María Teresa Hincapié, Vitrina, 1990. Courtesy of Magda Bernal.

COFFEE WITH

A CONVERSATION WITH CLAUDIA SEGURA AND EMILIANO VALDÉS ON MARÍA TERESA HINCAPIÉ

By Jennifer Burris

Names: Claudia Segura and Emiliano Valdés

Profession: Curator of Exhibitions and Collection, Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona

(MACBA)/Chief Curator, Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín (MAMM)

Nationality: Spanish/Guatemalan

Zodiac Sign: Gemini/Scorpio

Instagram: @claussegura/@emilianovaldes

On March 16, 2022, the first retrospective dedicated to artist María Teresa Hincapié opened at MAMM in

Medellin with live performances, a packed auditorium, and crowds drawn from the city’s diverse

communities. In the following conversation, the exhibition’s co-curators speak about Hincapié’s work as a

driving influence on their respective curatorial practices as well as on their personal philosophies.

View of the exhibition Hacer Hincapié de Mapa Teatro (2022) in front and Una cosa es una cosa by María Teresa Hincapié (1990 / 2005 / 2022) in the background. Courtesy of the MAMM.

Jennifer Burris (JB): Who was María Teresa Hincapié? What was it about her work that drew you

both to this project?

Emiliano Valdés (EV): María Teresa Hincapié was a Colombian artist. She was born in Armenia in 1954 and died in Bogotá in 2008. A pioneer of performance and especially of durational performance–which is a particular type of action-oriented art–she trained in theater so her notion of performativity comes through that perspective. Because of that, she managed to open a new space for the body in the visual arts and helped change the history of Colombian art.

Claudia Segura (CS): Moreover, she had a very interesting conception of art and a practice that is very difficult to categorize. It oscillates between an artistic practice and a quest for the sacred. When she was first leaving the theater field she started to do actions that she called “trainings.” Only after some years did she begin to incorporate the word “performance.” From the very beginning she was looking for an elasticity in the performative field.

EV: Not only did she innovate in terms of artistic vocabularies, but she also addressed issues that were as urgent then as they are now: ecology, the relationship to various indigenous communities, and this idea of spirituality and the sacred, as Claudia said. It’s interesting to see how the topics she treated when she was most active in the 1990s are still so pertinent and so current.

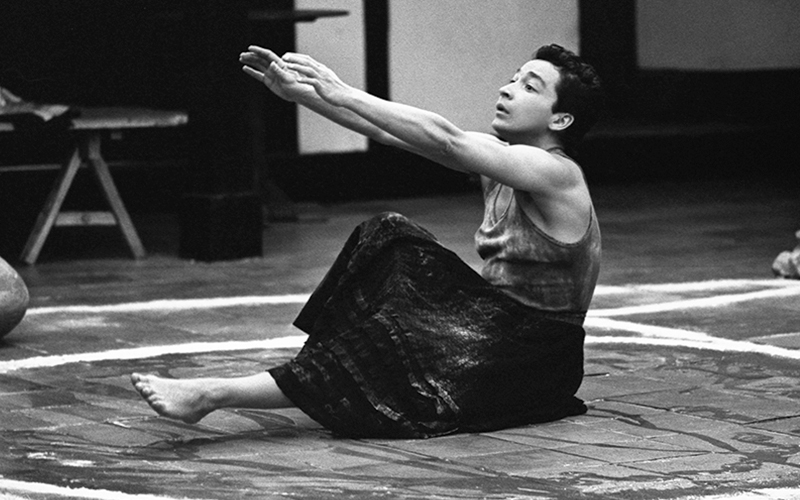

María Teresa Hincapié, Ondina (versión dancística), 1986. Courtesy of Santiago Zuluaga, Casas Riegner, Bogotá, and 1 Mira, Madrid, Madrid.

JB: Following this sense of the now: a compelling aspect of your curatorial approach is the incorporation of living artists like María José Arjona, Coco Fusco, José Alejandro Restrepo, and Mapa Teatro. Why did you engage new commissions within the exhibition framework of a retrospective, which is traditionally oriented towards the past?

