COFFEE WITH

JAVIER SENOSIAIN: “ARCHITECTURE IS A REFLECTION OF THE TIMES, AND IT’S SURE TO CHANGE”

Name: Javier Senosiain

Profession: Architect

Place of birth: Mexico City, Mexico

Zodiac sign: Taurus

Instagram: @javiersenosiaina

LATINNESS: Javier, what led you to architecture?

JAVIER: While I was studying in high school, I didn’t know what profession I wanted to pursue. I was between Civil Engineering or Architecture, so I took a test, and it resulted that my vocation was more focused on the latter. Although I came in with the idea of setting up a supply store, as time went by, I fell in love with the profession.

We were fortunate to have the famous Mexican architect and painter Mathias Goeritz as a teacher during my first year, and that motivated us a lot as students. At that time, we did social service in a town and, according to their needs, each of us proposed a theme. At the end of the degree, for the thesis, I proposed a sports cultural center. Although I started designing orthogonal spaces, there came a time when I realized that sport is free flowing, so I changed the concept to curved shapes and organic spaces.

From that moment on, I was focused on curved scenarios. I think they are more human. At the beginning, it was a kind of investigation. Although I was doing rather conventional architectural projects, I started working on others dedicated to organic architecture, and that’s how it all started.

LATINNESS: How do you define organic architecture?

JAVIER: It is one that seeks harmony between the habitat of man and nature. According to the painter and architect Juan O’Gorman, it is one that takes into account not only the geographical conditions of the place, but also the cultural ones. Its reference is geographic and topographic, and makes an analysis of the site, the views, the environment, the orientation. I think that all of this is very important because it ensures, in some way, the communion of man with nature and of nature with man. It is a binomial that has always occurred, even since primitive times, but which became more relevant in this era of pandemic when we yearn for nature. We are giving it the value it has, and sometimes we forget that.

LATINNESS: How do you see the future of organic architecture post-pandemic as we seek a greater connection with the land?

JAVIER: Architects are going to have nature more in mind. I remember that shortly before the year 2000, at the end of a talk I gave, the question came up: Where is architecture going? At that time, there was a tendency towards the natural and the human. Why? Because in the last fifty years, more nature has been destroyed than in the previous fifty thousand years, and man has not been taken much into consideration. In other words, more attention was paid to the land, buildings, loans, deeds, permits and a series of rituals, but almost never to humans.

Time passed, and today, I can tell you that yes, in general, architecture is a reflection of the times, and It’s sure to change.

LATINNESS: Interestingly enough, we discovered organic architecture through Instagram. What are your thoughts on creating these very private, discreet spaces that eventually become famous in the age of social media?

