COFFEE WITH

STEPHANIE BONNIN: “FOOD PERMITS YOU TO SAVOR A FEELING THAT TASTES LIKE HOME”

Name: Stephanie Bonnin

Occupation: Chef, Founder of La TropiKitchen

Birthplace: Barranquilla, Colombia

Zodiac Sign: Cancer

Instagram: @latropikitchen

LATINNESS: Stephanie, can you briefly tell us what led you to where you are today

STEPHANIE: I’m from Barranquilla, Colombia, I live in New York and I’m married. This started accidentally in the sense that, I don’t know if you have ever lived outside of your country, but when you’re an immigrant -and I always say this- you don’t really belong anywhere. So, you always feel the need to connect, and you find different forms of doing you. For me, it was through the kitchen. Food provides a comfort that a lot of other things can’t, to savor something that tastes like home. I started very informally, because I moved to New York and started creating a story through my small community. When you’re in a situation where you’re far from home and from your family, you always try to create your own family, or your community. And that’s how La TropiKitchen started, trying to find a way to bring all these people together, I began cooking Colombian food for everyone. Sometimes my husband would complain and say: “Why am I feeding 20 people at a time?” It was my way of feeling close, of feeling like part of a family. In New York, the winters are really cold and complicated.

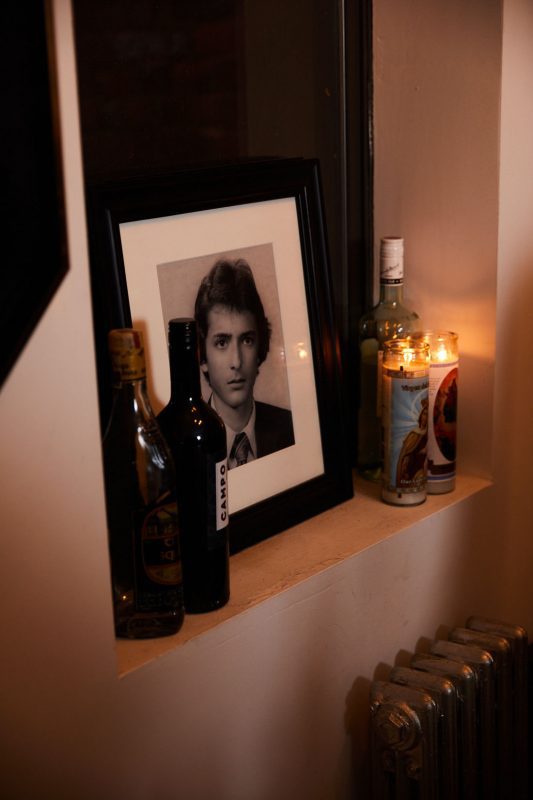

The project is called La TropiKitchen because I have all these clay pots and pans hung from the ceiling in my kitchen, so my friends would say: “Let’s go to the TropiKitchen!” I never even gave the project a name. In 2014 my father passed unexpectedly, and I hadn’t seen him for two years because I was in the process of filing for residency. At that moment, I was working at a creative agency in New York, feeling like when the city absorbs you and you’re in a super toxic industry, above all in fashion, and you’re attending all these parties. It hit me really hard when I realized I had become someone else, and my father was sick and I had the obligation to go see him. I went to visit after almost four years of not seeing each other, and many things had occurred in my life since then. I was studying Law, but never graduated, and when I came to the United States, a lot of things changed. I became an empowered woman who felt independent. So when I returned to see my dad, it was difficult to accept that he was sick, and I was a completely different person than when I had left. We spent time together, and it was a beautiful moment where my dad finally told me that I had to do what made me happy and live my truth. I returned to the United States and started to rethink everything. Was I really happy with what I was doing? Working as an office manager at a creative agency where I was paid little to nothing, surrounded by people who didn’t actually care about me?

I experienced an emotional crash and a serious identity crisis. My father died two weeks later, and it was a cathartic moment. For one year, I entered a deep depression, and discovered that through the kitchen, I felt present. When you’re depressive, you think about the past a lot, and I realized that the only moments in which I felt 100% present were when I was cooking. This whole story is so that you understand how I ended up working as a chef.