CS: Since the beginning of the process we knew that we had to work with archival material because María Teresa is no longer with us. It was really complicated to think about an exhibition that was intended to show a more open sense of performance when we primarily had archives and two-dimensional materials to work with. In her practice, María Teresa was very interested in her relationship to the community; specifically, how can knowledge be produced by a community through orality and engagement with other artists and people? In that sense, we thought that it would be very interesting to invite four artists to establish a posthumous dialogue with her; to understand the archive as something that is changing and can be transformed.

María José Arjona was a student of Hincapié’s and is also a performer engaging with long duration. She was so moved to create this work. At the same time, the founders of Mapa Teatro [Heidi and Rolf Abderhalden] lived with María Teresa during the nineties. They are a collective that works in the liminal space between theater and performance. In that sense, they share a lot with Hincapié’s practice. Coco Fusco, who is the last artist invited, knew and also coincided with Hincapié in exhibitions like the Bienal de la Habana and a group show at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. It’s very beautiful how all of them engaged the archive in different and specific ways, but always with the energy of Hincapié’s practice.

María Teresa Hincapié, Vitrina, 1990. Courtesy of Santiago Zuluaga, Casas Riegner, Bogotá, and 1 Mira Madrid, Madrid.

EV: From an exhibition-making perspective, one of our main goals was to show Hincapié’s work to a wider audience because she had always remained a sort of niche character. If we had stayed with an archive-only exhibition it would have been drier. We wanted to present the work in a way that was interesting and engaging. We wanted people to feel and understand what she wanted to achieve through her actions and we felt that one way to do that was through either performance or actual works, rather than pure documentation.

We had long discussions about whether to include re-enactments in the exhibition, which is a typical way of bringing back past performances, especially by dead artists. We ended up moving away from this because her practice was so much about her own experience; we felt that engaging other artists’ experiences was a way of giving flesh to the exhibition while also giving the opportunity to viewers and visitors to feel bodies doing things around them in real time, which is what happened with María Teresa when she was alive. By creating a space that recovered or recuperated these initial intentions, in combination with other practices, we tried to deepen the experience of learning about her work.

CS: The few resignifications that we did do of specific works were made in collaboration with María Teresa’s son. He has been part of the exhibition throughout–someone with whom we have had an ongoing dialogue–and all recreations were done with Santiago’s consent.

