a child, I had hunger, anger and desperation, but at the same time, a lot of affection.

If you look at examples from Latin American countries, especially when comparing arts, design, advertising and fashion, very few have been able to break into international culture. This is partially related to the size of the local market, right? If Mexico had had a giant market 20 years ago, perhaps it would be more influential globally.

However, most of what we see at this moment is art or creativity that is still considered almost indigenous. It almost fulfills the quota of inclusion and diversity that we aim to generate, not because it is globally attractive or meritocratic.

‘Second Nature’ designed in 2017 for Audemars Piguet’s Art Basel Collectors Lounge, (Hong Kong, Basel, Miami).

LATINNESS: In general, Miami is a hub where artists, galleries from Latin America, or individuals like you end up connecting with the outside world, right?

SEBASTIAN: Of course. However, I believe that European collectors, and even Americans, tend to pay less attention to Latin galleries or artists because they are still seen as a kind of curiosity. A bit like how they view the trendy African artist. That explains why prices are rising, and there’s an area of the market that can keep going up; for them, it’s acceptable to incorporate a greater variety of work into their collection.

However, they often don’t tend to take them as seriously as they do with artists from Chicago, New York, or Los Angeles, or those from Paris or London.

Maybe for that reason, I never wanted to present myself as a Latin artist. On one hand, perhaps I don’t seem like one that much, and the somewhat British accent wouldn’t have played well. But fundamentally, I never wanted to be part of the sale of Latin American Art at Sotheby’s or Christie’s. My idea was to be part of the sale of Contemporary Art. The same goes for Design. It’s like being an athlete who doesn’t want to go to the Pan American Games. I wanted to participate in the Olympics.

LATINNESS: Of course, that your art is recognized on its own merit.

SEBASTIAN: I don’t want my work to be known for being Latin. I want it to connect with people on a global and timeless level, even if that takes more time.

I feel the same way about art and design… I’m not willing to give up one for the other, which is a question I’m always asked: “Are you an artist or a designer?” And I respond: “That would be like questioning me: Do you speak English or Spanish?” They are different languages, with different cultures, codes, structures, but fundamentally, they are languages. And as long as one speaks them fluently, what matters is what one can say.

I’m not just an English speaker or a Spanish speaker, do you understand? Therefore, I can be a designer-artist and everything in between. Also, when you handle a couple of languages or more, you understand the construction of language, common elements, and even borrow words that only exist in one language or incorporate nods, phrases, and certain idioms to enrich and make communication even more precise.

I’ve been into that. And I add one more curveball, as the Americans would say. I haven’t wanted to dedicate myself to a style, a single theme of work, or a single medium. All of those seem like arbitrary limitations that we embrace because it’s incredibly difficult to focus on so many different areas, but not because it can’t be done.

Since I was raised in the arts, for me, those who do the same thing over and over again seem like a cop-out. Mediocrity. And I always give the example of the one-hit wonder in music.

LATINNESS: It is a topic we discuss with many people we interview. The fact of simply being creative.

SEBASTIAN: That singer who releases only one song, or one with two variations of it, which is on the summer playlist, and if we played it now, the three of us would be dancing, we understand that it’s not so serious or not so talented because they weren’t able to reinvent themselves, to keep exploring, to reconnect.

That also happens in the arts– the vast majority of top sellers are one-hit wonders. That’s why I avoid being the artist of a cultural area, a discipline, a style, or a particular body of work. Therefore, my commitment is longer, and I need much more time to prove that I deserve a space because I’m trying to do it simultaneously in different areas.

However, I hope that as the bodies of work become clearer, the impact I’ll have will be different. The knowledge of different areas and languages allows the contribution to be even richer with more layers and levels of awareness.

Faena Maze, Art Basel Miami Beach, 2023.

Winged Victory Desk, 2022.

LATINNESS: How do you perceive the evolution of your work from more conceptual projects? From American Kills; then, taxidermy; later, the moving furniture, until what you do now… How do you perceive people’s appreciation evolving? Do they understand all these areas a bit?

SEBASTIAN: I think several things are happening. For example, Art Basel is now in Paris, but essentially, for the past 20 years, it has always been Art Basel Miami Beach. Later, Hong Kong was added. We could say that Art Basel is the Olympics of the Arts. And while Switzerland was considered the serious one in the past due to the size of the U.S. market, for about the last five years, it has been very clear that the most important fair is in the United States.

And I’m not only talking about the main fair. There are also secondary fairs and pop-up events. As an example, what Faena does annually. Because of its weight as the most awarded hotel every year, the attention it garners, and because it practically has a spot on the calendar, it’s almost like an Olympic event. That they have managed to make it the most photographed and discussed of Art Basel is very positive to me because it went from being a kind of writer’s writer or drummer’s drummer.