LATINNESS: Prior to this, did you have any history with cooking or Colombian cuisine?

STEPHANIE: With this whole situation, I felt a need to connect with where I come from and with who I am. I found myself through gastronomy, but then said: “In reality, I want to know what the real Colombian cuisine consists of.” In the Caribbean they always sell you rice and beans, and all these cliché dishes, everything is fried fish. “It can’t be!” I thought, so I told my husband: “I’m going to Colombia.” My father was also an adventurist, he would leave and spend days with indigenous communities in the Sierra, and so I started to connect with that idea of him, and went to visit communities, investigating and trying to understand the true Colombian cuisine. My project changed drastically through this experience. At first, it was about good food and fun with friends who would eat for free at my house. Then, I began receiving calls asking how to make this or that, so I made instructional videos explaining how to make fried plantains, coconut rice, etc. Then at one point, I realized it went much deeper than that, which was when I decided to visit and learn the recipes firsthand from all these carriers of our traditions. I decided to study culinary arts and continued investigating. I’ve traveled all over and have a personal relationship with tons of grandmothers from all parts of Colombia- I have a lot of grandmothers and aunts.

LATINNESS: Are you the first person in your family to work in the culinary field?

STEPHANIE: Yes, my mom is a terrible cook, and my grandmother from my father’s side didn’t cook either, but she did go to the market. As a little girl, I loved going to the supermarket with her, and there was always Mercedes, our nanny. She passed away three weeks ago, and my life flashed before my eyes because she was my first connection to cooking, transforming food, and above all, showing love through food. She’d sit next to me and say: “Eat or you won’t grow”. I’d sneak in the kitchen, and she’d say: “Come, help me do this, help me do that” while my grandmother would shout: “Get out of the kitchen!” Of course, it was hard for my family to accept that I wanted to be a chef. My grandfather would tell me: “What? You studied law. Graduate, that’s what you need to do.” But I would insist: “No, I’m not going to live a lie.” What I love is cooking, and I feel very fortunate that there is a lot of respect for my profession in my present reality, without discrediting the work of many carriers of tradition and many women who sacrifice being with their children to take care of someone else’s children, yet still give them love. So she [Mercedes] was everything.

LATINNESS: With all this education and experience, how did you arrive at what today is La TropiKitchen

STEPHANIE: Well, after that, I worked at Cosme, Enrique Olvera and Daniela Soto-Innes’ restaurant. At the moment, Daniela is considered one of the best chefs in the world. Here I understood that we can elevate our cuisine. I live in new York, and there are people who still question why my ajiaco costs 20 dollars. It was beautiful to live this experience and see how someone can honor their culture and its gastronomic legacy, and to understand the Mexican cuisine. You can get a taco on the streets of Mexico or of New York for basically nothing, but they have managed to prove how it can be delicate and high-end, and you can elevate it. It was my motivation to understand that I could also achieve that with the Colombian cuisine. It’s been a process because I am trained in fine dining, but by being in New York, I’ve realized that a lot of simple, comfort food just doesn’t exist here. Going back to ajiaco, when it’s freezing cold and snowing, all you want is an ajiaco, and to know that I can’t find it here reinforced that fine dining as I know it, in reality, wasn’t my calling. It was actually recreating all these important things that make us feel at home through nostalgia, and to be the most authentic and sustainable possible. That’s what La TropiKitchen is, and all this that I’m explaining occurred in the past five years.

LATINNESS: What was the most important lesson learnt working with Daniela Soto-Innes at Cosme?

STEPHANIE: Wow! She is younger than me, but is so admirable because we come from very macho cultures, where, unfortunately, oftentimes when I visit territories, the men in the communities don’t respect me because I’m a woman. So here is this lady who is about to turn 30 (or maybe already did) and is a total boss, she runs an operation in a city like New York, and can be creative without letting a single detail escape her, obviously for me was a huge motivation to achieve the same. When Daniela entered the kitchen, it trembled. Her work ethic is so admirable because, at the end of the day, one works in these restaurants, especially when you are entry level, and it’s not like they’re going to put you in the line and let you do things, at all. You learn about the culture, the organization, how to be clean, how to manage the process, and Daniela is incredible in that sense. I feel so honored to have seen her shine in that kitchen, because, as a woman, I can do it as well, and I think that is what is most important.

