Ana Gonzalez Rojas next to her work RACIMO, CATTLEYA 1/5 + 2 P/A at La Cometa gallery.

COFFEE WITH

ANA GONZALEZ ROJAS: “MY JOB AS AN ARTIST IS TO SOCIALIZE ISSUES THAT CAN BE TOLD IN A POETIC WAY”

Name: Ana Gonzalez Rojas

Profession: Artist

Nationality: Colombian

Zodiac Sign: Gemini

Instagram: @anagonzalezrojas

On October 25, during ARTBO, one of the most recognized contemporary art fairs in Latin America, La Cometa gallery in Bogota was witness to a conversation between Ana Gonzalez Rojas and LATINNESS in which they discussed the issues that are driving her work, the delicate process behind it and her role as a woman in the art world. Moët & Chandon accompanied the talk with a toast in honor of the Colombian artist.

LATINNESS: Ana, do you remember the moment you realized art was your calling? What was your first work?

ANA GONZALEZ: I knew I was an artist from a very young age. My mom remembers I won a prize when I was three years old for an elephant painting.

I’ve painted and drawn my entire life, but I knew I had to follow the artist’s journey when I painted this one dress, which has since been an obsession and a symbol for me, at least in Colombia. That was many years ago, about 20 or so.

It was then I understood that my path was to express myself through art, and so I set off on it.

LATINNESS: What’s your purpose as an artist?

ANA GONZALEZ: At first I painted and drew just to practice my trade, because I knew I had a knack for certain techniques until I understood that through them, and through the trade, I could talk about important issues in Colombia, such as forced displacement, mining or deforestation.

Little by little, things started taking shape. Today I think my job as an artist is to socialize issues that can be told in a very poetic way.

Sometimes words are not enough. The journalistic part —which is important— is not enough. Sometimes an image can say much more. A work can express much more. So, in that sense, I believe in the transformative power of art.

LATINNESS: What issues are currently driving your work?

ANA GONZALEZ: My work covers various issues, especially displacement. We are a country with many displaced people. I’ve been working with vulnerable communities in Colombia for several years: indigenous and peasants.

I also started working with nature. By traveling through Colombia I realized that we are losing the great treasure or the “Great Dorado”, which is our nature. So I understood I needed to focus on that: on social displacement and the displacement of species due to deforestation in Colombia and Latin America.

That’s my body of work. Especially the latter, because it’s what I’ve been working on for the last five years.