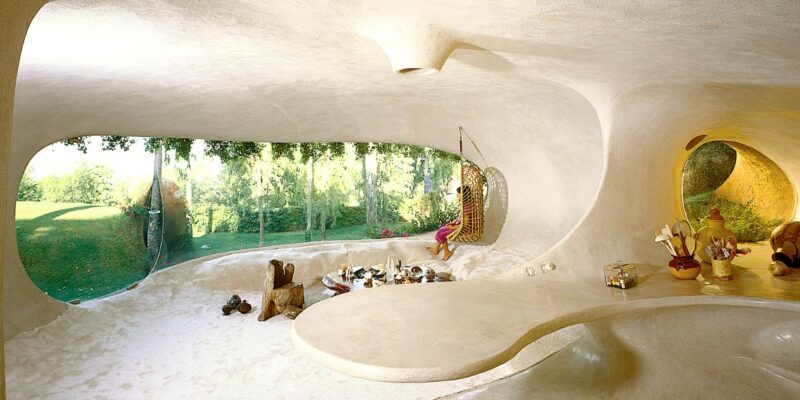

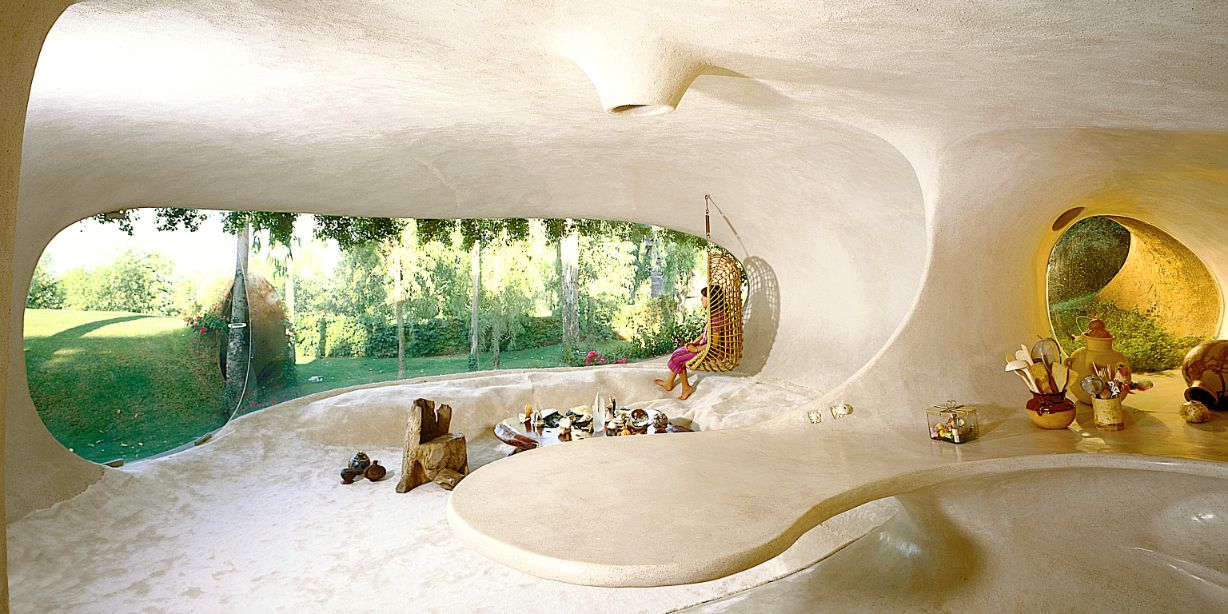

JAVIER: Yes, now they have a lot of exposure. This whole Instagram thing is amazing. Magazines, newspapers and other news media do not have as much reception as the digital ones. It strikes me that the Casa Orgánica (Organic House) is better known now than it was in the mid-eighties. It’s been 35 or 36 years since it was finished, and today it is more ad hoc, more fashionable. Back then, there was not as much ecological awareness as in the current era, and that makes me think about how much the world has changed in these last three decades. Although we continue to have a negative acceleration in terms of pollution problems, there is more awareness, which is already very convenient.

LATINNESS: In this sense, you were quite a visionary with your work…

JAVIER: It was more of a concern. I wanted to integrate grass on top of the house, to create a garden on the roof that offered advantages with respect to temperature. It was not something new. In Mexico, Carlos Lazo had built a house with a garden upstairs in the fifties, and the intention, the idea or the objective, was to make spaces adapted to man; to see man as an animal, to return to the origin.

Gaudí used to say that being original is going to the origin, that is, the word original comes from origin. I think that at this time we are going to have to go back to the origin; even regionalism, since current globalization has hurt us a lot. All this intercommunication between people and materials in the world, the fact that many things come from China or other countries just as far away, these long journeys, causes more pollution. It would be good to go back to the regional, to try to see that the food we eat daily is physically close, as much as possible. Javier Vázquez commented that progress is setback and setback will be progress. I think, in many respects, we are going to go back to our origins.

LATINNESS: What does your creation process with a client look like? Have you received any surprising requests?

JAVIER: Lately they’ve written to say they want a house shaped like an animal, a dolphin, for example, and I have to explain that it doesn’t work that way. Of course though, it’s very important to understand the needs of the client and the requirements of the site. So, first, I find out what they want, and then I do an analysis of the site.