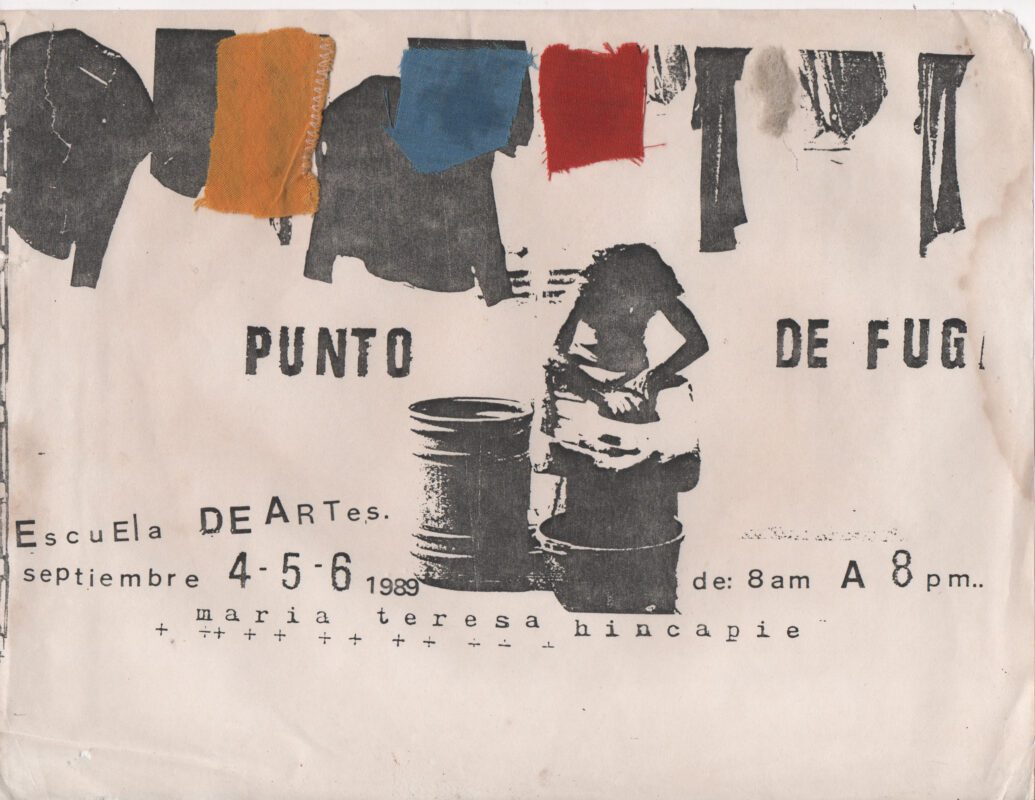

Invitation to Punto de fuga (1989) intervened. María Teresa Hincapié Archive. Courtesy of Santiago Zuluaga, Galerías Casa Riegner, Bogotá, and 1 Mira Madrid, Madrid.

JB: In describing the process of curating, you both foreground relationships with people. Just as you describe an exhibition as a personal experience set alongside an encounter with other bodies. How do both descriptions influence your ideas of what a curator is or what a curator does?

EV: One of the synonyms of curator I like best is “exhibition maker,” which is a term that Harald Szeemann used. Szeemann, for the wider audience, was one of the first independent curators. The term refers to overlooking and engaging with all aspects of making an exhibition, which are truly so many. In my case, because I tend to lose attention rather quickly, this wide universe is attractive because it keeps me busy. It involves getting to know an artist’s work thoroughly enough so that you can communicate it fluently. It also has to do with the actual organization of an exhibition, which involves being in relation to a whole series of processes and dynamics and social systems. And then, finally, communicating: writing texts, having conversations like this one, publishing books, and all the many things that come after an exhibition opens. It’s a multitasking career, but one that allows you to get to know the work of people that have quite literally changed the history of culture and art. That is a huge privilege.

In this particular case, and I think I speak for both of us, getting to know María Teresa Hincapié in such depth has had an effect on the way I think about things like spirituality and my relationship to the earth. My relationship with different communities.

View of the exhibition with performance En silencio pero juntos by María José Arjona in collaboration with Camilo Acosta (2022). Courtesy of the MAMM.

CS: Definitely, I couldn’t agree more with Emiliano. There’s one aspect that is very important to how I understand curatorial practice, which is research. In this particular exhibition that research was archaeological, because we were confronted with an archive that hadn’t been previously looked at. It was a puzzle and we had to find the little pieces. This process not only involved working with documents but also talking to people who knew and worked with María Teresa, like her son. Emiliano and I also went on a sort of pilgrimage to La Fruta: the house and residency for a “Village-School” that María Teresa began to develop in 1996 in the vicinity of Quebrada Valencia in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. All of these things–a performativity of our own bodies implied in this expansive view of research–is something that is, in my opinion, incorporated in curatorial practice.

As Emiliano was saying, it’s true that having the privilege to study these artists as well as being able to decide on whom to focus–which artists are in effect going to be placed into the map of the history of art–is also a huge responsibility. Who you choose to focus on matters. I personally try to find artists that are in between spaces. María Teresa is well known in Colombia but she’s not that well known in the rest of the world. Additionally, she’s known in Colombia primarily as a myth. Going through this exercise of trying to understand and then show the shadows and lights of an artist–revealing the complexities of someone who thought in a completely different way and approached art with a completely different perspective from their moment, someone who pushed the limits–is very interesting to me. It obviously impacts the way I understand the exhibitions that I curate, as well as how I understand my own life.

Claudia Segura at the La Fruta farm, home of María Teresa Hincapié in the late 1990s, Quebrada Valencia, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Photography by Emiliano Valdes.

