CAFECITO CON

JAVIER REYES: “DESIGN CAN GO A LONG WAY IN SOLVING PROBLEMS THAT HAVE ARISEN FROM INEQUALITY”

Name: Javier Reyes

Profession: Designer, Founder of Rrres

Place of birth: Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

Instagram: @rrrrrr.es

LATINNESS: Javier, through your project Rrres we see a mixture of cultures. You are Dominican, but lived in Spain, and now are based in Mexico. How did you get started in the world of design?

JAVIER: I´m from the Dominican Republic and lived a part of my life there. I lived in Buenos Aires for about three years to study graphic design, and I always felt a great connection to photography. I was very attracted to that part of design, such as collages, mixing photos with other elements. Then I returned to my native country and stayed there for two years before leaving for Barcelona, where I stayed for five years. I wasn’t studying or working directly with anything that linked me to the city, but that’s when the project was born.

LATINNESS: How did these experiences in Argentina, Spain, and of course, in your native Dominican Republic, influence the beginning of this adventure?

JAVIER: When you live in different contexts for more than a year, or even two, seeing the other culture you live in — especially if it is not Latin, but European — makes you remember things from your own. I began to think about the artisanal, in that craft and manual world that remains latent in Latin America, and especially in the Dominican Republic. Of course, there are other continents that have it, but Latin America was what I knew. With that background, I reflected: “Wow, this is incredible! I had not seen it before with this potential or with these eyes. We have to do something”. My project arose as a naive initiative of “let’s see what happens”.

LATINNESS: Talk to us about the purpose behind Rrres.

JAVIER: The initiative was born because I like working with people and getting into different realities. Visiting communities or towns that you might never go to. The project connects two people from different cultures or different social backgrounds. That was the only thing that interested me at first, that organic part of speaking with communities and learning from them.

I came from working in graphic design and image consulting and development, where the work was a bit cold towards the end. Everything is done remotely, by computer, and very sedentary.

Living in Europe, away from my homeland, made me realize that something was missing. That’s how I began working with artisans from the Dominican Republic, linking them with Europe. It all started like this: I worked on some ideas with the artisans and brought them to that continent; made presentations and photos. I was looking for a way to show a little of what happens on this side of the world, that we’re not just little palm trees and colors, not the naïve or typical.

LATINNESS: And what brought you to Mexico?

JAVIER: I realized that in the Dominican Republic it was very difficult to do this work. The artisans were scattered and very few remained, which was another reason that motivated me to do the project because I wanted to help preserve these artisan cultures.

I’m not really about flags and patriotism. I can come to Colombia and still feel that Latin soul. In the end, we’re all human, right? Wherever you go, there is a disadvantaged sector, and if one can contribute or collaborate, why not do it? The initiative arose from this.

I came to Mexico because I knew this great artisan development still exists here, and there are communities dedicated to this work.

Let’s say the process is easier here, there is a community dedicated to this, so it’s about knocking on doors and sitting down with them. This was not even possible in the Dominican Republic, and I’m sure in many parts of Latin America, where the designer has to make more of an effort and venture out further in order to get close to them.

LATINNESS: Sometimes that effort is what intimidates many creatives. How was that experience of arriving alone in Oaxaca and getting closer to the artisans?

JAVIER: Everything has been an adventure, and at first a little improvised. When I arrived here three or four years ago, I began to investigate which places were more or less close, where they worked certain techniques, and that it wouldn’t take me two, three or four hours to get there. I wanted to create side by side with the artisans, to be there with them.

I would go into stores and pretend to be a tourist, not even speaking Spanish. I’d ask things like: How much does it cost? Where can you see this piece? Where do they do this? They don’t tell you anything if they see that you are one of those astute Latinos, whom in the Dominican Republic we call tigueraje, because they think you want to copy them or mount something similar to theirs.

Sometimes I managed to get information from them, and once you are here, you figure things out little by little, but at first, I didn’t know anything. I would consult books or search the internet. Many are already more into technology, so step by step, I went about shaping things.

LATINNESS: From arriving alone without a single contact to building a well-recognized design studio is the dream of many artists. What was that journey like?

JAVIER: I didn’t move to Oaxaca immediately, it took me two years to make the decision. I was living in Barcelona, and would come and go. At first, when I started with the rugs, I’d travel from Oaxaca to the communities in local trucks or buses. I did it three or four times a week, but it was frustrating because when you work with artisans, until they can understand what you’re trying to achieve, you have to be there with them.

