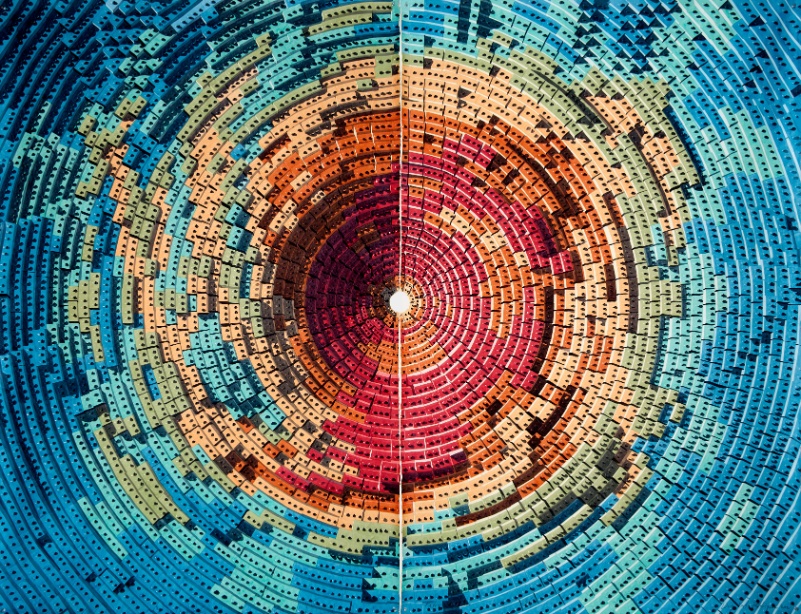

Puente Invertido, 2019.

Image by Sebastian Schaub.

COFFEE WITH

DAGOBERTO RODRIGUEZ: “A SOCIETY THAT DOES NOT EXERCISE CRITICISM AND IS NOT CAPABLE OF ACCEPTING IT, STAGNATES

Name: Dagoberto Rodríguez

Profession: Artist

Nationality: Cuban

Zodiac sign: Pisces

Instagram: @dago_rodriguez_carpintero

LATINNESS: Dagoberto, you use a lot of humor and irony in your work. Where do you see the space for this in the context of Russia’s recent invasion in Ukraine?

DAGOBERTO: Well, I haven’t quite understood the joke yet, you know? But what I can tell you is that in Cuba we’re trained to laugh at what happens. Humor has been one of the most effective survival mechanisms that we’ve had in the country during all these difficult years.

If you go to Cuba right now and ask anyone about it on the street, they’ll probably give you a comical response about what’s going on. Perhaps it’s indifference. I don’t know. It’s a very serious technique on a personal level that’s more about survival; It’s not that we’re so funny, but we’re forced to laugh a little at the situation we have, because it’s to commit suicide if you take it seriously.

A country that’s spent sixty years with a government that’s not capable of guaranteeing a glass of milk to a child… imagine. What can I tell you there? Either you laugh or you die. It’s our struggle.

Of course, my work is permeated by all these conservation strategies, but in my case, they’re work strategies. For me, getting a smile out of someone through a work of art is very important. I don’t always get it. Even so, it’s essential to me to have that point of view. It’s a tremendous lesson.

Maracas y morteros.

LATINNESS: I love that reflection. Since your split with Los Carpinteros in 2018, how has your practice oscillated from collective to individual intention? How does that influence your work?

DAGOBERTO: Well, let’s see, when Paul McCartney parted ways with the Beatles he didn’t start partying. Neither did I. When I disassociated myself from Los Carpinteros, my work was in inertia, as were all the investigations that I was carrying out within the group. There were a series of giant concerns that I had on my side and others that were from Marco. In these five years, what I’ve done is continue those lines of research and that practice.

My work remains extremely collaborative. I always try to create synergy with other disciplines. I did theater, but I’ve focused much more on audiovisuals. I made two pieces of NFTs and I’ve continued to develop all the concerns that, at one point, originated in Los Carpinteros; I’ve expanded them. They’ve been expanding and that’s what my work is today.

Maybe you look at it and say: “Some things are very related”, but there are others that are completely disconnected. They are investigations that have led to something else. And well, I think this has been my methodology, my strategy, the work in my daily praxis.