JB: So much of María Teresa Hincapié’s work seems tied to Colombia. You both are originally from other places–Guatemala and Barcelona–but have spent a significant part of your careers leading art institutions in this country. Could you describe the process of how you came to live here and how your time in Colombia has informed your perspective?

EV: I trained as an architect in Europe before completing a master’s degree in art history and the history of literature. Right after graduating, I went back to Guatemala where I started working as an architect with City Hall. That was a very frustrating experience. And so, together with a group of friends, I started a contemporary culture magazine comprising art, architecture, food, and lifestyle. Through the magazine I started to become acquainted with the art scene. At first, we wrote articles on artists but soon we realized that it was much more interesting to invite artists to do things with the magazine directly. At the end of the magazine’s first year we organized an exhibition. I remember thinking at the opening that this is an amazing way of telling stories. It opened up an entire world for me. My family was always close to the arts–my grandmother played music and had a small collection–but organizing that first show really showed me that you can use exhibitions as a medium to share and translate entire ideas about the world through the lens of art. It’s an incredible thing if you think about it: the fact that there are objects and processes that allow you to look at the world in a way that nothing or no one else does. It has a flexibility and freedom that is truly unusual.

So I started pursuing that. I became friends with artists, and I started working in galleries and institutions like the Reina Sofía in Madrid (where I had a fellowship). Before I knew it I had become a curator. Years later, I was the Associate Curator for the tenth Gwangju Biennale when I received a call from the Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín (MAMM). This was 2014 and MAMM was about to open their Expansión building; they were looking for a Chief Curator to help steer the institution through a moment of expansion. This expansion refers not only to growth in physical terms, but also implied a rethinking of their project as a museum. Luckily, I got the position.

At the time I was living between London and South Korea, which was incredible but also exhausting, and I wanted to go back to Latin America. There have been such great things happening here in the last ten years. We’re lucky to be at the center of discussions about art worldwide. This is also a great place to think about what art is for. Returning to the ideas that María Teresa’s work engages with, which is trying to make people’s lives better in one way or another. And that has happened. MAMM is a warm, incredible place and we’ve been lucky to be able to do projects like this: exhibitions that I hope tap into people’s lives and show ways of rethinking things that you often take for granted in order to see the world through a different lens.

Claudia Segura and Emiliano Valdés at the opening conference of the María Teresa Hincapié exhibition, Si éste fuera un principio de infinito. Courtesy of the MAMM.

CS: It’s similar to me because I wanted to be a journalist at first, but I soon realized I was more interested in the creativity of language. I was pursuing my BA in the humanities, specializing in art and philosophy, when I took an amazing course in contemporary art theory from a professor who was then the head of collections at MACBA. I thought: this is what I want to do. I then received a scholarship for a master’s degree in contemporary art theory, but still wasn’t sure if this translated to curatorial practice. It was only after I interned at the Tate Modern in London that I discovered how interested I was in research, and that I wanted to be a curator.

I moved back to Barcelona and worked at Fundación La Caixa, focusing on cultural programming that used art as a social tool. At the same time I started doing independent curatorial projects and working at a gallery to be more in contact with artists. At that point, my partner was relocated to Turkey for his job and I decided to move with him. I thought it was a nice opportunity to devote more attention to my independent projects. While in Turkey I worked on the Mardin Biennale with a diverse group of twenty curators. This is a tiny biennale that takes place in a village twenty kilometers away from Syria. The organization operates in a completely different way from everything I had learned about art theory at Goldsmiths and about curating at Tate. It deconstructed all my knowledge.

Claudia Segura giving a guided tour of the María Teresa Hincapié exhibition, Si éste fuera un principio de infinito. Courtesy of the MAMM.

My partner and I then had the opportunity to move again: either New Delhi or Bogotá. I preferred Bogotá because I was interested in Latin American art and artists. When I was an intern at the Tate, I had met the curator José Roca who had this amazing residency and exhibition project in Bogotá called FLORA Ars+Natura; he asked me to be the editor of the first edition of FLORA magazine after I arrived in Bogotá. I then met Claudia Hakim, who had a site-specific project called NC-Arte in the neighborhood of La Macarena in Bogotá. The institution was five years old at that point and they were discussing next steps. We started having conversations on curatorial education and everything moved forward from there. I fell in love with Bogotá, with Colombia and its people, with the art scene, and with the South-to-South dialogue that you could establish here. It’s a completely different conversation to what is coming from Europe. This helped me understand art in a way that incorporates indigenous worldviews, among many other things.

