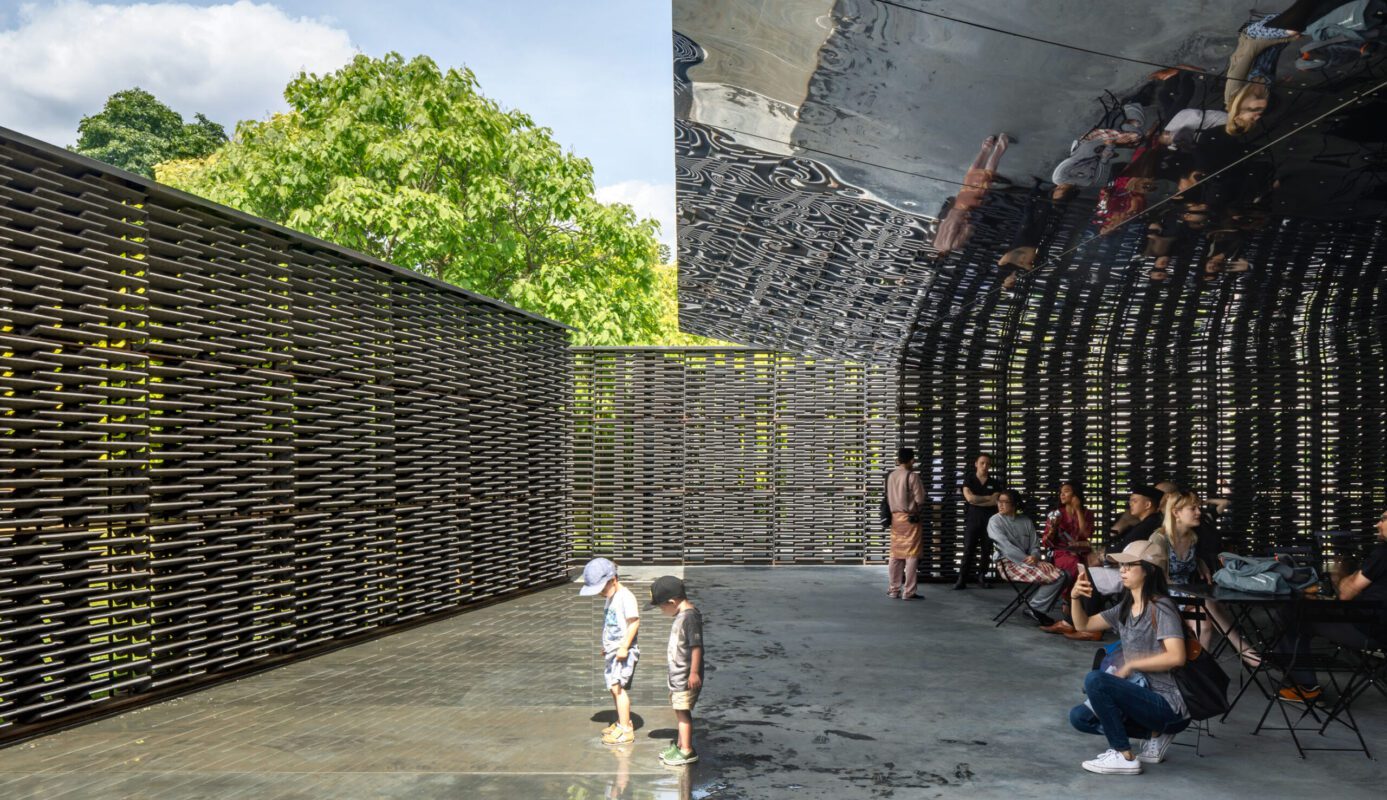

Serpentine Gallery in London, 2018. Image by Rafael Gamo.