I follow a creative process that, at first glance, may seem very cold. I start with an investigation that is synthesized and summarized. Then comes the most interesting and mysterious thing: the architectural concept. Once defined, the following is the preliminary project and, later, the architectural project, which reinforces the concept. Finally, I develop the executive plans and return to the research at the beginning, which usually includes four bullets.

The first step is to define the needs. There is an architect in Mexico, Adrián Chaves de la Mora, who explains that this is the key to everything. The initial thing is to group them, either in services, in public and private areas, etc., and make this clear, concise and precise. The second step is the analysis of the site: the terrain is synthesized, the orientation is set, the contour lines, what is in the environment and some views… I dare say that eighty percent of the time, this step gives the architectural concept.

LATINNESS: We’re intrigued by the names of your houses: Peanut, Flower, Shark, Whale. Can you tell us a little about how you name them?

JAVIER: They never appear from the beginning. Tiburon (Shark), one of the first constructions, is an extension of the Casa Orgánica. When the structure was almost finished, the construction workers, the masons, named it that way, because it had a curved window, and it looked like one. So I said, well, I’m going to put shark signage on it, but usually it is not born a priori, but a posteriori. It happens similarly to when you see the clouds and try to find a shape for them, that of an animal or a plant. Well, the same happens in organic works.

Many times it begins to resemble an animal, although we do not start from a specific animal form; people find the similarity in it, and lately, we have the luxury of reinforcing it with something.

The same happens, for example, in Mexico, with orthogonal works. There is a project by Agustín Hernández that they call ‘The Washing Machine’ because it is shaped like one. Also, one by Teodoro González de León called ‘El pantalón’ (The Pant) for the same reason. People start baptizing them, and the names stick. When they are orthogonal, they look like objects, while organic shapes resemble living things.

LATINNESS: Is there a project you’re most proud of?

JAVIER: I loved Casa Orgánica. It was the first organic project we did, and we spent a lot of time on it. The investigation took us three or four years, maybe more. The project took between a year to a year and a half, and the work lasted another four years.

Frank Lloyd Wright always said: “My best work is the one I am currently doing.” However, my teacher used to insist that, like with children, they are all loved equally, even if they are different. Although I think that sometimes, unconsciously, there are parents who lean towards one. The works are a bit similar, but definitely Casa Orgánica is the one that I have the most affection for, not only because of the time that was dedicated to it, but also because we lived there for 25 years.

LATINNESS: Did you create it for yourself?

JAVIER: Yes, we built it to live in. When we returned from our honeymoon, we went straight to the house, and we stayed there until my daughters entered college. It was far away, so we moved to an apartment closer to their schools. The Casa Orgánica is still there, and is open to the public by appointment.

LATINNESS: You did a retrospective at the National Museum of Architecture. What does this achievement mean to you?

JAVIER: A great satisfaction, and it was very important for the firm. Many people attended and others discovered our work through that exhibition.

LATINNESS: You are a university professor. If today you had to teach a class to future architects, what do you think would be the most important current issues to address?

JAVIER: The objective of architecture is to solve the needs of the human being. Unfortunately in schools there is always a lot of academicism, and there is more talk about the function. Students and teachers are limited when it comes to organic, because they tell them that it will be very expensive, that it is structurally difficult to do and they put a lot of ifs and buts. So, it is essential for those future architects to know that when they are planning, the most important thing is their project.

I remember that back in the eighth semester we had three proofreaders; each one independently told you everything you needed. I tried to channel that, to guide it and, well, it worked for me. I would tell them that the key is what your project asks for, what it wants, its design; more and more I am convinced of its emotional and psychological function. It is essential.

Regardless of the basic and elemental needs of the human being, such as eating, cooking, sleeping, talking, etc. I think that psychological functioning is as important as the other. In fact, form and function must be one, not so much that form comes from function. It is not so easy when it is projected, but I feel that the essential thing is to have a good space in which you are comfortable, with a good view, good temperature, good ventilation, good lighting, but that also makes you happy. There are many buildings that have a function; some were old libraries or houses and later became a museum or something else; the secondary function usually suits you better than the original. Why? Because sometimes everything is so functional that it doesn’t work.

