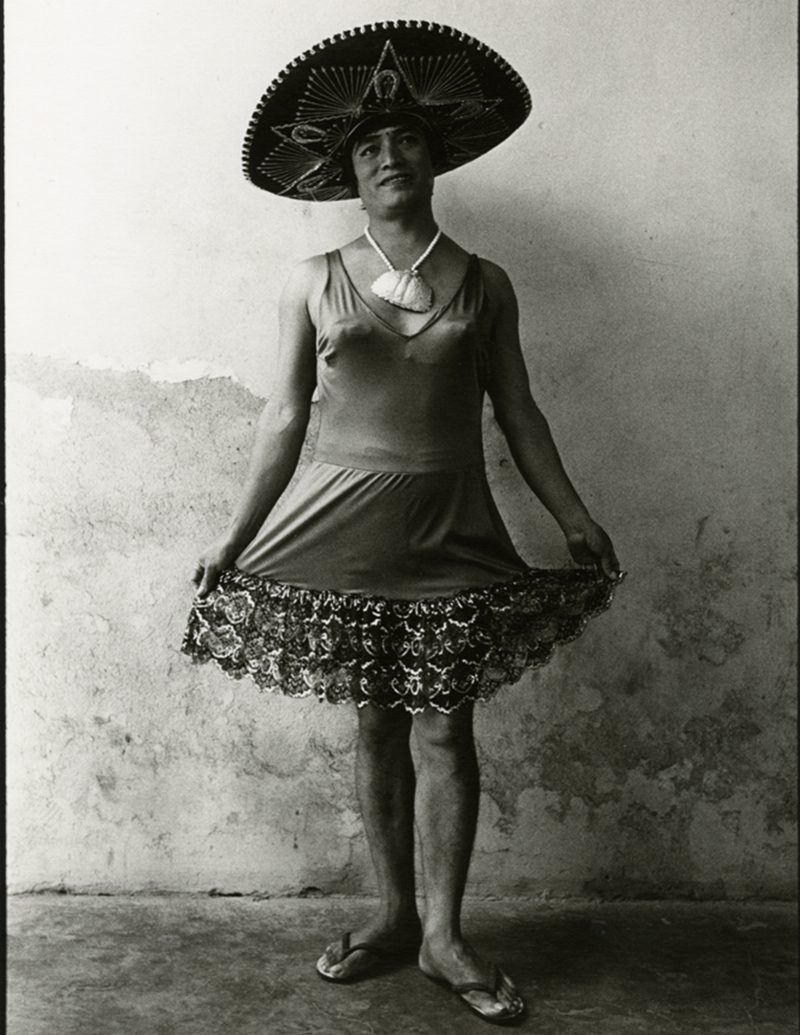

Angel Woman, Sonora Desert, Mexico, 1979.

COFFEE WITH

GRACIELA ITURBIDE: “THROUGH THE CAMERA YOU CAN DISCOVER THE WORLD, SOCIETY AND YOURSELF”

Name: Graciela Iturbide

Profession: Photographer

Nationality: Mexican

Zodiac sign: Taurus

Instagram: @gracielaiturbide

From February 12 to May 29, 2022, the Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art presented Heliotrope 37, the first major exhibition devoted to Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide in France, spanning works from the 1970s to the present. Iturbide has been awarded with the W. Eugene Smith Award in 1987 and the Hasselblad Award in 2008 for her photographic work. In connection with the exhibition, we spoke with the photographer about her work, personal philosophies and travels throughout Latin America.

LATINNESS: Graciela, we’re big admirers of your work. You began your film career at the age of 27, eventually dedicating your life to photography. Tell us what these early days were like for you.

GRACIELA: Before I got married, when I was young, I wanted to study literature, but I come from a very conservative family. In the sixties, I had already finished high school, and although my dream was to go to university, I married very young and had three children… yet I stayed with the desire to be a writer.

At the age of 27 I heard there was a film school where they also gave scripts, and I said to myself: “Maybe I can write something there.” I was very interested in that specifically, the writing and the photography. In fact, I made a short film that I’m now restoring because I found material on a famous painter at the time, José Luis Cuevas, whom I was able to interview before he died. Since he had a very good memory, he remembered everything. I did that for two and a half years.

Later, I discovered photography through Manuel Álvarez Bravo, whom I assisted at film school. I loved it. I could travel around the country and to other destinations with one or two cameras without a problem; not like when I studied film, where I had to carry bigger ones with lighting equipment and all that, so I didn’t feel capable, it was too much for me. I loved seeing him work and traveling with him to some towns… that’s how I fell in love with photography.