I realized that this was not working, and it was them who invited me. They told me: “Mr. Javier”, and I was like: “Please, don’t call me that, Mr. Javier sounds like my father, a 72-year-old!” And they continued: “Look, why don’t you come here and stay in one of our rooms?” At that moment, I laughed, thinking it was a joke. “That would be crazy,” I thought, but then I reflected and thought, “Why not?” And so I stayed with them.

I’d stay for two-month periods, and in fact, we lived like this for a while. Between one period and another, I decided to leave everything in Barcelona and move. I set up the studio here and started a routine. Of course now I have a car because the artisans are half an hour or forty minutes away. I go to see them every week, and sit with them- it’s been incredible. This pace has allowed me to really build things, especially large-scale projects in which we can guarantee delivery times because I’m here. The initiative has evolved; we create projects and make deliveries, things are happening.

LATINNESS: Which communities are you working with?

JAVIER: In Oaxaca there are three main cultures: Zapotec, Mixtec and Mixe. Most of those near the city are Zapotec. There are others who do not identify with any of these, they do not speak Mixtec, but I’m sure they had Zapotec three or four generations ago. So, I work with these different Zapotec communities with techniques based on textiles or the use of clay. Then there are the artisans from Sierra de Guerrero, a little outside of Oaxaca, and they focus on palm weaving.

LATINNESS: What other techniques do you use in the studio? How do you decide which to work with?