After spending four and a half years in Bogotá my partner and I moved back to Barcelona. We had a little kid and wanted to be closer to our families. I applied to an open call for the curator of exhibitions and collections at MACBA and got the position. I really miss my experience in Colombia though, it was incredibly important for my development and still informs the way I see curatorial practice.

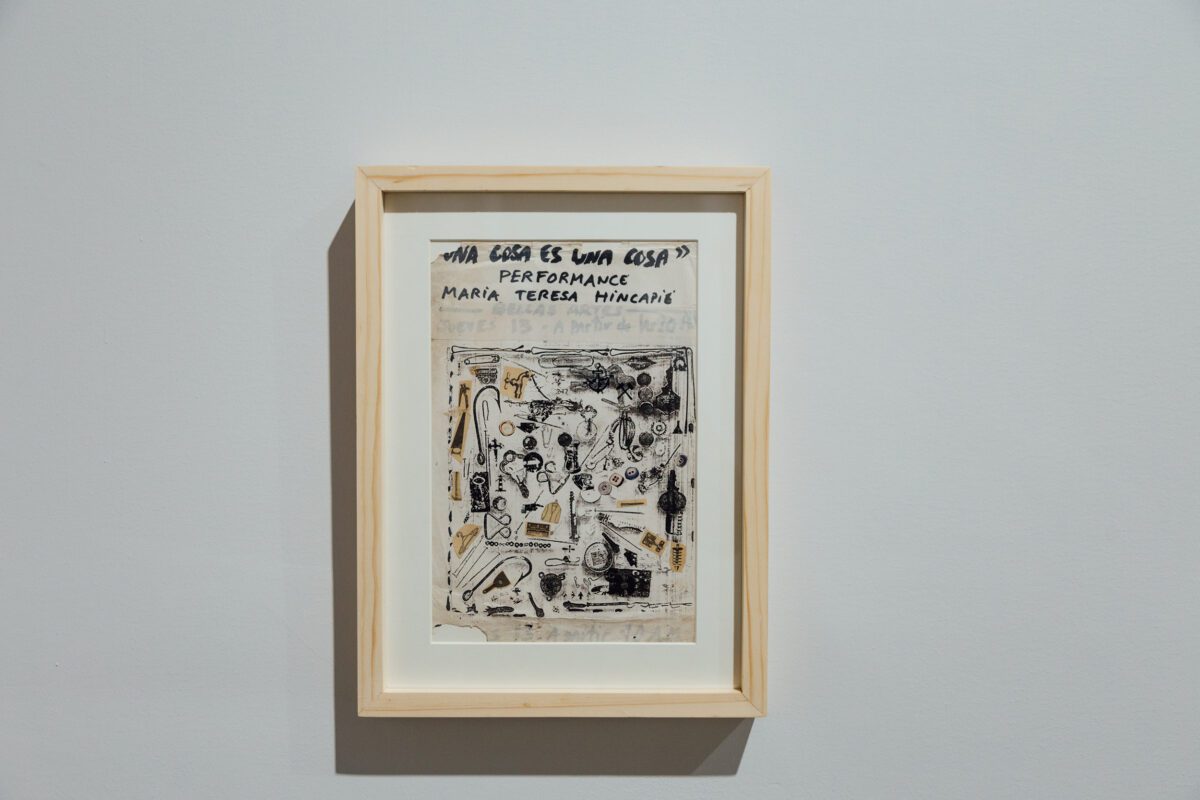

María Teresa Hincapié, Una cosa es una cosa, 1990. Installation with personal objects, variable measures. Leo Katz Collection.