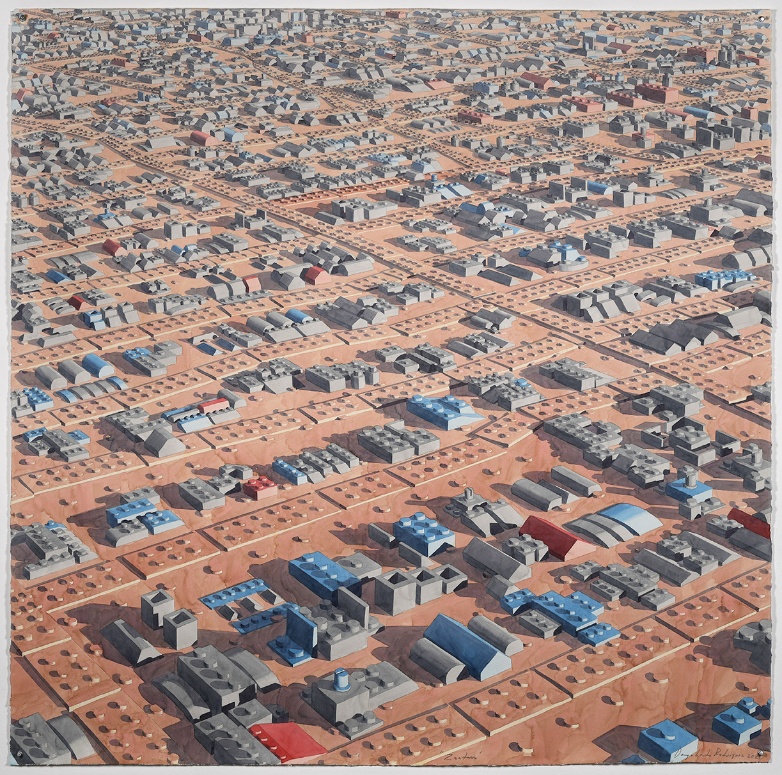

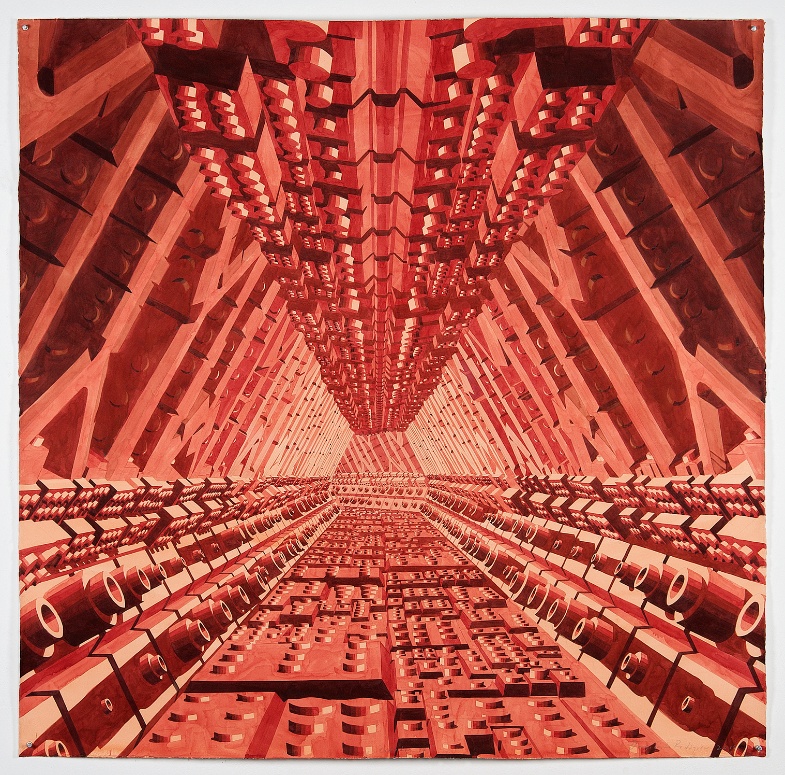

Katrina, 2021, watercolor on paper.

From left: Zaatari, 2021; Corredor XIV, 2019, both watercolor on paper.

LATINNESS: We’d like to talk about your work with watercolors. It’s a specific choice of medium in relation to the subject of architecture. What’s your relationship with and interest in it?

DAGOBERT: Girl, I love watercolor! It’s a technique that housewives used in the past when they were bored at home. Before the invention of photography, this was the fastest and freshest method of recording reality.

On all his research trips, Darwin brought a painter, and it was usually a guy who did some killer watercolors. This person had an enormous weight in registering and conceiving what the world was like, especially in the 19th century. Later it became a kind of technique that fell into disuse a bit, although the German expressionists used it a lot.

