COFFEE WITH

SIMON VEGA: “IT WAS A RISK TO SAY I’M GOING TO LIVE BY THE SEA AND TRY TO LIVE OFF MY ART”

Name: Simon Vega

Profession: Artist

Place of birth: San Salvador, El Salvador

Zodiac sign: Scorpio

Instagram: @simonvegaestudio

LATINNESS: We’d like to start from the beginning. What led you to the art world?

SIMON: From an early age I loved drawing, like many young boys. When I started studying, I first chose Graphic Design (at the time there was no Art degree in El Salvador). I did it for two years, but then was lucky enough to travel to Mexico, to the state of Veracruz specifically, where I trained in Plastic Arts.

Drawing is something that I’ve always maintained, and which remains a basic in my day to day life. As a student, I got into the wave of exposing and presenting work, both inside and outside of university. When I returned to El Salvador, I already had this interest in exploring new languages, or at least what this meant for us. We were coming out of a twelve-year war in El Salvador, so we were behind on everything. Until then, video and performance art had barely arrived.

I started working on installation art in the year 2000, approximately, and presenting drawings, installation and ephemeral sculpture. Little by little, this led to invitations to prestigious international exhibitions such as the Central American Biennial and a biennial at Museo del Barrio in New York, and like that I was able to build a career.

LATINNESS: In looking at your work, there are many architectural references. Did you ever dream of becoming an architect?

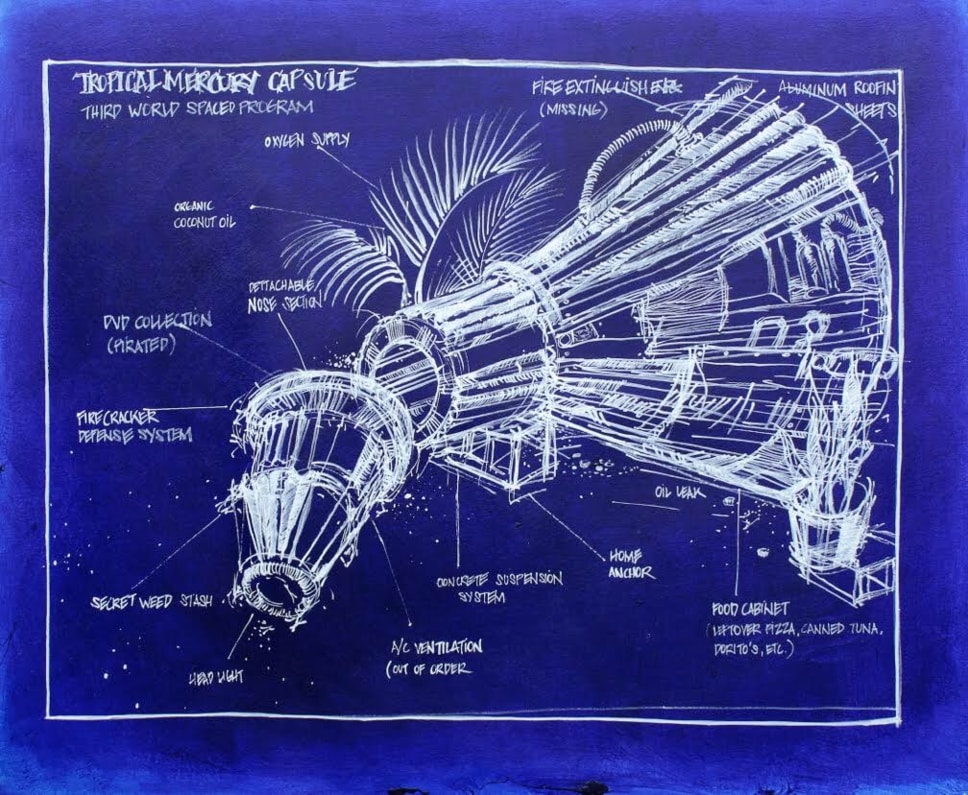

SIMON: Without a doubt. I also dreamed of being an astronaut, mechanic and archaeologist. Some elements of these disciplines appear constantly in my work. I never studied architecture, but I did study Graphic Design, and it was quite traditional. In fact, I did linear drawing, which has its relation to architecture. There were also references to the Bauhaus and the use of isometrics with many of the artists and teachers, which leaked into my work.