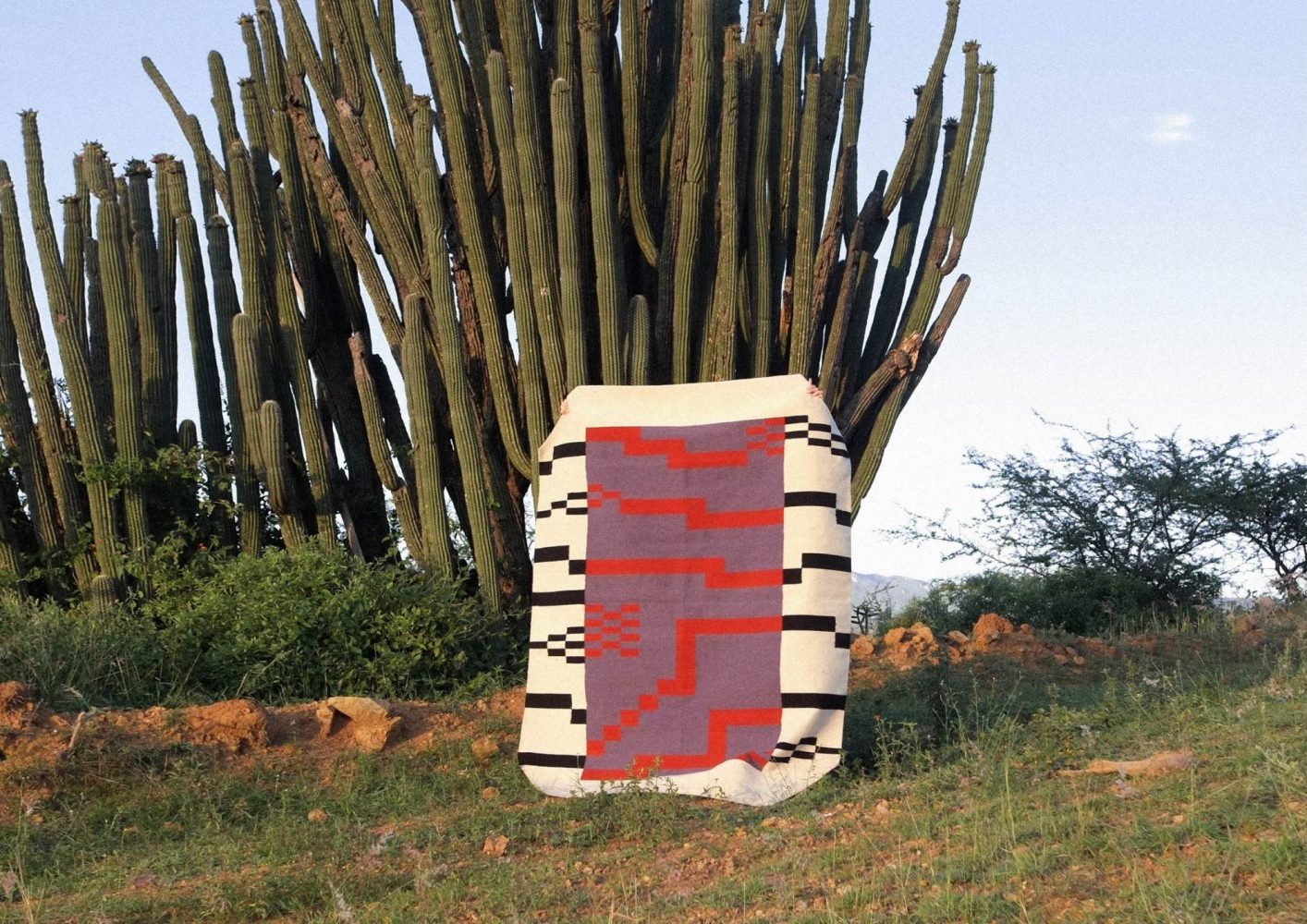

JAVIER: We are beginning to weave with cotton fiber to create blankets and throws, but it’s taken us time. I thought that instead of working many different techniques, it was better to go little by little until I managed one with the craftsman and supported him to consolidate a monthly production with his family. If not, it’s wasteful. You have to help them organize themselves. The rugs have worked very well because there is a lot of demand. That technique was what excited me five years ago when I sought out to build this dream. Now I’ve managed to work with three families; there are about 12 or 15 weavers, and each group has assembled its own workshop.

We’ve helped organize them by doing what is necessary: keeping the accounts, investing in looms or pigments. We have to tell them: “Hey, don’t wait for work to come; go uniting these colors, because they are what we always do”. This is the dynamic. They themselves have ideas and they are also taking shape. There is a big difference between this style of working with artisans versus: “Here’s the work, let me know when it’s ready and I’ll come to pick it up. “

Each piece and technique I venture into leaves me with the satisfaction of rebuilding that spirit and being able to create together with them. Each technique I work with comes with a responsibility with the families, of trying to propose pieces and ideas that have an actual market. In the end, yes, they should be pretty designs, but I think a lot about the practical part of it. Do I see a market, a value? Am I going to be able to get clients?

Personally, I feel I have to be more and more practical in many things, and ensure they have a minimum job so that they also believe in the project, and that their children or new generations can see it as a way of working. That takes a long time.

LATINNESS: In the creative world, you hear much more about Oaxaca, in artisanal terms, in comparison to other Mexican towns and communities. Why is this?

JAVIER: In Oaxaca artisans are more empowered compared to other parts of Mexico because they managed to have their own land. They own houses and are a little more established because there were perhaps not as many injustices against them as with other indigenous communities in Latin America. What happens here is that they are warriors, very warrior-like. Actually, a small fact– upon the arrival of the Spaniards, they resisted a lot, which is why the Zapotecs were able to preserve their cultural legacy. There is a part of Oaxaca that was not conquered and it is called “The Never Conquered”. They are in the Sierra, and they have this spirit; they are revolutionary.

LATINNESS: Looking back, what’s the biggest lesson you’ve learned throughout this adventure?

JAVIER: I’m thankful for my time in Europe because it made me connect a lot. Before I thought what I wanted was perhaps a very cliché idea from Latin America, but coming back after five years of being abroad and arriving in Mexico, to this town, made me feel like I was from here. And I know that if I go to another part of Latin America, to Colombia, for example, I’ll also feel at home. There’s a closeness that I didn’t experience in other countries; not in the United States nor Europe.

Of course, our culture makes us a little warmer and not so uptight with many things, but beyond that, we understand the cultural mix we have, we understand the struggle and the rejection of race and the origins of Latin America, both indigenous and African, as well as class… There are many classes. There’s a rejection of that denial, and it’s not a question of color or a colonized idea. There are elements and stories that unite us.

I tend to get ideas from these lived issues, such as the arrival of the Spanish and what is happening now on a social level, because here in Oaxaca, you have the opportunity to see people from almost 500 years ago. You reach communities and understand what the panorama of indigenous culture was like in this part of the world, which I find intriguing. I don’t want to make it only about the technique and design, but also the intellectual. I want to understand the person.

I’m not indigenous, but I grew up in this Latin land. I see that in the Dominican Republic there’s a strong cultural absence. We’ve already lost many values that existed before. Here, in Oaxaca, they were able to preserve something. It’s intriguing to see that this is how we were, this is how it was. Now we are something else; we are a mix.

