Julio Kowalenko and Rodrigo Armas, founders of Atelier Caracas.

COFFEE WITH

ATELIER CARACAS: “UNDERSTANDING A CRISIS AS AN OPPORTUNITY FOR CREATIVITY IS CRUCIAL”

Name: Julio Kowalenko and Rodrigo Armas

Profession: Architects, Founders of Atelier Caracas

Nationality: Venezuelan

Zodiac sign: Leo / Sagittarius

Instagram: @ateliercaracas

LATINNESS: Julio and Rodrigo, do you remember the first time you were amazed by architecture?

JULIO: Yes, I was surrounded by a rich tradition of artists and architects in my family. My uncle, Julio Maragall, is a Venezuelan architect and sculptor who played a significant role in shaping my early fascination with architecture. He designed a tower which houses both his and my mother’s offices, and that holds a special place in my memories.

I have been visiting that building for as long as I can remember, and I could always sense it was different. It’s known as Torre ABA, and our second office was located there, and although it lacked windows, the building boasts a remarkable atrium for the city and features a massive sculpture by Carlos Cruz-Diez. It has a distinct relationship with the cityscape, setting it apart from the conventional constructions typically found in that area of Caracas.

That place left a lasting impression on me because I always perceived the building as a colossal toy, with a friendly aura.

RODRIGO: My fascination with architecture emerged during my time in school. I had a natural inclination towards technical drawing, and I quickly grasped the possibilities it offered in the field of architecture.

As I approached university, my interest in architecture intensified, and I had to make a decision between studying Civil Engineering or Architecture. Although many advised me to choose the former, I asserted, “No. What I like is architecture and apparently I can be good at it.” It was during my studies that I met Julio.

LATINNESS: How did Atelier Caracas come into existence?

RODRIGO: It actually happened in a rather amusing manner. After graduating from University in 2014, I had already been working alongside my father for two years, assisting with remodeling projects in Caracas. This experience gave me some practical knowledge in construction. One day, a friend approached me with a request to design a house for him on a beach in the Adicora area, renowned for kitesurfing, located in the western part of the country.

Feeling hesitant about taking on the project alone, I thought about how Julio and I could potentially collaborate on it. Given our close friendship and shared aspirations, I saw an opportunity. Although Julio had not yet completed his studies at the time, I approached him and proposed, “I have this opportunity to build a house. What if we both manage the project together?” And so, we began pretending to have an architecture firm, although it remained nameless initially.

JULIO: We were fascinated with the idea of producing together, as well as having an architecture firm. Architecture as a profession is very fascinating. The reference image is seeing a person opening a site plan, but then you realize it’s anything but that.

We got wrapped up in the routine of meeting every day to brainstorm and design, because architecture has a lot of that; especially how things relate to humans and space, and vice versa, how space relates to humans.

We started investing our energy in that, and more jobs came almost by inertia. I mean, we’re not very superstitious, but when you invest energy into something, when you call upon something so much…

RODRIGO: Something comes out of it.

JULIO: We started receiving one job after another, and so we said, “What are we going to call ourselves? How should we organize this?” Armas-Kowalenko sounded like a law firm, and eventually we arrived at Atelier Caracas, a name that has a nice connotation and a very funny story.

RODRIGO: This is how our process began in 2015, the year in which we officially established ourselves as an office.

The architects with their Credenza design.

The Atelier Caracas office in Caracas, Venezuela.

LATINNESS: It’s a common start: fake it till you make it.

JULIO: We created business cards that said “architect” and would hand them out to people.

RODRIGO: “Look, I’m an architect,” and we were just 24 years old.

JULIO: Although venturing into the profession at such a young age is interesting. Neither Rodrigo nor I decided to pursue graduate school or leave the country.

Without getting into politics, it was a time when emigrating was the most viable option. However, we chose to stay. There was a blank canvas here because contemporary architecture was not very prevalent.

Sure, there were things, but everything was in a status quo phase. So, we found ourselves with a blank canvas, and starting the profession at such an early age has been interesting because we’ve had to hit the wall many times. It’s through mistakes that we learn. As we say here, “you start getting gray hair.”

LATINNESS: Some time ago, we interviewed a great-granddaughter of Gio Ponti who spoke about the architect’s works in Venezuela. We were amazed by the sophistication and quality of the designs that existed before the revolution. As professionals in this industry, do you perceive any prevailing aesthetics today due to the current situation in the country?

JULIO: Well, the mid-20th century in Latin America was a remarkable time. Among the nations that emerged as cultural powerhouses in the fields of architecture, art and poetry were Mexico, Venezuela, Brazil and Argentina. From Colombia, I find myself more interested in contemporary works rather than what was done in the middle of the last century, although there are great figures like Rogelio Salmona and others. But it’s worth noting that Venezuela, surprisingly, became a major force during the dictatorship period. We have an enviable cultural and architectural heritage that we can explore. It’s something deeply ingrained in the DNA of any creative individual.