I always liked industrial drawing and the diagrams or icons to decipher the operation of a blender or a mixer. How do you put together an Ikea table? That kind of thing I loved.

So yes, architecture operates a lot in my work at a conceptual level. I have an extensive series called “Lost Cities”. It is a kind of game, a round trip between the dreams of early 20th century modernism architecture and these great architects -Frank Lloyd Wright, Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe and the link with Bauhaus- and the great utopias they expressed themselves through with this art, both on the communist and capitalist sides, and everything in between.

Architecture for me was always an element of reference that I had very present and that I wanted to combine with the opposite. In El Salvador, a country where we have swept away the pre-Hispanic and colonial architecture that we had- there is very little left- we also swept away a lot of the good that was made in the 19th and 20th centuries. So, having lost that, there is this desire of mine to recover and mix this great architecture with what is marginal and informal, which is found in El Salvador, and is also part of my work.

LATINNESS: You work with diverse materials. How do you select them?

SIMON: Well, in these last two series, what I have done the most, especially in sculpture, is a dialogue with marginal areas. I studied in these places for a year, and thoroughly investigated the informal architecture made by people in very poor sectors. You find it in any area, both rural and urban. For example, a fence made of pieces of sheet metal, wood, and signs to protect against anyone entering. The same goes for the walls of houses. That is what I see around me and it is present in my work, as well as the palm trees, the sea and a lot of things regularly considered positive.

But inside the houses -we say champas for those that are very poor- there are super interesting aesthetic elements. In the mixture of this pastiche of materials, such as corrugated sheets in cardboard and well-used wood, you can find one of these houses where the roof is missing a corrugated sheet for “x” reason, but thanks to this, a light enters that would not otherwise. Or you discover there is a plant downstairs … Those things seem magical to me. I don’t see it as poverty, but as a very lively mixture, like a very lively architecture. I use these materials I’m surrounded by.

When I started with sculpture, I wanted bigger works, but I didn’t have access to materials, so I wasn’t going to be able to do it in aluminum or other things. I was interested in translating something very sophisticated into something very “do it yourself”. It’s a bit absurd and ironic, so that’s why I’m choosing materials that also have their history, they have life. They have rust, they are worn, they tell a story, they carry a great load of texture… And by making a lot of ephemeral sculpture, I am freed from it lasting, right?

In other words, what lasts is the idea and the base drawing, and I can do it again. I assemble a capsule first here, then in another country. Each time it is destroyed, and it is rebuilt on site so the materials from that city also influence my work. That is why a piece can vary a lot or slightly depending on the country where it is located. For example, making a montage in Europe is a problem for me, because these materials do not exist, especially in the center of the continent. However, if you go a little east or work in certain cities in the United States, or in Mexico or Colombia, I have access to everything. That makes it easier and I love it. It is a part of my job that I like: going to ” find junk” in those places that you would not normally see on a tourist trip.

LATINNESS: The works in your series “Tropical Space Projects” are sustainable by nature with your use of discarded materials, or what today is called upcycling. How important is sustainability to your work?

SIMON: It’s not something I intentionally want to highlight; it’s just a natural response of wanting to work in a certain way and on a certain scale, wanting to work where I’m going. In many ways, it is also a response to costs, that is, to what I could pay at the beginning to make a sculpture of these characteristics, and so that interests me.

I use the idea of recycling and having a greater awareness of the possibilities offered by things that were only used once. They have color, they have their grace, they have their logo… it’s possible to use them. Here on the beach it’s very common to find plastic tides that have gone around several times, so it looks very worn. The sea has been filing it down, wears it down, gives it a patina; that also comes into play.

Although the reference in my work is not very direct, it’s important to see that something else results from that, that it has a certain beauty and that there is criticism. It becomes more relevant in the historical, political and economic part. The fact that it is built with this is an opportunity to reflect this condition of excessive consumerism in which we live, this excessive way of disposing of materials, the damage to nature and the power to recover these things and give them a second life. Terrific, right?

In fact, I love bringing these materials back. Many times I travel with suitcases full of them. There are very small things that I will not find in another country and that fit together thanks to transculturality and through art. Thus begins a new cycle.