I also love cinema, but it doesn’t necessarily mean I suddenly feel like going back just because I worked with Iñárritu on Babel. Even so, at some point, I had nostalgia for the big screen. I love watching movies, especially Italian neorealism, Czech and Russian filmmakers. There are many that I like, such as Andréi Tarkovsky, because they also inspire my work.

Ultimately, I dedicated myself to photography. I began to travel, first within Mexico, to the towns. Eventually, I stopped working as Álvarez Bravo’s assistant; however, I’d visit him frequently, since he was more of a life coach than a photography teacher.

Graciela Ituribide by Martin Bellatin, 2021.

LATINNESS: He was a big influence on you…

GRACIELA: He was the complete opposite of my family: a free spirit. He’d been divorced. I remember one day he told me about it: “Graciela, divorce is fine because one begins again” Soon I got divorced, and it was very easy. He taught me a lot of things that, having been raised in a conservative family, I wasn’t used to hearing.

For me it was a liberation. A realization that “Oh, life is not necessarily as I was taught; there are other possibilities”. I’ve always read a lot, and Manuel did the same. Sometimes, in the afternoons, we would listen to opera because he loved it, and he would recommend that I read books about culture and go see exhibitions. He told me that he hadn’t considered an education with the composition of the great writers, and that Picasso was very important to him, especially when he was young. He says he changed his life.

I think that Manuel Álvarez Bravo taught me to be myself. I learned that there were many things inside me that I wasn’t familiar with because of the education I had. I studied in a school with very strict nuns, where, luckily, I was able to access the literature of the Spanish Golden Age, and since I loved reading, I was happy with that part. I also learned a lot, especially to love my solitude.

Ironically, I was only single for a year when I left school because I got married so quickly. After raising my three children, I worked with Manuel, and then I began going on my own to the indigenous communities. I learned a lot while living with them, there was a lot of complicity with their members. It was really nice getting to know my country through the camera.

After that, I started traveling around the world. I always say that the camera is a pretext to get to know it and to get to know yourself.

Cristina Taking Photos, White Fence, East L.A., United States, 1986.

LATINNESS: Your curiosity as a writer is very evident…

GRACIELA: Yes, truthfully, yes. And I keep writing, but my dreams. I also really like reading literature and poetry. Sometimes I wonder what would’ve been, but I’m very happy as a photographer. I love it.

LATINNESS: And look at everything you’ve achieved through it, as well.

GRACIELA: No, I haven’t achieved much, but I love it.

LATINNESS: You reflected on Manuel Álvarez Bravo so beautifully. Have you mentored other creatives throughout your career?

GRACIELA: I have, but not many. In the last administration, there was a National Council for Culture and the Arts (Conaculta) and the National Fund for the Arts (Fonca), and they frequently sent us invitations. For example, I was a National Prize winner and once I had an exhibition, so I tutored a few people. Many of them still come to me, like Maya Goded. When I met her, she was very young. She always showed me her work. In fact, when I went to Hungary, I invited her to join me on the trip.

I’m not much of a tutor because I travel frequently, but there are many people who show me their work, especially former students, for example, from the workshop I gave in Arles, France while exhibiting there. I also mentored some in Barcelona, although we went to photograph for only a few days, and here in Mexico.

The other day Aristeo Jiménez, who is from Monterrey and takes incredible photos, visited; he’s an excellent photographer. He didn’t really require much help, but we did chat about where to exhibit.

I have a relationship with my young students, more than my children, who did photography workshops. Some wanted to be photographers, but they ultimately didn’t continue. My grandchildren also take photos, although they don’t dedicate themselves to it. Even so, many of my friends did photography workshops with them.

LATINNESS: Speaking of your travels, as a woman and a mother, did you face any kind of prejudice while traveling the world alone back then?

GRACIELA: After traveling with Manuel, mostly to nearby towns, I went alone to Juchitán at the invitation of Francisco Toledo. Then I did another job in the Botanical Garden, but funnily enough, I’m a feminist, and I never had problems. In fact, sometimes being a woman worked in my favor because the women in the communities —and the men—, especially those from Juchitán, helped me. They took me in their cars or in their trucks to other places. I lived in their houses and ate delicious food. I always felt a great complicity with these people.