LATINNESS: In five years you’ve accomplished the dream of so many: to participate in Smorgasbord and receive a feature in The New York Times.

STEPHANIE: Yes, three years ago I was in culinary school, two years ago I was working at Cosme, and last year I was selling tamales at Smorgasburg. After that, I started these clandestine dinners at home trying to tell a different story about Colombia aside from what people know. So many times people say: “Oh Colombia, coke and I don’t know what,” and I’m always like: “Oh really? Well you know something, I’m going to show you what coke is, but I’ll show you through our ancestry. Here, drink coca tea.”

I decided to create a space for educating people, because when you’re a victim of these things and of racism, well, the people aren’t always at fault, because that’s what the media has taught them. I felt the need to re educate and create my small dining area to show images of all the people, because the tradition is not mine, it’s all of ours, the credit does not belong to me. It is always super important to tell the stories of all these people and to re educate, because we are a beautiful country, one that has fought for many things that are worth knowing and paying tribute to. I started these dinners at home, and one day I received an email from The New York Times requesting to eat here. I couldn’t believe it. I asked my husband: “What is happening?”

LATINNESS: How do your clandestine dinners at home work?

STEPHANIE: It’s almost impossible to have a restaurant in New York, it’s extremely expensive, and so considering it with my husband, we thought: “ So do we go into debt or what?” So I said: “No, I’m going to be like these Colombian women, who, if they don’t have the money to send their kids to school, take a pot out on the streets to sell, or build a cafeteria in their living room at home.” I was empowered by this idea of all these women from whom I had the opportunity to learn firsthand about our gastronomic tradition, and I created a dining hall. It began with friends and family, and then, it began filling up with friends of friends, and friends of other friends, and that’s how the girl from the Times arrived.

LATINNESS: They say a write up in The New York Times can change your business overnight. Was this the case with La TropiKitchen?

STEPHANIE: I was in Colombia when the Times article was published. Like a proper barranquillera, when I got married I told my husband that I would marry him on two conditions: that I never miss carnaval and that maternity is my decision. I never miss carnaval.

When the article came out, everyone wanted to come eat at our home. The day it was published, the emails came flooding in, and people would write: “I love your story!” The sweetest email we received said: “My wife is pregnant, she’s Colombian, and she’s going crazy. She keeps threatening she’s going to leave me because she’s bored, that the food here doesn’t taste like anything. Please!” You can’t even imagine, but then suddenly Covid happened. I was going to study Innovation at the Basque Culinary Center, which had recently accepted me, but Covid changed everyone’s plan. I returned to New York, and we were all locked in. As I’m sure you’ve noticed, I can’t keep still nor silent, I constantly need to be active. So, I said: “I’m going to start delivery!” I started making what they call a corrientazo in Colombia, a sort of daily menu, and took orders on my website. People would order, and I’d go out in my Fiat 500 to deliver the food all over the city.

LATINNESS: What are your thoughts on the future of pop-ups and restaurants in general?

STEPHANIE: So people started slowly leaving their houses and doing things on their bicycles, and I began meditating on a fried fish dish a friend had asked me to make. I thought: “Fried fish [in Colombia] is usually sold by a lady whose husband is a fisherman and they have five kids, and she has a plantain tree in her backyard. So she sends her husband to catch fish, and later sells it in order to sustain her family. Ok, so I’m going to do the same!” And that’s when I set up a pop-up from the front window of our home. We set up the stand in Brooklyn and told this narrative of all these stories of resilience, of people in Colombia who do what they can to survive.