LATINNESS: Interesting if they stop you at customs…

SIMON: Customs is always tell me the same thing: “And what’s all this for?” When it comes to plastic, it’s not that much of a problem, but when it’s metal, honestly yes … I bet you they look like bombs or something similar on x-rays. But hey, this is the extreme case. I usually scour the place for what I need.

LATINNESS: You are a multifaceted artist, applying drawing, sculpture and installation to your work. How easy is it to move from one discipline to another?

SIMON: At the beginning, it was a bit more complicated, because in my case, I always started from drawing. As for sculpture, the transition from drawing was less complex because they are closely related. I do a lot of drawing while thinking about sculpture. I do not do it as a drawing in itself, but to project how it will translate in the sculpture; sometimes I also present those drawings. Sometimes I draw from sculpture, that is, the reverse process. Although they look like blueprints, they are actually made after the fact.

Usually I develop the project without being guided by the aesthetic object, but only by the idea. With the theme of the Cold War and the space race, certain ideas led me to other techniques, like, it would look a lot better on video, for example. If the idea of the transmission of the event is worked on, as well as the historical documentation, a video can make a lot of sense. So, I move on to that and turn to experts for help. I’m pretty analog and pretty basic when it comes to digital, but I love working with other people.

In that back and forth of the explanation, something else emerges. For this reason, a lot of my work is collaborative, because the projects grow or the ramifications get bigger. So that’s how I got into video and performance, as something very playful. If I have, for example, masks, I say: “let’s play and see what comes out”. It is not as serious as “I’m an old artist and I must know this and that.” However, sometimes to present in a very large format, I turn to others for advice. Maybe I will work with someone with better equipment.

This is very natural. I get tired of sitting, and I love to go looking for materials. Then comes a slightly more physical-artistic part, when it comes to sculpture: drilling, for example. Then sometimes I go into a studio and work editing and audio with someone, which I also like a lot.

Everything is part of the same. You’re talking about an idea and then you just think what language works best with. And if you do not know it, you can consult with someone who knows it and do it together.

LATINNESS: How do you know when an installation is finished?

SIMON: In my case, I work with very precise drawings, which show how the sculpture has to look or how I want an installation to look. So if it’s a booth for a fair or if it’s a gallery, I usually ask for photos of the available space and work my drawings around it. In the end, even if you see a piece of garbage or wood, everything is well thought out, and it is quite similar to the drawing. Of course, at the moment there may be other things that call for change, such as the lighting, which is why I don’t always feel what I do is finished. I think it presents itself at a time where it already has everything it needs to communicate what it wants, and suddenly the piece can continue to live, and in fact, it does. Many are transformed and many continue their lives. Or they are re-done. Either elements are added to them or I might take a photo with a sculpture. Like the materials, everything is in a kind of fluid and transition; things just change. They go back to their origin, then they are transformed again, as in the case of the works when they are finished.

LATINNESS: You’ve participated in several artistic residencies throughout your career. How did these opportunities arise and how do they contribute to your work?

SIMON: It’s been a while since I’ve done it. At the beginning of the career, I think they are very important because they give you the opportunity to see your work from another point of view, and compare it with people from other countries who may be in the mood for an exchange. There are residencies that are just that: mixing people. There are residencies that are like a cabin in a forest, and you do your work there too.

I was always more interested in the residencies in which I had the opportunity to talk with other artists and access other ideas and things that I did not have in El Salvador, because although there is a very good and solid community of artists here, it’s very small. Of course, at the beginning, I had to look for them, ask for recommendations, and talk to the curators. That’s how I managed to do some in Miami; it went super well for me. The first was LegalArt, then Cannonball and Fountainhead Residency. These opened a lot of doors for me, and not only to contemporary art, but also to deep friendships and relationships that have turned into artistic collaborations.

Then I did some others, like last year at the Papaya Playa Project, in Tulum. Many times your gallery recommends you. Hilger, a gallery I work with in Vienna, recommended Fountainhead, and MAIA Contemporary, with whom I work in CDMX, proposed the residency project in this very cool and organic hotel in Tulum. They gave me a cabin facing the sea for a month with everything and room service. That type of residency is more of a vacation, but I always produce the same, because I love it. And well, in the end, they hope there will be a kind of open studio, at least one talk, which in the case of Papaya Playa there was, and it was super positive. The gallery is very involved.