For now, I continue as the artist and designer in a kind of half-underground cult. I think that has been very good.

Another thing that is starting to happen is that there are themes, such as artificial intelligence, for example, and the impact of technology, that I have been dealing with for ten years, like the sculpture that was shown in the lobby of Faena in 2016. No one understood that piece.

Particularly, even though tech companies were already reaching levels of money reserves at that time much higher than in small countries, CEOs didn’t have that much influence. It still wasn’t understood that they could be more important than a president.

Today, that is starting to become clear; much more so since we understand that they can disconnect satellites and cut off communications for two nations at war.

We move to another level of connection. Do you understand? The moment when Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post, and at the same time, has more than 50% of online sales in the United States is another level of influence.

LATINNESS: A valid point.

SEBASTIAN: I always gave the same example: if we were on a vacation trip to the Middle East, to a risky country, or to certain areas in Africa, and rebels kidnapped us, demanding a certain amount for our release, which president would have a better chance of negotiating our freedom? The one from Chile? Portugal? Panama?

On the other hand, if someone worked for one of these big companies like Facebook, Tesla, or Amazon, it might be more advantageous than being a citizen of Portugal, Ireland, Chile, or Panama. Because perhaps the rebels would respond much faster to a call from Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk, right?

There are changes that the public is only just starting to understand. Bodies of work that have been around for a long time but now have another level of respect. There’s more credibility and a greater benefit of the doubt, like, okay, you’ve got my attention, show me a bit more. That didn’t happen before.

I think these balls are starting to drop. We’re approaching a tipping point.

LATINNESS: Considering your father’s high standards, how do you define success in the type of art you’re creating long term? Because in our eyes, you’re a successful artist, but from what I understand, perhaps you feel you haven’t achieved the success you’re seeking.

SEBASTIAN: Me? Far from it. Look, when I was a kid, my allowance depended on creating the slides for my father’s university classes. I would sit with lists of slides, look at them, and had to write information about each painting on the edge.

As a child, when I had a general knowledge of art, by far the most important artist was always Leonardo da Vinci. Therefore, for me, it’s always been about being a small percentage of him. It was much better to aim for 15% of Leonardo da Vinci than to strive for 40% of Picasso or 60% of Jeff Koons.

LATINNESS: Of course, a Renaissance man.

SEBASTIAN: For me, that was very clear. ]Leonardo is a guy who also embraced this more Renaissance idea of the artist because he combined engineering with science, art, and architecture. So, my goal has always been to be the best I can be. And that’s a battle against myself. I hope that at 80, they ask me: How did it go? Right now, I’m barely halfway there.

LATINNESS: Fascinating. Always reach for the stars.

SEBASTIAN: It’s incredible that there are so many incongruities and discrepancies in the arts compared to other areas. If a child or a young person says they want to be the best artist, they would be told that it’s pretentious.

LATINNESS: Absolutely.

SEBASTIAN: And the thing is, people believe that art is in the eye of the beholder. That all artists have a space. But if that same child says, “I want to be the best basketball player or the best soccer player,” the world celebrates them, buys them balls, and enrolls them in a course.

If an artist works 14 hours a day, everyone says they’re obsessed and a workaholic, that they need to go smoke a joint and find inspiration in the hills. But if a basketball player is shooting baskets from 6 in the morning, practicing over and over, that’s what is expected of them.

Hence, there is so much disconnect in how we treat the arts, because I believe that the majority of people, even collectors, see them as something curious, cute, almost like a craft. They don’t take them as seriously. I think these are system errors and reflections of bureaucracy. And I feel it’s vital to return to competitiveness, excellence, and demand, especially in a time when artificial intelligence is becoming so prevalent in all areas.

If we don’t do this now, we’ll be in trouble for the next ten years. Because artists are easier to copy these days since they repeat themselves. That’s why you hear people say, “Make me a piece in the style of Jeff Koons or Kusama.” They repeat themselves to the point that instead of being artists, they become designers for luxury brands.

Today, between a Jeff Koons, a Daniel Arsham, or a Louis Vuitton, there’s not much difference. One puts LV on everything, and the other puts crystal pieces on everything. It’s the same nonsense that doesn’t deserve to be considered a reflection of our existential search or how difficult it is to explain human existence. I don’t know. Both are luxury brands, nothing more.

‘Lightning Strike’ light installation, 2023.

‘Fallen Monument’ bench, 2022.

LATINNESS: You’re very active on social media. In fact, we’ve been following you for several years, and I was glad to hear that you were the most photographed at Art Basel, because that probably helped with the algorithm you complain about so much. What do you consider the role of an artist in the era of social media?