Speaking of Villa Planchart, it serves as a significant reference point in our approach to architecture. It’s remarkable that this tropical architectural gem was designed by a foreigner, through correspondence no less.

It’s a house that is so successful, both in terms of its tropical and ecological aspects… We reference it not only in how it functions, but also in terms of its finishes. I mean, in the rigor that exists, from its external shape down to the forks. In the end, in a developing country like Venezuela, sustainability is the logic today.

RODRIGO: Yes, we apply that principle extensively. Our rigorous approach is precisely a result of this type of mindset, as some architects only focus on designing the house itself. We, on the other hand, strive to design—and we would love to design—every aspect within a house.

Therefore, in our practice, there are times when the boundaries between architecture and art become blurred because, as Julio mentioned, we have a passion for designing everything, from the smallest details like a fork to the overall house design.

JULIO: Well, we haven’t had the chance to design a fork yet, but I hope that opportunity will come our way someday…

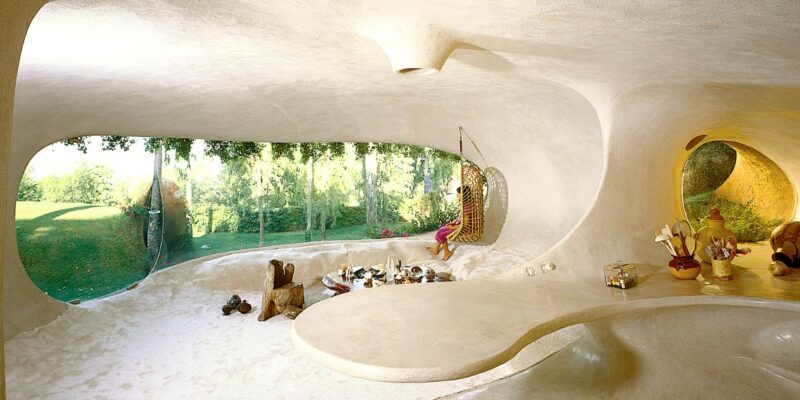

‘2020: A Spa Odyssey’, a wellness project in Caracas.

LATINNESS: Your motto on social media and your website is “This is not architecture.” What do you mean by that?

JULIO: While studying at the Central University of Venezuela, we were exposed to a vibrant academic environment. The campus itself, designed by Carlos Raúl Villanueva with sculptures by Calder and Jean Arp scattered throughout the gardens, was truly inspiring. However, there was always an ongoing and somewhat unfruitful debate about the boundaries between architecture, art, design and interior design. It raised questions like, “What is architecture? What is design?” For us, working through the lens of architecture means approaching our projects from a unique language and form of communication.

We think like architects, but that doesn’t mean we limit ourselves to solely solving architectural or spatial problems in life. People often label us as an architecture firm, to which I often respond, “We are whatever you want us to be.” I don’t want to define what we are.

We enjoy the process of design, creating images and producing things that, although rooted in architecture, allow us to explore our imagination. This mindset has given us the opportunity to receive diverse commissions and venture into other realms, such as collectible design, photography and the arts in general. We have worked on installations and various creative endeavors.

However, at the core, we still approach everything we do with a foundation in architecture. It’s quite amusing, isn’t it? To say that we don’t do architecture while working on a five-story building. It’s ironic, in a way. It’s like saying, “Don’t take things too seriously.”

LATINNESS: And now you’ve ventured into furniture design, as well…

RODRIGO: Yes, we started making furniture, but our interest in designing objects, both small and large, has always been there. In 2021, amidst the pandemic when we didn’t have a project, we saw it as the perfect opportunity to dedicate time to something we love.

JULIO: We used to make excuses about not having enough time because architecture is a demanding field.

RODRIGO: But when we found ourselves without a project, we delved into the world of furniture design. Our first piece was the Credenza, and we approached it with the same spirit we had when starting the office: “Let’s pretend we’re industrial designers now!” So we reached out to a factory in North Carolina, created prototypes and even produced renders of the designs.