LATINNESS: How did the “Palm 3 World Station” project for Coachella 2018 come about?

SIMON: That piece was actually something very special in my career as an artist, because you don’t always have the opportunity to create such a grand piece. I was making sculpture and moving a little more internationally. A year ago, a piece of mine had been acquired by the PAMM, the Pérez Art Museum, in Miami, for its permanent collection. It was in an exhibition that lasted like two years there. It was a Mercury, a capsule based on NASA’s Mercury, made of foil.

Rafi Lehrer, one of Coachella’s Art Directors, who travels the most, is always looking for artists who can create in those dimensions. He saw that piece and decided to get in contact with me. It turned out that another one of the Art Directors has an aunt who also lives in El Salvador. Through her, he contacted me and made a studio visit. Then they went to an exhibition that I had in Costa Rica, which was large-format sculpture.

We threw around some ideas of what would be cool at Coachella, and I sent them some sketches. It was a one year process. Finally, they liked the one on the space station and we started producing. It was like six months dedicated only to the design; I also spoke with some architects and engineers to see how we were going to do everything, that is, I had to translate to a large team of people how to build a marginal or favela and make manuals on that.

Then it was six months of production in the California desert. I made several trips in which I stayed up to a month to be at the forefront of the process with the team. It was an incredible experience, so dreamy. I worked with highly experienced lighting technicians.

In that space station there was a store, mini super or grocery store. I brought the strips of churros and toys from El Salvador… another interesting pass through customs. You couldn’t access them because everything was wrapped, but it was there. There were smoke machines, lights … It was an incredible experience.

Then, the festival itself and the interaction with people and with music is something that you don’t have in a gallery or museum, only in this event. It is putting your work into play, in another sphere and on another scale, a space station based on a real Soviet one. The MIR, like all the works in the series, is based on a real capsule, on a real space station.

Since we had to cover so much space and the space station only had seven modules, what I did was reproduce the others, for a total of thirty, based on the originals. That gave it the size without losing the scale and was what made it work well, as did the small pieces that had the same type of structure, but with other architectural and engineering considerations. I complemented the above with live plants, palm trees, lights and a lot of things. It was a monumental experience, literally.

LATINNESS: Did this platform effectively expose your art to a larger audience?

SIMON: Without a doubt. Look, in these types of events you realize how small the art world is and how big the world of music and entertainment is. That’s very interesting because then a lot of people start following you who didn’t before. For me it was, without a doubt, a super experience. And of course, now what has happened to me is if I want to mount something in a museum, any outdoor sculpture, the curators first say: “I mean, if this guy could handle this, he can handle anything else.”

So it would seem, but in reality it’s not like that, because everything is a question of resources. In other words, if you have them, it can be super fun, but if not, even a very small piece of work becomes a big headache. In this case, we had all the resources to do it.

LATINNESS: Talking about your works, which show the effects of a polarized society, such as what we are experiencing today, how do you see what is currently affecting and will affect post-Covid polarization?

SIMON: The “Tropical Space Projects” series talked about the effects of the Cold War in Central America; about that and the conflicts that affect El Salvador and Central America today. When I started, a little more than ten years ago, the polarization that existed in the case of El Salvador was much more latent, that is, between the two sides at that time: on the one hand, the extreme right, supported by the United States, and on the other, the extreme left guerrilla, supported by Cuba and the Soviet Union. So there was a very direct reflection of the Cold War issue in the political polarization of the country.

Now that has changed; we have other problems. We are even more polarized as a society, but the protagonists are not the same, so things change. You respond to the events that are around you, and obviously, this is so big and so global that, in one way or another, you are going to reflect some elements of it. For me, there is going to be a greater difference between rich and poor, between first and third world; There already was, but now it will be much greater.

A part of the middle class will disappear. The difference between rich and poor, between contaminated and uncontaminated, between societies free from this issue and others that are still suffering from it will be exacerbated. Personally, it seems very programmed to me. There is something under the water, no doubt.