JB: You both talk about your interest in telling stories, and how the types of stories told are indelibly shaped by who is speaking and where they are speaking from. How knowledge is always situated in both culture and context. What stories are artists in Colombia most compelled by at this point in time?

EV: Big question. It’s interesting to think about it. We organized an exhibition here at MAMM called PASADO TIEMPO FUTURO. Arte en Colombia en el siglo XXI, which was sort of a collection of significant works that had been produced in the country between 2000 and 2019. The exhibition is two years old now, so it might be a little outdated. I do nevertheless feel like it does gather some of those general intentions. Bringing together that group of works gave us a sense of what the most prominent narratives in Colombian artistic production were.

One of them had to do with the recognition of the importance of non-hegemonic forms of knowledge: going back to communities and marginalized groups, people who haven’t necessarily held the power or called the shots. That was a big chapter of that exhibition. Artists were saying, hey, we’re not really listening to the whole story. There’s a whole side that’s missing. Another focus had to do with war, but surprisingly not as overarchingly as we thought it would be. That’s still a concern in Colombian art: violence, guerrillas, all of that. But it has diminished. People have moved on from that concern or are framing it in a different way. I think that’s interesting. I completely relate to that. I’m not saying it’s about moving forward from a conflict, but I do feel that there’s a need to change and evolve in the way we relate to that kind of problem. That was really encouraging.

There was another direction that had to do with the development of the country itself and its many complexities. Colombia is a large country; there are many narratives and many issues. Coming to terms with that complexity is something that many artists engage with, which is a quest where I also locate María Teresa’s work. It has to do with finding meaning today through a renewed relationship with ourselves and with others. One that in turn makes us think about how we relate with existence: what place do we think we have in this world and what is the sense of us being here? It’s a topic that I’m personally interested in because I have a spiritual practice that is not necessarily related to any religion. But I think art can fulfill a meaningful role in those questions, especially for people who have a more eclectic spiritual belief system. We’ve seen it for years now, even centuries maybe: artists using art to connect to the sacred. I think that’s something that we see again in María Teresa. I appreciate that because it gives us tools through which we might live full and fulfilled daily lives. Whether it’s by understanding our daily actions as rituals or whether it’s because it gives us the chance of connecting to the sublime.

Reconstruction of El espacio se mueve despacio (2004) as part of the María Teresa Hincapié exhibition, Si éste fuera un principio de infinito. Cortesía MAMM.

CS: I agree. Spirituality is very relevant. These practices open different portals and try to communicate with voices that are far from the so-called “rational,” and that have therefore been relegated to a secondary level despite their importance. I think that such practices also force us to change how we collect and how we exhibit work: how we understand the role of an exhibition in a museum. With these bodies of work we are often engaging ephemeral objects or practices that are linked to communities and cannot be acquired. In that sense, it’s important to understand that they must be approached from a non-hegemonic perspective. They force us to rethink what a museum does and what a collection is. This is something that is very present in Colombia as well as in the Global South more broadly.

JB: So much of our conversation has been focused on the past or the present. But what about the future? Who are the writers, artists, and thinkers that you look to and that you continue to return to as you move forward?

EV: As I mentioned, my first degree is in architecture. I recently started a master’s program in urban and environmental processes. I’m going back to this idea of urbanism. It’s occupying a lot of my intellectual space and time. Given the current world circumstances, and the fact that now more than half of the population lives in cities, issues related to land and how we plan are key to securing a sustainable future. María Teresa is a fantastic example of how artists can relate to very pressing and real issues such as ecology.

I hate to be self-referential, but, again, I think María Teresa is such a fantastic character that we’ve had the pleasure to dedicate years to. Now we can share that with our audiences. She’s by no means the only one, of course. But she does epitomize some of those explorations.

CS: I’m not really interested in practices that refer to themselves, those that engage the history of art or formalist debates, but rather practices that try to establish bridges with other disciplines and other questions. Practices that try to understand what it is to be alive. Art that asks of itself existential questions. Obviously Hincapié is one of the best examples. There are echoes in her practice of artists like Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape. These are the references that always accompany my research.

This exhibition will be inaugurated at MACBA in Barcelona on October 19, 2022.