COFFEE WITH

FRIDA ESCOBEDO: “ARCHITECTURE IS UNDERSTANDING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HUMAN BEINGS, AND BETWEEN HUMANS AND THEIR ENVIRONMENT”

Name: Frida Escobedo

Profession: Architect

Nationality: Mexican

Zodiac sign: Libra

Instagram: @fridaescobedo

LATINNESS: Frida, do you remember the first building that had an impact on you?

FRIDA: I remember very well an exhibition by Emilio Ambasz in Mexico City. It took place at the Contemporary Art Cultural Center, and my dad took me when I was very young, about seven years old.

I found it super interesting how he constructed the buildings with very pure geometries, and at the same time, integrated into the landscape. They were almost surreal scenarios with white walls and a staircase that seemed to go up to nothing. That was my first big impact.

After that, I understood that architecture could indeed be something super-utopian, imaginary. Later on, I remember also being very amazed by the Centre Pompidou, and that idea of the Leaning Square and the building with outside facilities. It was very impressive.

Boca Chica Hotel in Acapulco, Mexico. Image by Undine Pröhl.

LATINNESS: We’ve read that you didn’t always know you wanted to be an architect. At what moment did you realize this was the route you wanted to take?

FRIDA: Actually, I was always very indecisive. I knew I wanted to study some sort of art or design because I’ve always liked those kinds of things, and I feel like that’s where I tend to do a little bit better. I wasn’t very confident about studying art because to me it seemed like something in which you had to express your personality, your feelings, your ideas, while architecture is more about solving practical issues. It’s an artistic practice, but at the same time, technical. So, I decided to apply.

My mom always told me: “If you don’t like architecture, it can at least give you a good base to structure your thinking and then you can change. It’ll serve you.” So I started in this degree, and I loved it within the first week. I thought: “Yes, this is what I want to do regardless of the terrible, sleepless nights”.

LATINNESS: Let’s talk about networking. You studied in Mexico, and later went to Harvard to earn your Master’s degree. Do you feel post-Harvard networking has influenced your opportunities now as an architect?

FRIDA: Yes, I feel the school offers a lot of that. In other words, not only networking with classmates, but also with professors, and even with the resources that the universities themselves have. So, for me it was very important to have met people, for example, also from Mexico, who were studying there, but I didn’t know before, or people from other countries with whom you begin to share ideals and interests.

Later on, I taught at universities outside of Mexico, and that was also incredible because it’s another type of network and conversation. Giving talks in these educational institutions can generate invitations to competitions, which is why, in architecture, it’s important to be able to be somehow involved in academics.

LATINNESS: Being surrounded by these young talents also allows you to continue learning, right?

FRIDA: Totally. I always say that I’m going to take classes from them.

LATINNESS: What are your thoughts on the current architecture scene in Mexico?

FRIDA: Yes, and I think you can perceive it from everywhere, don’t you thinkt? Especially in the United States. People are raging about Mexico, and the pandemic helped to bring that about, like things were not so closed here. There was a lot of migration. People who had come to spend a while, perhaps as an escape from the smaller apartments or the harsh winters, began to generate another type of conversation, and many of those people ended up staying.

I think that migrations are very positive because they generate exchanges and new discourses; they create positive friction that makes things move forward. Many of those who came began to open galleries and, well, there was already a very important energy, very established galleries and newer galleries.

People with a certain purchasing power that allow those things to be maintained, made them happen. That also helped, because during the pandemic many businesses closed. However, others remained thanks to those visits abroad.