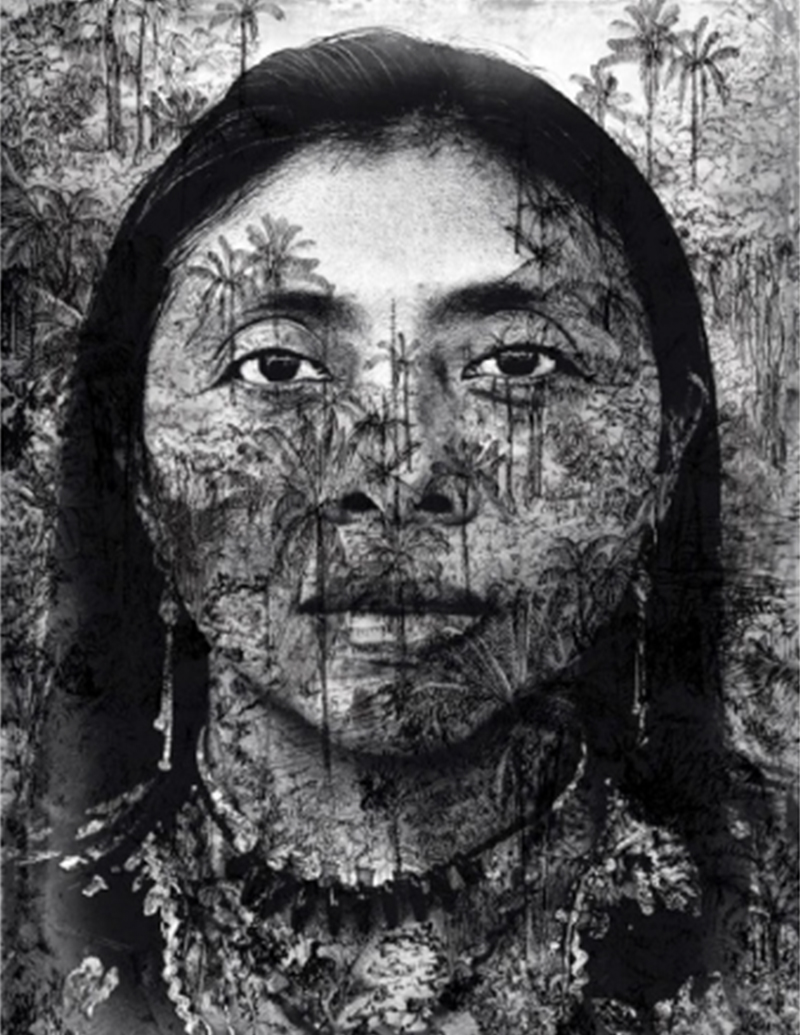

In conversation with Ana Gonzalez Rojas in front of her work CHOCÓ 95.

LATINNESS: This piece just behind us is part of this series, correct?

ANA GONZALEZ: Exactly. It’s a series on Chocó. Although sometimes I know the works have to speak for themselves —and I prefer that they do rather than make a philosophical treatise on them— I’ve approached the work in a much more intuitive than rational or philosophical way.

Here we have very simple and concrete ideas: this is Chocó, which has been repeatedly devastated by mining, by gold. Nature, as Humboldt said, is like a tapestry from thread to thread, and we are almost finishing with it. When one pulls the thread, something happens to the other side. That’s the landscape of these pieces on canvas or silk paintings.

LATINNESS: Speaking about your travels, has being a woman helped you develop relationships with the communities on these journeys?

ANA GONZALEZ: Colombia has been covered in large part by men, some of them anthropologists, and the chronicles we’ve had for several years, almost hundreds, are male; they have a very masculine vision of what nature is and what happens in it, not only in Colombia, but in most tropical countries.

My vision is much more intuitive, much less rational and classifying or identifying types. My approach is more from the heart.

I learned a lot from my coexistence with the indigenous communities on the journey I made for Hijas del Agua, which awakened my intuition and feeling more than understanding or trying to translate it into works.

The female gaze has a lot of that, which is why it’s important to validate it, because there is a very strong, rational masculine side, but also that intuitive feminine side that tends to balance the scales, something fundamental at this time.