LATINNESS: And aside from the techniques, what have you learned from the artisans?

JAVIER: They are very humble people, in every way possible. The greatest wealth they have is the humility before their work, before their technique, before the great ability they possess. Any of us would be strutting, as they say. You know, you see a lot in the design and art world because people who are recognized, become grand, but the artisans have the tranquility of modesty.

In the end, I realized: ‘Who am I to be saying that this is my work?’ Which is why I always speak of our work as something that belongs to us. It’s neither mine nor the artisan’s. If it belonged to anyone, it belongs to the culture. It’s important to understand that there were people before us, both in our family and in these communities; they received the technique, but they did not create it. The same thing happens when you take references or ideas; you did not give them life, it was nature or the circumstances. Who am I to be putting labels on these things?

LATINNESS: Tell us about the name of the project. What does Rrres mean?

In Catalan, without the first two R’s, it means nothing. They say, for example: “Thank you” and they respond “Da res” or “No pasa res”, which means, you’re welcome or it’s nothing. I didn’t want to put emphasis on the name, nor wanted people to think, “why did they name it that?” Most people don’t even know how to pronounce it and have trouble identifying that part, but it’s exactly what I wanted, like this isn’t what’s important, don’t focus on it.

In any case, what I wanted to talk about is Latin America, about us as humans, about us as history. This ends up translating into simple things. For example, the sculptures are the family, the family nucleus. They are inspired by the coast of Oaxaca. It reminded me a lot of the Dominican Republic, and it translated into an issue of expression, in more intense color, in more movement. It was inspired by that, but, in the end, I don’t own it.

LATINNESS: What role do you think design plays within society?

JAVIER: I really like the Bauhaus concept, how it breaks with the Renaissance and the Baroque, because it was excessive. To understand that it goes beyond an aesthetic thing; it must be for the benefit of the people and be of help. Someone with fewer resources can build a house with these standards, because that possibility is already there: it is not necessary to make a building with 50% more materials, which was the standard at that time.

Based on that concept, I think (design) has a social role. And not only with tangible things, also with ideas. It has to do with being able to help and develop pieces that are within a system in which everyone benefits. I feel that design can go a long way, especially in solving problems that have arisen as a result of inequality.

Although we are not diplomats, we do not know how to make treaties, and in occasions I feel impotent in the face of many injustices, and I feel I do not have the soul to go out and see them there, but at least I know that from the design perspective, I can try my hand at helping.

LATINNESS: What future plans do you have for Rrres?

JAVIER: I have a fixation on Colombia, and I want to go to different parts of Latin America. Maybe I’ll go back to the Dominican Republic to do something, and create treasures from every place I can go. Maybe in the future, when I have a consolidated team running my studio.

For now, in the near future, I plan to continue developing projects here, especially because I like that proximity. I love that I can be next to the technique and dedicate time to it. This allows incredible things. We can still take a lot of advantage of the work here.

I’m going to start with the backstrap loom, which is a beautiful traditional pre-Hispanic technique, and one or two more before leaving Mexico.

LATINNESS: You’ve accomplished a lot thus far. Do you still have a dream to fulfill?

JAVIER: In the near future, which is no longer related to Rrres, I’d like to develop a type of foundation that helps artisans with design through training so that they can create variations of their crafts, and go out to sell them at the local markets.

Now everything is uncertain, but before the virus, there were mercados near their communities where they could go to sell their crafts. Often, they had no idea what to sell. They make the same as all the others, so they don’t end up selling anything. In addition to training, I’d love to help them create a kind of catalog to offer to certain clients, such as hotels, so that they can sell objects such as plates and pots.

The idea is to work cooperatively. To constitute a team in which I help by showing them what they can implement to improve and sell, and in which they are in charge of developing the products, because I would only dedicate myself to sharing the know-how. I know this is lacking and if we achieve something like this, we can increase the profit for artisans by thirty to forty percent.

It is a type of dream. Sometimes I think that I can contribute more to these people, but I don’t have the capacity to carry out all that it entails. The idea, in the end, is a philosophy of openness to help, to not be jealous with what you have been given. That’s how it is. I arrived in Oaxaca and had access to things that were already established; I made the effort to be here, knock on doors and enter, but that was there, and they shared it with me in a certain way.

So, I’m still in that mindset of openness to help anyone. We have to do more in these times that we live in now, give each other a hand and put aside selfish thoughts of me, me and me, and this is mine. It might never be enough, but making our contribution is more and more necessary each day.