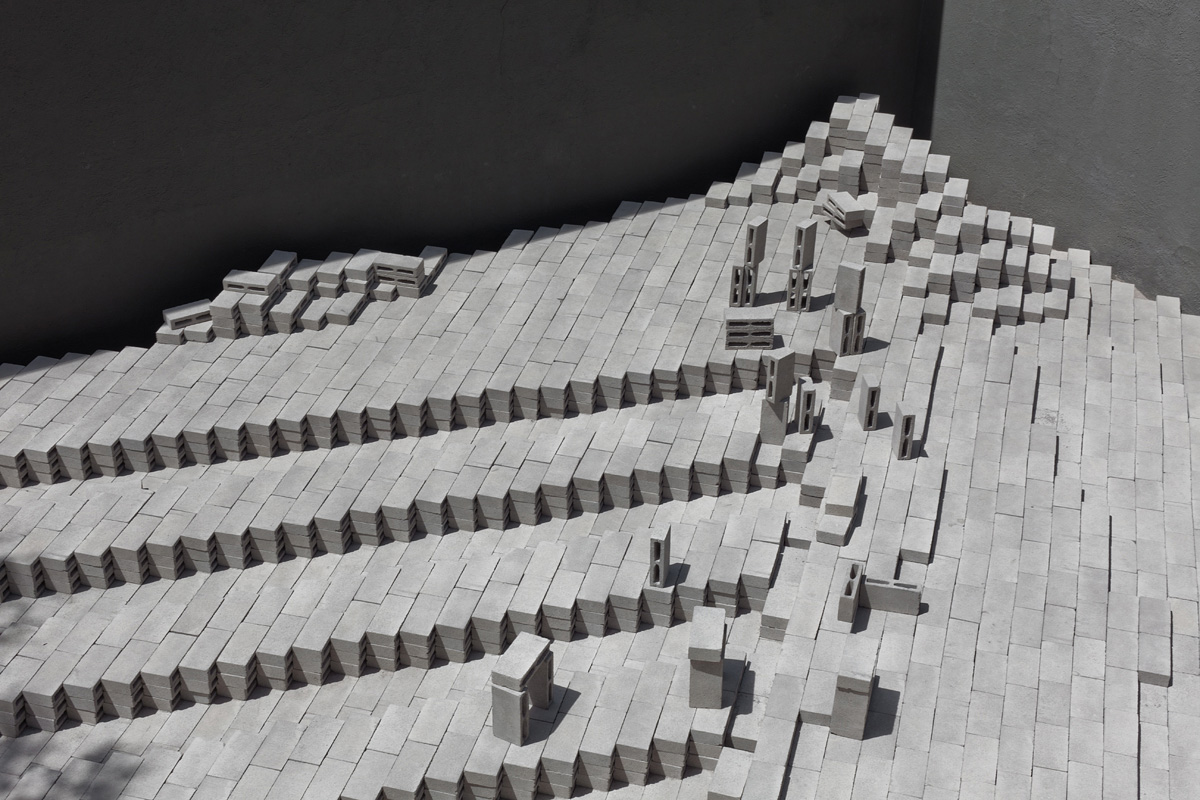

LATINNESS: Let’s talk about your work. What’s your process like in terms of defining the materiality of your projects? Do these define your construction process?

FRIDA: Yes, we almost always start from what is needed in terms of spatial organization. And once we define it —which is more of a distribution scheme—we begin to see how resources can be optimized. Because in Mexico that’s what you have to do all the time. You have to think about efficiency because I think there is no client who doesn’t tell you: “I want to do it for less money”. That’s already a given.

So, with that in mind, we start looking at what material could be the simplest, the cheapest, but also one that offers a much more interesting expression. That’s where the starting point is.

LATINNESS: Would you live in one of your residential projects?

FRIDA: Yes, of course. In fact, there was one where I said, “Should I move here?” It didn’t happen because only a few remained. But, happily.

LATINNESS: In 2018 you were the first Mexican architect to design the Serpentine Pavilion. What did this mean to you?

FRIDA: It was very unexpected. I would’ve never imagined it.

I’ve told this anecdote several times: when I received the invitation by mail it said “Invitation to Serpentine Gallery Pavilion” and I thought, “it must be the invitation to a newsletter or something like that”. I let it go.

A week later, they wrote to me again like “Hey, did you see the mail?” We had already lost time to prepare the proposal, and I couldn’t believe it, but that was how big my surprise was.