It’s interesting because, when I traveled to Madagascar with Doctors Without Borders, I also had that protection. Besides, I wasn’t alone… and everyone wanted a photo. In India, too. There, sometimes, I had guides, or a friend who would tell me where I could go. Nothing ever happened to me for being a woman, although sometimes it could be dangerous. But I didn’t experience it. On the contrary, one day I went to a fair where they were selling horses… There were a lot of people and everyone wanted a photo. So I told Natalia, who was with me: “Pick up your camera because I can’t take a picture of everyone.”

I photograph what happens in each place, but I never do it if I see that people don’t welcome it. I don’t like to take photos without the complicity of people, so I speak with them. I also don’t use my cell phone to photograph people without them noticing. I accept that some photographers do and it works out very well for them, but I don’t. I need closeness.

So no, I’ve never had a problem being a woman. On the contrary, as a photographer it helps me. Maybe in other situations I’ve had issues, but as a photographer, never.

LATINNESS: We’re curious about your predilection for black and white photographs, especially in a region known for its colors.

GRACIELA: Personally, color is hard for me.I feel like it’s not reality. How odd, right? The ones I did in color were for the Instituto Nacional Indigenista (INI) but these were commissions for their magazines and transparencies that are no longer used. Although reality is in color, translating it on camera is a bit hard.

Recently, the Cartier Foundation asked me to do a small color series for an exhibition in Paris, and I said yes. Of course, I went to a place with many stones, and I love photographing them. I took a series of seven photos. I like the ones I chose, white, but the ones with many colors make me think: “No, what did I do?” However, they liked it. As for the public, some will like it and others will surely say “How horrible!”

I got accustomed to photographing in black and white, to abstract reality, its lights and shadows. Black hues help me to make compositions more easily than color.

Color is more difficult for me. Sony gave me a digital camera a year ago, and although I don’t take digital, only analog, I had to comply because they’re very kind. So I’m trying to do a color series, but I’m going to investigate well so that the photos are soft and clear. I have to learn to use it to achieve a good result in color.

Self-portrait, Sonora Desert, Mexico, 1979.

LATINNESS: We’re very curious to see those photos.

GRACIELA: I’ll show them to you, I promise.

LATINNESS: If we accompanied you on a photography trip, what would your process be like?

GRACIELA: It’s always a surprise. With Doctors Without Borders, for example, I photographed whatever I wanted. In Madagascar it was very easy because the children went to check-up with their parents, and I could travel with a driver or go alone to take pictures. But in any of my journeys, it’s always the surprise that causes a reaction.

In the case of Italy, where I was working for about a year, coming and going, I chose the late film director Pier Paolo Pasolini, as my intellectual guide to influence me. He was also a writer and essayist. Still, the surprise was the most important thing. Then in Rome, apart from going to the Cinecittà– a film studio and television complex– and walking through the city streets as early as six in the morning, I worked in Ostia, which is nearby and is the place where Pasolini was killed.

Now that I think about it, I have guides, maybe a bit spiritual or maybe literature. In India I read many books about that country. I mean, I always try to read about the places I’m in or talk to older people. They hold many legends that can serve as inspiration, right? For example, Pasolini’s tomb in Ostia, which belongs to the Communist Party and is in a horrible state, I didn’t photograph it, if anything the stones, or if I saw something that spoke to my heart because I don’t follow scripts. The heart, the eye and intelligence are my guides when it comes to shooting.

Little Mexican Angel, Chalma, Mexico, 1983.

LATINNESS: You’re Mexican. How do you compare the country you began to photograph in the seventies with today?

GRACIELA: We have a pueblo that’s very pretty, and very close. That said, I can’t photograph violence, even though I’ve photographed political things, my soul can’t stand violence.

Sometimes, by chance, I’m asked to, for example, with UNHCR, the UN refugee agency. They commissioned me to photograph the Mara Salvatrucha [criminal gang] who arrived in Oaxaca, as well as the displaced people in Colombia. It really affected me. Yes, it’s a testimony, however, more than photography, what’s important is that civil society does things differently. Fortunately here there are protests.