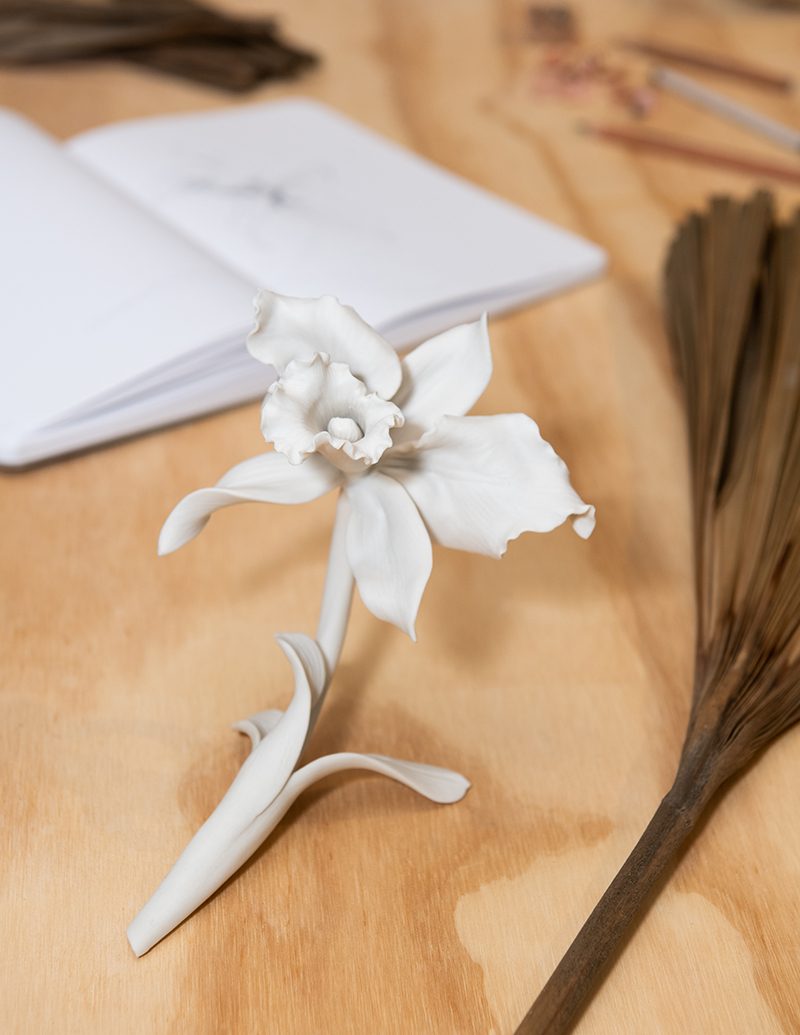

CATTLEYA RECOSTADA.

LATINNESS: Through your works you tell many stories about Colombian, often of realities that are harsh, yet you achieve it with a poetic balance through your choice of delicate materials. Can you tell us about your process and how you choose your materials?

ANA GONZALEZ: Through the materials, I seek to send a message, so according to that message, a specific material is found. It’s also that I get a little bored with the same material or the same job, so I try to change it up.

I work a lot with porcelain, watercolor and filigree. They are very delicate trades, but that’s precisely what interests me: talking about the fragility in nature and in society. That’s why I use materials such as silk and porcelain, and I work them by hand, placing a lot of emphasis on the trade, not on the work of the hands, which is very feminine.

LATINNESS: You’ve been able to explore a vast part of Colombia… Is there something that people don’t know about your country? Anything you’d like them to know?

ANA GONZALEZ: I’ve had the opportunity to tour Colombia for the last four or five years, a lot. And yes, I think there’s a message that I need to keep giving, which is: we tend to go outside, right? Since I was young, I traveled abroad a lot. I studied abroad, but really in seeing Colombia, the power is here, the material to inspire and not just the subject. From every job we have, we need to come together to protect what remains, because really, in these last ten years one can see that it’s less and less; fewer rainforests, fewer wastelands. There are many topics, but that’s the message.

LATINNESS: Sometimes the hours of work and research aren’t as evident in the final result, but they have a weight and a value in themselves. Why is it important for the viewer to understand the hours dedicated to a work?

ANA GONZALEZ: It’s like Haute Couture. When I lived and worked in Paris, I witnessed it, and I felt exactly the same way I feel now with works of art.

We all have the ability to generate a lot of knowledge to end up with a very specific product, but with a very strong story. However, to do it, to arrive at that porcelain or that work, they’ve spent countless hours of study and practice; that is not seen.

Sometimes people will ask: “Well, what is this work worth?”, and I answer them: “This piece is worth 2,000 hours of work”. That’s usually priceless. Many times that’s not understood or seen in most artists, whether they are conceptual, non-conceptual, figurative or whatever.

Hence the importance of seeing that a work, no matter how simple it may seem, has a knowledge and process that takes months and years, which are eventually summarized in a single piece.

LATINNESS: Do you start each piece with an idea or do you trust the process?

ANA GONZALEZ: Both. Sometimes I have a super clear idea and I achieve it. Other times, there is the idea, but nothing comes out of it. In a completed work, there are in general, about 20 or 30 behind it. At the beginning, the product is more incomplete than finished, which is why the work at the studio is super important to generate the final pieces.

The most important thing to me is the process. If you go to my workshop, you can see everything there, at least most of it, because I have other workshops where certain things are made. The process is as important as the finished work.

A toast with in honor of Ana Gonzalez Rojas at La Cometa gallery.

LATINNESS: The term “female gaze” is widely applied to the work of women artists. What do you think about this phrase?

ANA GONZALEZ: I think obviously there are certain trends right now. Now we are talking about feminine landscapes or that, for example, there is a feminine way of seeing the landscape.

Everyone has a way of seeing it. In my case, I see the landscape or external nature and associate it with my own landscapes. There’s a relationship between what is outside and what is inside.

At ARTBO you’ll see, for example, some of my works that are much more intimate, of my intimate landscapes, but that also have to do with nature. I approach them with a feminine look.

This is important because we’ve had the male gaze for many centuries, until this whole feminist trend came along, which was huge, and now we’re getting to that balance where the gaze becomes more feminine than feminist, and where we really start to talk, also from silence, from intimacy, from tranquility. Yet very relevant topics that are very powerful, even if they are not so strong and so easy to express.

Images by Manuela Montañez Guerra.