I was interested because it was something that cost me a lot of work to assimilate. One doesn’t learn to do watercolor in one day. The first works were pretty bad. Very, very bad, and they looked like that until I started getting the hang of it. And after you learn, it’s very difficult to move on to something else.

Now I’m doing many works on canvas, a bit like watercolor, which is quite transparent and without pasting. I don’t like oil paste.

These are technical details, but I’ve tried to continue projecting what I had been doing in watercolor and transfer it to the canvas. It’s what I practice the most, it’s what I know how to do best.

Dagoberto Rodriguez.

LATINNESS: So it’s an aesthetic issue and not a position, because conceptualism is, in a certain way, the opposite of technique, which represents a material like watercolor.

DAGOBERTO: Yes it is. Conceptualism bores me a bit. I consider myself more of a baroque artist. In fact, I live as if it were the nineteenth century. What I really like the least is minimalism. I liked it when I was a student, and sometimes, when it comes to thinking, I have a certain minimalist thought in many details, but when I’m going to conceive a project, my work is extremely baroque.

Refugio I, 2019.

Images by Conde Duque.

LATINNESS: You have an affinity for architecture. How do you compare the roles of the artist and the architect in society, particularly in Latin America?

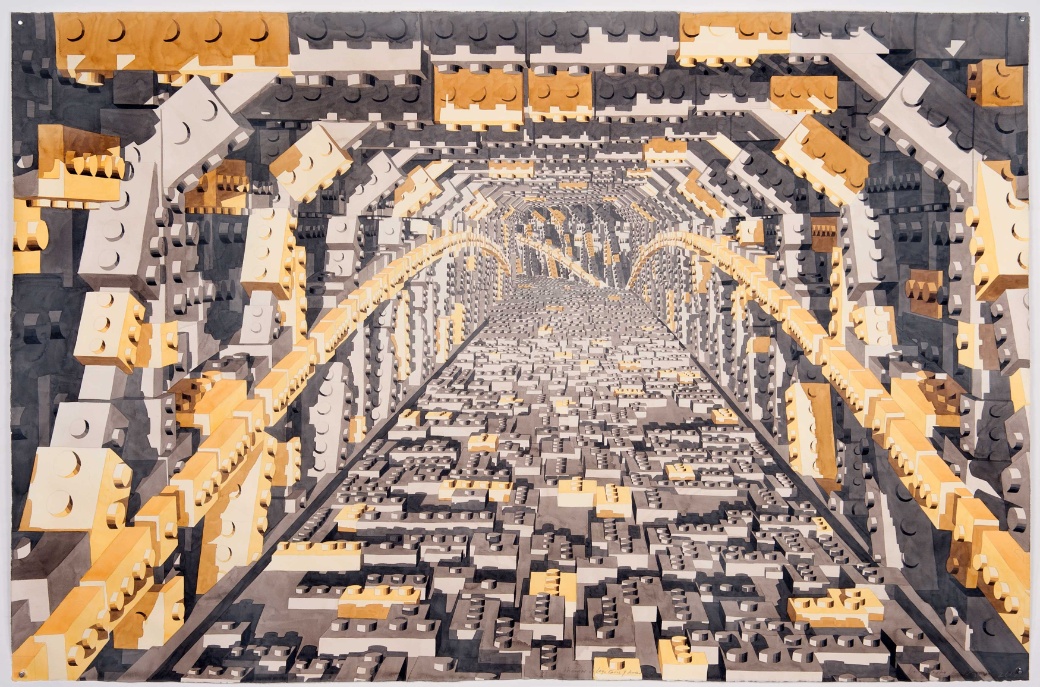

DAGOBERT: I was always interested in the vital space that one needs to live, not so much in architecture. That place, the four or five meters that one uses the most in his life, fascinates me. I love being on a plane and seeing how the seat, the little light and the bathroom are arranged. How they manage to compact everything, just like on trains and ships. It amazes me how things are placed so they don’t fall.

In recent years, my work has speculated a lot about futuristic architecture; for example, how life has been seen tomorrow inside a spaceship. I am interested in this discipline, because basically, it’s our only method of salvation.

When it came to the issue of the pandemic, what helped us was to isolate ourselves from the world where a virus was prowling. That’s why I’m interested in architecture as a method of survival.