SEBASTIAN: I had to participate in a talk about the future of creativity in the era of technology. It was the only event I did during Art Basel week. The other panelists were also creatives; some were designers. The other artists laughed at me because with every post, they saw that I wanted to stir the pot.. They accused me of being overly honest and getting involved in problems I shouldn’t.

I hope that also has value in the long run. I feel that people can either like me or not, but at least they know I’m honest. And I think that, as society changes rapidly due to technology and other issues, and we need opinions from people who suggest what to do or where to go, or what options to try, we’ll need more voices that we can believe in, that are honest and well-intentioned.

I’ve always tried to be honest. Of course, I try to “market” myself a bit, like everyone, and be clever about certain things, but fundamentally, I talk about the topics I feel I need to discuss. I post a wide variety of things that interest me. I can be playful or serious, but in the long run, I feel that over time, a certain level of respect has been generated. People may like it or not, like me or not, but still, I think many think, “This guy works hard and is honest.”

In the long term, as things become more saturated, this can be good human capital to rely on, to be able to help more, to make a greater contribution.

LATINNESS: The good thing about people like you is that they generate important conversations. Regardless of whether people like it or not, at least they’re talking about it, right?

SEBASTIAN: When you’re younger, you’re more anxious and have more to prove. I’m like a battery, but I think over time, you become more moderate. And hopefully, over time, I’ll learn to be a bit wiser, a bit softer, a bit… Avoiding confrontations, but with the same level of strength, honesty, and the ability to express what I think, hopefully with the corresponding arguments and everything. I hope time plays in my favor.

LATINNESS: Since you’re a disciple of creativity, and we have young creatives following us, what tips or practices do you recommend to foster creativity?

SEBASTIAN: Let me see, many. The first one: there are the typical cliché phrases attributed to Picasso or others, like 99% perspiration, 1% inspiration; that’s 100% real. The most successful artists I know are also the hardest workers.

The second one: in this era, it’s essential to find a way to disconnect from the phone because with the little attention we get, creating windows of space for ideas to emerge becomes very difficult if it’s very short. In my case, I’ve tried everything, from buying the container with a timer that blocks the phone, to giving it to my girlfriend and having her set another password. What usually works best for me, and is much simpler, is music. Listening to music llively enough that it stimulates me in such a way that I don’t want to look at the phone and allows me to be so immersed that I go on for a while.