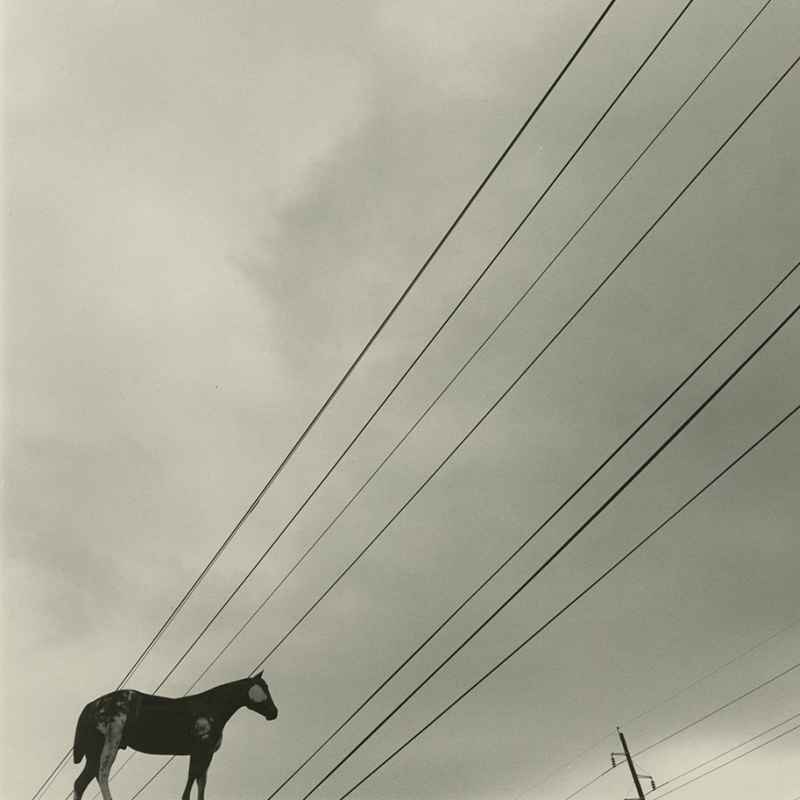

Tehuantepec, Oaxaca, Mexico, 1985.

LATINNESS: You’ve said that photography is a pretext to discover life and culture in the places that you visit. Since the seventies, you’ve toured Latin America offering different points of view from many countries. Any anecdotes you can share?

GRACIELA: In Panama everything was wonderful. I traveled to photograph the local people, and coincidentally, met Omar Torrijos in a region of the Guaymí Indians. He asked me: “What channel do you work for?”, as if I were on television. “No, I’m from Mexico,” I replied. “Oh, well, I want to talk to you so that you know some nice stories,” he said. He was very worried about the daughter of Mama Chi, the then deceased Guaymí leader, because before he was a general, when he was a simple soldier, he had pursued her. So, I was so naive; I never saw corruption in him.

I don’t like people in power, but I feel that he was a magnificent person. That same day he told me: “I’m very sad, Graciela,” and I replied: “Why, general?” He said, “It’s just that they didn’t introduce me to Mama Chi’s daughter.” So I asked “Why do you want to meet her?” He responded: “Because I wasn’t there, Graciela. Can you imagine if I had a child with her? Our child would be the leader of Latin America.” Very cute, isn’t it? I lived through things like that with him.

In fact, he would consult the peasants to find out how they saw the country. Gregorio, above all. I have many photos of Gregorio with him. He would ask him: “Let’s see, Gregorio, how do you see Panama? How do you see the field? And he did what Gregorio or the peasants told him. And when he went with the indigenous communities — sometimes I accompanied him because he was working with the three indigenous zones of Panama—it was always a very nice experience. I could see that, despite being people in power, they wanted to do things to help.

And well, to begin with, you have to see what he did with the Panama Canal. I admire him a lot because he managed to reclaim it. I accompanied him when he went to see Jimmy Carter, which I didn’t realize until now — at that time I didn’t realize it, because I was ignorant — helped Torrijos and Latin America a lot. Later I felt regret because when I did the Torrijos book they told me: “Do you want Carter to write a text?”, and I thought: “No, why?”. One makes a lot of mistakes in life.

Torrijos had an assistant, José de Jesús Martínez, who was Nicaraguan; he helped the war in the country, with weapons and money. That’s why I’m very sad about the situation because I was fascinated by the Nicaraguan Revolution, but now I see that Mr. Ortega is a dictator. He’s putting his former comrades, the revolutionaries, in jail.

You believe in things, the camera helps you; then, you stop believing, the camera helps you, and like that, you start to reflect and modify your perspective.

These were very important experiences for me, both Cuba and Panama, even though I no longer agree on many things.

Magnolia, Juchitan, Oaxaca, Mexico, 1979.

LATINNESS: And what lessons do you take with you?