This art lost its narrative quality when the printing press was invented. All those things that were written on the doors of the churches and that told you the story of Jesus and the Way of the Cross, were lost. Architecture used to be the book of humanity, but that no longer exists, and I would like to return to it. I want it to be what it was before: something capable of telling a story. I’m very interested in its narrative language, what it can say.

Last year I was in Egypt, and they are building a new city in Cairo. When you observe this new Cairo from above, you realize that they’ve followed a kind of pattern with a language that can be perceived from above, it can be read. It’s like a text. It’s awesome. Maybe it’s kitsch, maybe it doesn’t work well as architecture, but you have to see it from that perspective. That’s interesting to me.

Umbral I y Umbral II, 2022.

Image by Conde Duque.

LATINNESS: We are curious to know if when you started, there were any restrictions for artists in Cuba.

DAGOBERTO: We started our practice in the early nineties. A decade ago, in Cuba, all those who graduated from schools, and especially in the mid-eighties and who were related to the cultural environment in the city of Havana, thought that something was going to happen in those days.

The Soviet Union was undergoing a restructuring process based on transparency, and the press was much more open… open to criticism. The artist community believed this was going to happen in Cuba. Unfortunately, it didn’t happen, and the Cuban government became cloistered in an impressive communist orthodoxy.

Most of the artists of that generation emigrated to the United States, because they did not find space in their country. They were persecuted and censored in Cuba. We call them “the generation of the eighties”.

When we started, we wanted to separate ourselves from what had happened with the artists who had to leave. We learned the lesson: you have to speak through metaphor.

That’s where humor also comes from, because it was very important to survive as an artist at that time, using jokes and double meanings as a discursive strategy. We were trained in that. That is our battlefield. In it we began to create. That was the cultural environment in which Los Carpinteros emerged.

No Estrellas, 2019-2020.

Naúfrago 1 and Naúfrago 2 in Rodriguez’s studio.

LATINNESS: And is it still the current environment for artists?

DAGOBERTO: Now it’s worse. When the government understood the joke that the art they saw in galleries was more of an art against them, they enforced a law in the Constitution that said that any offense against the State would be penalized. This is article 343, if I remember correctly.

This article has been devastating for Cuban culture, because it has put an end to critical thought in Cuba. A society that does not examine itself, regardless of anything, is a society that does not procreate, does not progress in any way. A society that does not exercise criticism and is not capable of accepting it, stagnates. It does not go anywhere, and that’s what’s happening in Cuba. They’ve put it by decree that you cannot criticize, so it’s very difficult to improve that.

Many in the Cuban government react to criticism from artists or people as if it were something harmful. They don’t realize that most of the people who are criticizing the government are doing so because they love this country and want to make it better, but they don’t understand that. They see it as if it were a hostile thing. It seems to me of tremendous brutality and ignorance.

In my time we could still allow ourselves a certain level of criticism without going to jail, and that, unfortunately, is not happening now.

LATINNESS: Do you still reside between the two cities or are you based in Madrid?

DAGOBERTO: I live more in Madrid. I go less to Havana now. I’m still interested in the city, because it’s a tremendously inspiring place. I have my house there, my dog, but the trips are less and less frequent.

After spending thirteen years in Madrid, I don’t have that pressure. I don’t suffer from those nostalgias that occur at the beginning. That’s been left behind.

My son was born here, and that makes one rethink life a lot and organize things in a different way.

Gray and Amber Lego Tunnel, 2019.

LATINNESS: And now where are you?

DAGOBERTO: My favorite work is almost usually the last one. I work a lot, I believe in enthusiasm and what I’m most passionate about is usually the most recent.

I feel tremendously excited about the four things that I’m developing now. I like them and think about them frequently. I go over them again and again, and that’s my favorite work.

A palo Limpio, video, 2021.

LATINNESS: Do you think that art can change the world?

DAGOBERTO: Look, I used to not think so. I always considered that art portrayed, yet did not change, but in the case of Cuba, there’s a generation of artists, which emerged especially in these years that I’ve been away, who have managed to plant a seed. The seed of a tree called democracy that I don’t know when it will come out. Perhaps it takes many years, but it was planted and that’s admirable.

I thought that art was not capable of doing any of this, and I was wrong. It’s happening in Cuba, and the young ‘kids’ have done it, exposing themselves to the police with tremendous courage, really.

LATINNESS: Artists like you planted the seed of using art as resistance.

DAGOBERTO: Totally, we fixed the land, we fertilized it, but they planted it.

Images courtesy of Dagoberto Rodríguez; special thanks to Galeria La Cometa.