I’m very apocalyptic in that sense, and I see things very post-apocalyptic from now on. That is getting into my job; I’m doing those kinds of relationships. I think that economic polarization is always political, and it is what will have more weight or will reflect a little more in my work.

LATINNESS: Will the current political climate make good art?

SIMON: It’s interesting to ask yourself what will happen to art and how it will change. Many of us try to imagine it. I think that, in the first instance, there are those who think everything will be digitized, and that’s it. Honestly, I feel it’s a resource that will be deepened and will give us more options, but it will not replace the experience. Of course, I’m sure it’s going to transform. In other words, it’s not only going to be about what you’re talking about, but how you’re going to present it, how it ‘s going to move and how and where it will be seen.

Will there be access? Some countries will continue as before with art fairs and everything. The galleries I work with in Europe, for example, are not going to do Art Basel this year, yet Art Basel will be held in Europe, where you can already travel and everything is much more protected. However, I am operating out of these centers on purpose; I never wanted to go live in those countries.

So how is that back and forth going to work? It’s something to speculate, right? In my case, I think it will be very positive, because many new things will emerge. I feel that we were very stuck in this question of the art market and its valuation through the fairs. I believe that now there is an opportunity to work in the community and locally. And beyond this: glocally. Glocalization.

Let’s see how much the situation extends in some places or in others. Without a doubt, beyond health and the virus, the economic issue is also going to be prolonged, and this will influence the way things are seen and consumed.

I think it will be positive in terms of novelty and criticism for sure, although, perhaps, we are not living in a better, more functional or more democratic society.

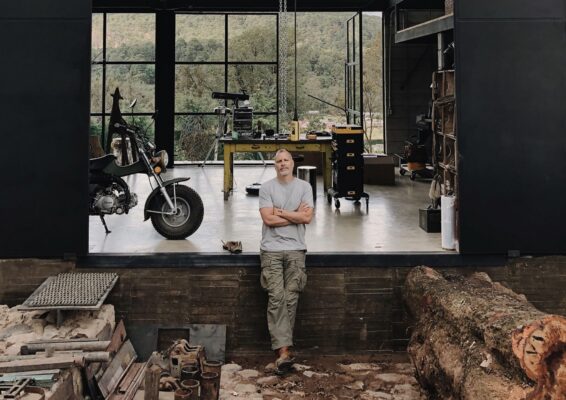

LATINNESS: And speaking about your center, why did you choose La Libertad as your base?

SIMON: It has to do with the sea. I am a person 100% connected to the sea. I was born in San Salvador, the capital city, which is 30 or 45 minutes from here; it’s super close.

My mother is full sea, so I learned to surf very early. It is one of the centers of my life … Flat out: there are two centers in my life, which are art and surfing.

For a long time I couldn’t, but every time I was able to, I came to surf. I’d go for about four hours a day, two days a week. Little by little, when I felt I was ready, I said: “I’m going to go live in the sea and I’m going to try to live off my art.” For many years I lived from teaching and giving classes. When I ventured to live only from art, I settled in La Libertad; I isolated myself to produce and to be able to move internationally, rather than nationally. So here I combine my two passions: art and surfing. I’m super happy.

LATINNESS: Since you dreamed of being an astronaut, what do you think of all the explorations that are taking place in space?

SIMON: I’ve always leaned more towards the past than to the present, but I am interested in this approach to space exploration, which is very different from the one that took place in the 1950s and 1960s. For example, I have a piece, the one in Tulum, on the project of the space hotel by the Russian Space Agency. I’m very interested in the idea of Noah’s ark, as well: “the world is going to implode and we are already hitting it, where are we going?”. It’s not just an idea, it’s science fiction. Who will go? Who will be chosen, and why? And what happens? Do they stay there?

Many of the ships are like that too. You see them, and it’s like something that was left in the past, but at the same time it’s like these people said “Ok, let’s build our own ship to save ourselves and we’re going to do it with what we have, no matter how absurd.” It goes with that idea, the idea of this playful game of getting ourselves to think and having a narrative or speculating a narrative for these experiments and these visions. People like Elon Musk, they are actually bringing a lot of freshness to the visualization of where these projects are going, which during the Space Race had a very “militarizing” edge, very much of the military competition between antagonists. Now it has another vision.

Images courtesy of Simon Vega.