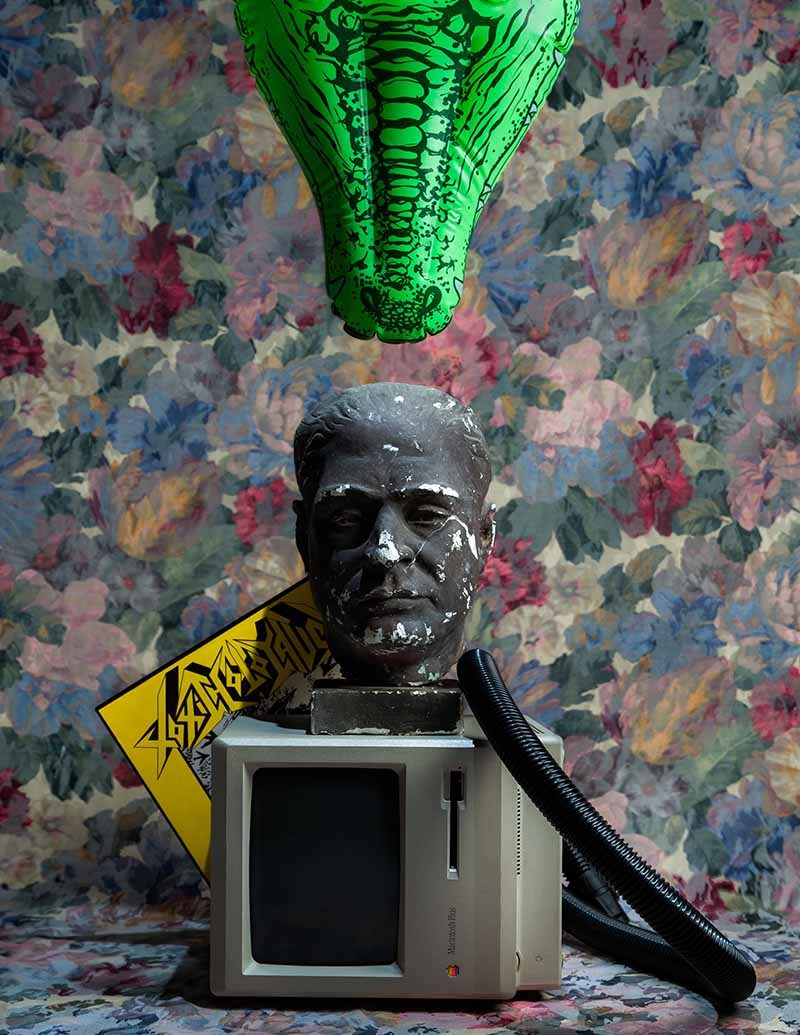

Credenza is the first furniture piece designed by Atelier Caracas.

JULIO: It was quite amusing because we had been following the work of Tom Sachs, an American artist, and found many similarities in aesthetics and references, particularly in NASA and related themes. One day, Rodrigo noticed that Tom Sachs tagged the person who made a chair for him. So he contacted the guy in the midst of the pandemic, saying, “Hey, we’re designers from Venezuela and we want to produce this piece of furniture.” We didn’t expect a response, but we received one the very next day. And that’s when the journey began.

RODRIGO: We created the prototype and were surprised to see that by the end of the year, the render of our design was published in Architectural Digest in France. We have no idea how that image ended up there or who submitted it.

JULIO: It’s because the piece has such a visually striking aesthetic. It created a significant buzz on Instagram. And from that point onward…

RODRIGO: We realized the need to take industrial design more seriously.

JULIO: Exactly, and for us, that’s architecture in the end. It requires the same level of rigor. So why shouldn’t it also be considered architecture?

‘The Parasite Project’ involved the renovation of the Colegio Integral El Ávila in Caracas.

LATINNESS: How does living and creating in Venezuela influence your work and inspiration?

RODRIGO: Living and working in Venezuela has been the best thing that could have happened to us because we have been able to pursue our passions here.

Right from the start, we were entrusted with significant projects and given the opportunity to create things that we are proud of. It has been a journey of hard work and perseverance, but everything has been positive along the way. Essentially, Venezuela has provided us with all the opportunities we have.

JULIO: Of course, some countries are more organized than others, but that sense of freedom in Latin America has given us a platform to express ourselves authentically. Moreover, if we analyze the 20th century, we can see that great artistic movements have often emerged from times of crisis. Understanding a crisis as an opportunity for creativity is crucial. When there’s a shortage of resources, we must reinvent them. When there’s a lack of work, we redefine what work means. In other words, what does architecture mean in a country where there seems to be no architecture?

This experience is like our postgraduate course: learning how to practice our profession or how to reinvent it. I wouldn’t change a thing. Unfortunately, certain events have unfolded, but we prefer not to delve into them.

RODRIGO: I wouldn’t change a thing. The fact that we went through what we went through made us more rigorous with our work and, in a certain way, reinvented what it means to practice architecture in a Latin American country, or at least in Venezuela.

We became so absorbed in our work that we hardly even noticed what was happening outside. We focused 100% on what we could do and how to execute it.

JULIO: And that also touches on the topic of why our architecture is the way it is, aesthetically speaking. It is the way it is because from the beginning, we wanted to create a sort of bubble, where people can detach themselves from what is happening. In other words, our architecture is very theatrical and fun in that sense; it is very cinematic.