GRACIELA: I always say that through the camera lens you can discover the world, society and yourself. Also how your mentality changes and how you have to protest.

These trips, and everything that’s happened to me in life, have helped me finish forming myself as a person.

LATINNESS: You’ve witnessed important historical moments. Speaking of which, you photographed Frida Kahlo’s intimate objects that were discovered in her bathroom after more than half a century. I remember I was working at Vogue at the time, and we did the exhibition “Appearances Can Be Deceiving: Frida Kahlo’s Dresses”, a project that really impacted us. What was that experience like for you?

GRACIELA: It was amazing! Hilda Trujillo, who was the director of the Frida Kahlo Museum, told me: “Come! We are going to create a book on Frida Kahlo for the 50th anniversary of her death.” Her husband Diego Rivera, when he passed, had asked that all her belongings, which remained locked up 15 years after her departure, finally be revealed, but it never got done.

When the closets and rooms were eventually opened, Hilda wanted me to photograph the huipiles they found. I told her “Hilda, I’m not one of those photographers. Yet when I went through the bathroom, it was half open and I saw that the tub was full of all these objects related to her pain: her crutches, her corsets, her medicines, political posters… So I asked Hilda: “Do you think I can photograph the bathroom?” And she replied “Of course you can!” I did not photograph the huipiles though, and the next day I was dedicated to photographing and arranging the entire bathroom.

Later, I reinterpreted everything. I used the corsets in which she documented herself, her Chinese shoes — the ones she used when they cut off her leg — she had many of the same… The stuffed turtles, the birds. It was very hard for me because even the smell was intense.

I photographed each object of pain and therapy. I’m not a “Fridomaniac”, but there in that bathroom I realized how valuable this woman was. Because even with back problems and without a leg, she chose the therapy of painting wonderful things, fueled by her fertile imagination.

Those who were close to her say that Diego sometimes gave her a little help. Juan Soriano, who was very close to them, confirmed it. But Frida’s imagination was wonderful, wonderful. In photographing her bathroom, I couldn’t help but have admiration for her.

For many Mexicans and Chicanos in the United States, she is Santa Frida. And well. I say: “it’s not all that.” In other words, yes, she suffered, but in Mexico we really like pain, saints, blood, this, that, and since she suffered so much, they made her a bit of a saint. In fact, her museum is visited by people from all over. And well, for me it was very difficult, but it was also a lesson: “Look at this woman with so much pain, with so many problems and her therapy was to paint….” How wonderful, right? Frida also taught me a lot.

Jaipur, Rajastan, India, 1999.

LATINNESS: In recent years you’ve stopped photographing people. Why?

GRACIELA: Because I love my planet and it’s not limited to people; there are also the stones, the landscapes, the birds… I just got back from the Canary Islands, in Lanzarote, where I was happy photographing the lava from the volcanoes. I went to speak at a conference, and I stayed there for a month. I recognized our origin and the evolution of the human being: from the volcanoes to under the sea. A lesson for me.

I would like to photograph everything on the planet. And it’s that, little by little, your interests change. I also went to the erupting volcano in La Palma, but I couldn’t get close enough to photograph it, and at night, black and white didn’t suit me… It was like a postcard. To hear the roar of the volcano was to witness the birth of life. Wonderful! That’s why I say that everything leaves you something. Now I want to photograph volcanoes.

When they built the studio I’m in, about four years ago, there was a lot of lava. Xitle is a volcano that exploded thousands of years ago and whose lava formed the Pedregal de San Ángel colonia. The architect Luis Barragán began to build houses in this small neighborhood. I also found lava and pre-Hispanic figures.

Now I’m constructing another smaller building next to my house, for my grandchildren. I already told them: “Dig, please, because I want figurines, and if there is lava, save it for me.” I’m moved by this curiosity to know what my planet is like.

Chalma, Mexico, 2008.

LATINNESS: Out of curiosity, do you have a favorite camera?

GGRACIELA: I always use Leica and Mamiya; however, my favorite is a Rolleiflex from the 1940s. It doesn’t have an exposure meter, so you must have another camera, but it has a high quality lens. Whenever I can, I take it, even though it only gets a roll of 12.

LATINNESS: Before we close, you mentioned that a few movies have inspired your work. Can you recommend any?

GGRACIELA: By Andréi Tarkovski, Nostalghia and Andrei Rublev. The latter is like the history of art through images. If you haven’t seen it, do so because it’s wonderful. For me, Tarkovsky is a genius and a great inspiration.