Every two weeks we’d create a different pop-up. For example, one week it was stuffed arepas with those mazorcas you find outside of schools in many places in Colombia. In response to your question, I’m not sure what’s going to happen. I feel a lot of sympathy for my colleagues who have sacrificed so much to build a restaurant and a team, and of course, there will be difficult times. Personally, I’m trying to survive and do the best I can for myself and my community. We’re all going to have to adapt to new realities, and at the end of the day, we all have to survive in some way or another. We’re human and we’re accustomed to experience changes throughout our history. It’s going to be complicated and I’m very sympathetic, but isn’t this what makes us stronger?

LATINNESS: Good point. Now, you’ve mentioned ajiaco, fried fish, arepas… What would you say is your specialty?

STEPHANIE: Clients love my enyucado, it’s crazy. I started making enyucados, which I call the Colombian brownie. I have a chocolate version, and I created a yuca brownie that doesn’t taste like yuca, it tastes like a brownie and it’s gluten-free.

I love when the American girls say: “Can I have more enyucado?” It’s really something special because any plate we create comes with an educational process, and people can identify what it’s made with and why we make it. My favorite dish will always be the tamal because it is the perfect element to tell the history of Colombia’s miscegenation. Even from a sustainability point of view, it is perfect because it packs itself, you don’t have to use plastic, it’s portable, it’s like the traditional tupperware. I always tell people the tamale was the first tupperware! It’s delicious and involves an entire family because making tamales is a familial process, so it tells a story of family union, of celebration, of many things.

LATINNESS: In your opinion, what are the principal obstacles today for the Latin American cuisine.

STEPHANIE: One is the sense of belonging on behalf of all of us who belong to this culture, because we were raised to think that fine dining is Italian or French, etcetera, and having that sense of belonging to what belongs to us. Just try making an egg arepa! It’s more difficult than laminating dough to make a croissant, for example. Another one would be the value we give it, because people are accustomed to think of our food, regardless of how artesanal it may be or what it tells about our culture or our history, it is always cheap.

Of course, there are people who are trying to survive and do not value their work. They’re going to work and earn what is necessary to feed themselves. There is a lot of inequality in that respect. When I try to make a bread roll like the palenqueras in Cartagena do, I’m grinding, I’m scraping and I’m left without knuckles, and I think: “WOW! How can these women sell these for 1500 pesos?”

LATINNESS: What flavors remind you of your home in Barranquilla?

STEPHANIE: Coconut for me is Barranquilla. Barranquilla is coconut. Although, I’d say this might be something personal because I love enyucados, I love coconut rice, I love coconut candy, I love coconut water. I cook everything with coconut oil. It is almost impossible to describe a single flavor that represents Barranquilla, because Barranquilla is, essentially, a melting pot, much like New York. People from all over the world arrived in Barranquilla in search of opportunities, which is what makes it so special. To identify only one flavor is difficult because there are a lot of Arabs, Italians, people from the interior of Colombia, but at the end of the day, what we share as barranquilleros and as the Caribbean, is coconut.

LATINNESS: What is the most important ingredient in your cooking?

STEPHANIE: Love, because I think you can transmit that. In realty, when I say I’m a witch, it’s only because my power is alchemy, I transform elements. All of us are energy, which is why, personally, the principal ingredient is love. When I need to cook, I tell my husband: “Pablo Bonnin, I have to cook 40 cakes today, please do not even look for a fight!” I have to say that because I will not cook when I’m in a bad mood or not feeling well, that’s just how it is for me. I think this is what makes my cooking so special because people can feel it. My answer might sound cliché, but that’s how it is.

LATINNESS: Have you considered La TropiKitchen’s future post Covid?

STEPHANIE: If there’s anything our window has taught me, it’s that this is the type of operation I want. I want to get to the point where I can combine what’s happening now and that people can enjoy a delicious tropical juice in the summer or a Colombian coffee in the winter or hot chocolate from the Sierra. To create channels of distribution for Colombian products on a small scale here in New York, but also have a small diner where my Mesoamerican friends can have a space to cook. That is what is important, that those stories

can be told by them, as well. Because as much as you want to manage an operation like Mesa Franca, which is my favorite restaurant in Bogota, or like Leo, which is so rooted in the territory, it’s impossible for me, but what happens if Mesa Franca comes here, with all of it’s magic and beautiful things? That is the project. That’s what I want.