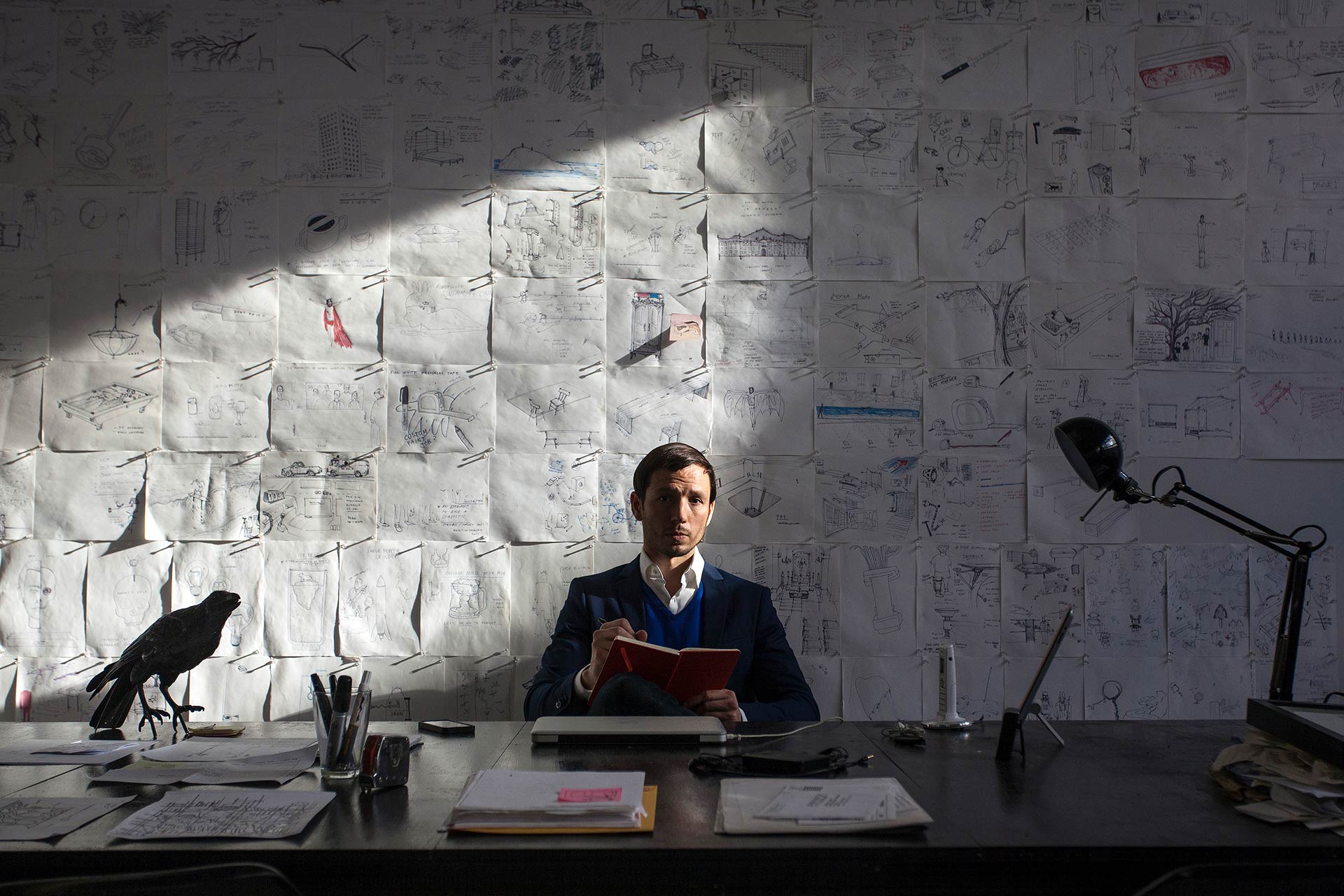

Another recommendation is to find a ritual or mantra similar to what those who meditate use. A kind of “Om” that allows you to focus on breathing. I tap the table, as if marking a pulse. So, I usually have paper and a pencil, play very loud music, and tap the table. Although it sounds odd, it’s almost a matter of sexual tension because you build up a certain crescendo of strength; in my case, I force myself not to think, not to think, not to think, not to think, generate energy, and ideas start to come to me.

LATINNESS: Very interesting and so simple…

SEBASTIAN: It’s like being the medium in a movie who has her crystal ball and says, “I have an idea.” That’s how I start to come up with small ideas, and I scribble as fast as I can. This process is almost like a science fiction movie where a window to another reality opens, and generally, for some reason, it only lasts for a certain amount of time, and then it closes.

So, I have a window of time in which I try to come up with ideas that, I believe, come from the unconscious because they are very strange associations that don’t make much sense. Then, when I finish, somewhat exhausted, I start looking with the conscious mind at everything I did, and although the vast majority is useless, occasionally there are certain glimpses. Why do I like this? Because it’s interesting to see that some of those ideas are almost like a gift, and you are the first to receive it, enjoy it, and savor it because I think you can identify a rational association from the unconscious.

My last piece of advice would be to wait. We always assume that the idea we have at the moment is good. I believe it’s better to go on enough dates before committing to someone– it’s the same with ideas. If you’re going to invest time, energy and reputation in them and present them to your people, they have to be good. And for that to happen, it’s preferable to make them wait. You can’t marry the first idea immediately.

To achieve this, there are different systems. It helps me to have the ideas somewhere– stuck on a wall– because if I put them on a sheet or in a notebook, I won’t look at them again. On the other hand, if I see them stuck, visible, between going to the bathroom, coming back from buying something, or going somewhere, I run into them, and if it was mediocre or lacked something, I find the piece that fits to make it worthwhile.

LATINNESS: Visualization!

SEBASTIAN: That’s why my advice is for everyone to find their system. I believe that creativity is a science just like any other, which we have misunderstood or not practiced. We have been very irresponsible with it by wanting to attribute democratic qualities to it. By this, I mean that when certain ultraliberal values are applied, starting from goodness, inclusion, the ability to help everyone, they generally decrease the levels of demand and responsibility. This is how entire categories decrease in quality, and we forget what effort is. We start to lose certain values necessary to truly reach a greater good. I believe that art is not democratic because it is a language.

Therefore, if someone hands me a Shakespearean work in Mandarin Chinese, I cannot read it because I don’t have the codes to do so. In contemporary art, we all react similarly to certain colors, certain drawings, certain images, but fundamentally, it’s a language. I relate it, for example, to the experience of going to Paris, and even if you have a more or less decent French, they look at you poorly when you speak it with them. Right? Because no matter how good your accent is, if it’s not perfect and native, you’re not from there. The same thing happens in the arts. In the arts, there are the same levels of status and standards, and they are languages, they are codes. It doesn’t mean that one language is necessarily better than the other or that one can determine who owns the language. Languages change, just like words and idioms, but language is not democratic. Language requires that we learn to speak it if we are going to participate in it, even if it is to change the language itself.

Images courtesy of Sebastian Errazuriz Studio.