We feel the need to transport people into a bubble, into another reality because we also get saturated with the day-to-day, with CNN saying that Venezuela is hell or what comes after. We don’t want to talk about that; we want to focus on beautiful things and transport people to, I don’t know, a Fellini film.

RODRIGO: And through our works, we aim to allow people who enter them, to detach themselves for a moment.

JULIO: It’s interesting because I think that’s what happens when you enter Villa Planchart. I mean, Caracas may be falling apart, but you go to that house and everything is fine. It’s very, very, very interesting, and that also happens with many architectural works in this country.

‘Fun Maze’, a playful experience for a rehabilitation center for children with disabilities.

LATINNESS: What has been the most significant project for Atelier Caracas?

JULIO: We did a kindergarten called “Fun Maze” for children with motor difficulties, a very beautiful project. First, because of its meaning and how the space was going to be used.

At the beginning, it was so ugly and had no windows! Nowadays, it has enviable natural lighting because we opened a slot in the roof, and the sun is always present; not directly above, but present.

We didn’t have a big budget, but it provided us with significant professional growth, not just as creatives but as architects. It was the first time we built a roof and faced the scale: from the size of a lamp to the relationship between a person and a roof.

Since it was our first roof construction, we did a lot of trial and error. Thankfully, there weren’t many errors, but that project is very significant to us.

Also, the Credenza, because of what it meant for the studio in terms of shifting and creative freedom. In the end, Rodrigo and I always talk to people outside of architecture because we envy that freedom. The one certain thing in architecture is gravity; buildings can’t fly.

In fashion design, cinema or furniture design, it seems like there is no gravity; there are no regulations from the municipality that will bring our ideas down. The Credenza opened that gap for us and allowed us to delve into that bubble of design. And, to be honest, with this piece of furniture, the studio got “serious”. Ultimately, that’s what we enjoy: designing.

‘Fun Maze’, a ludic labyrinth.

LATINNESS: How do you stay inspired in your day-to-day life?

RODRIGO: We find inspiration in cinema, art, fashion and architecture.

JULIO: It’s funny because we’re always looking at external things.

RODRIGO: External to architecture, but related to design. Everything that has to do with design.

JULIO: Personally, I love cinema. I adore Antonioni and Fellini. For example, I recently watched a film by David Cronenberg called “Crimes of the Future,” a morbid but good movie. And recently, we went to Salone to see David Cronenberg’s exhibition at Fondazione Prada, with his post-apocalyptic stance, that primitive future he presents, seems more accurate than the whole metaverse concept because the future, I mean, the world, is coming to an end.

As morbid as David Cronenberg may be, despite the criticisms of the film, water is running out. I mean, that seems more accurate to me. All these universes, these possibilities of science fiction cinema, are of great interest to us.

JULIO: Not because of the need to live in a bubble, but to understand how one can exist if water runs out. I mean, what does that mean?

‘This is not architecture’ is the Atelier Caracas slogan.

LATINNESS: Such as your interest in NASA, which you share with Tom Sachs.

RODRIGO: That’s right, inspiration comes from everywhere. For example, while flipping through a NASA book we have here in the office, we found a solution for a detail in a project we were working on. It’s always interesting to delve into those realms.

JULIO: Even the detail found in a piece, let’s say, by Martin Margiela. In the end, what one needs is an idea and to transpose that, which is not necessarily architecture, into the realm of architecture; that’s our job, that’s what we studied for. Because we’re not here to just copy and paste, architecture after architecture.

RODRIGO: It’s also about creating atmospheres. You can find inspiration in how a film set is lit and apply it to a project, as we saw at Fondazione Prada. For one project we’re currently developing, we drew inspiration from something we observed there. So we always take inspiration from wherever we can. From everything.

LATINNESS: What are you currently working on?

RODRIGO: In construction, we have four very important projects that are developed on different scales. Sometimes people ask us what kind of architecture we do: commercial or residential? Our answer is “we design.”

Right now, we are working on a lobby for the headquarters of a financial institution. We are also designing a significant structure for a speakeasy restaurant in Caracas. Additionally, we are in the process of designing and constructing a house and a five-story building in a relevant area of the city. This is a very exciting moment for us.

JULIO: And if that’s happening, it’s because we practice what we preach. We are transitioning from the micro-scale. Although it may sound easy to say, doing it is another story. Facing each scale with the same rigor and intensity is interesting, especially when we go to the construction sites. The lobby, for example, is my favorite project. We have invested so much energy in it! It’s almost like industrial design. We even designed the nuts and bolts.

LATINNESS: The fork is missing.

RODRIGO: Yes, that’s correct.

Images courtesy of Atelier Caracas.