LATINNESS: We’ve spoken with many creatives, and often, the topic of creative block is mentioned. Have you experienced it during your career? And if so, how do you confront it?

JAVIER: I think so, but usually, and especially lately, if I follow the creative process, the concept comes out naturally, a bit embryonic. Although there is this blockage, it flows, and if it happens, it is because there was some flaw in the essence, in the investigation.

The architect Frank Lloyd Wright would tell his disciples to create the concept in their mind and not to sit on the drawing board with the stadiometer squares to be projected. Today, it would be something like: “Don’t sit in front of the computer to project; keep that concept in mind, and try to continue the gestation”. When it is clearer, a sketch can be made, and like with most sketches, the first one is very simple, a few lines.

LATINNESS: What project are you working on now?

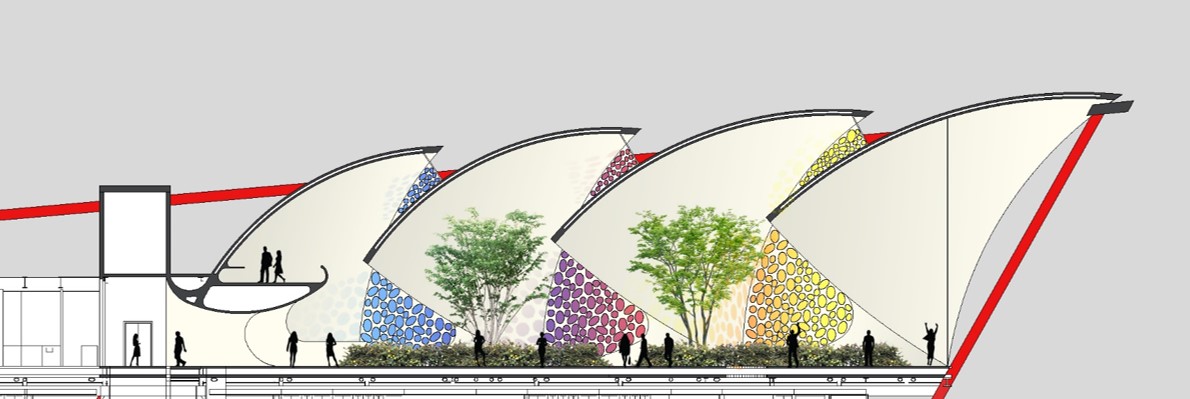

JAVIER: The Quetzalcóatl Park, a long project, which we’ve been working on for a long time. We’ve been at it for 10 years. We are in permits, and are still doing some sketches.

This began with the Quetzalcóatl Nest, which has ten departments. Construction started 15 years ago, and was completed about 8 or 10 years ago. Currently, two are rented through Airbnb, and the others are private rentals. Alongside, there is some land that the owners were buying and began to make gardens and water mirrors. There came a time when it was possible to build an ecological park.

There is a lot of work that is not seen, which is administrative and negotiations. Today, we already have the master plan for the park. The idea is to enter through the back, where there are some pantheons, get to a parking lot and from there go to Quetzalcóatl’s Nest. The idea is three kingdoms: the animal kingdom, where the intention is to put a farm with land animals (maybe a cow, a deer, etc.), flying animals (a very small aviary) and water animals (a very, very small aquarium). The mineral kingdom, which is a cave where you can see the minerals, and the vegetable kingdom, where there is a greenhouse, a garden of vegetables, one of medicinal plants, another of desert species, and finally, one of beans, broad beans and corn. We’re working on it.

LATINNESS: Is there a project you still dream of creating?

JAVIER: Of dreaming, no, but I would like to make a development with a view of the sea and a church. Although sometimes I say: “I no longer want cheese, but to get out of the mousetrap.” For now, with the Quetzalcóatl project we are very entertained.

Images courtesy of Arquitectura Orgánica.