It was a process. First, we presented a project for an internal competition for which we stayed within the selection. The truth is that it’s been an incredible opportunity because it opens the panorama to other types of clients, to more important commissions. Even if it’s a very small pavilion, it’s something that generates validation and gives confidence to other types of clients.

LATINNESS: Today the big news is that you’ve been chosen to design the new art pavilion at the Metropolitan Museum of New York. We know you can’t talk about the project yet, but how did it feel to receive that news?

FRIDA: This was another huge surprise. This and the (Serpentine) pavilion have been the two great surprises of my career, especially because when we were invited to participate we were competing against four very consolidated and very important offices.

We made a huge effort. We put everything we had into those five months in which we were developing projects and thinking that we wanted to win, but also understanding that we were competing against heavyweights. And yes, it was very exciting to see that we did it.

Mar Tirreno in Mexico City, 2016. Image by Rafael Gamo.

LATINNESS: Huge congratulations. I think Mexicans, and Latins in general, feel very proud with this news. You’ve worked on museums, but also on residential projects, how do the processes differ between one and the other?

FRIDA: The most complicated are personal homes, right? It’s a commission that, regardless of whether it’s a very small or very large space, is the life project of many people. It becomes incredibly important and every detail counts. In fact, you have to understand how the ideas are going to be a projection of the personality of that family or that person.

When you face a larger commission, it may have to do with institutional issues or broader cultural representation. Then we can do a reading or an interpretation, but when it’s a housing commission, it does have to accurately reflect what the customer expects, and many times they don’t even know themselves.

LATINNESS: We’ve read that when you start a project, you confront it from a social perspective. How did you come to define this focus or style of architecture?

FRIDA: It comes from a natural curiosity, from seeing how people interact. I inherited it from my mom because she’s a sociologist, so she’s studying and observing behaviors all the time… I guess it was contagious.

For me, architecture is understanding those relationships; the links between couples who want to build a house or between different social groups that meet in a public space. Or between neighbors who can live together in a building. Also, how people see themselves projected on a building and what they identify as part of their identity.

LATINNESS: How much do you feel that your Mexican culture influences your work?

FRIDA: It’s inevitable. One ends up reflecting the context in which you develop as a person because that’s what you’ve absorbed and what you’re going to project, in some way.

I think that growing up in Mexico City stimulated me a lot and shaped how I see things, those juxtapositions, those overlaps between places that can be historical, but in which you don’t see a single story, because there are multiple in the same space or spaces where everything converges.

In other words, in Mexico everything happens in the public space: people eat, move, have fun, celebrate and protest there. Everything happens on the street, in the squares. I live on Paseo de la Reforma, which is a very important avenue in the center of the city and there isn’t a day that goes by where something isn’t happening here: marches, festivals, Zumba classes…

Museo Experimental El Eco in Mexico City, 2010. Image by Rafael Gamo.

LATINNESS: Mexico City truly is impressive. Do you have a favorite project?

FRIDA: That I’ve done? Uf! It’s like choosing a child that I don’t have.

A very important project, although very small, was the Eco Pavilion because, although it was a temporary installation, at that moment, I saw for the first time what those relationships between people and space were like and how they could materialize. That later formed many of my following projects. In addition, it was one of the first in which we won a competition, which gives you the confidence to apply to others. It was a tipping point for me, and it gave my career a direction.

Museo Experimental El Eco in Mexico City, 2010. Image by Rafael Gamo.

LATINNESS: Who have been important influences in your career?

FRIDA: I’ve come across many teachers and people in my career. I never worked for any office; I started independently and continued like that, almost by accident. But I did do a scholarship called Young Creators, a great program here in Mexico, and Mauricio Rocha was my mentor.

Listening to him helped me a lot– the importance of supporting us who were the scholarship holders, the idea that architecture is a career in which you need to have extreme patience, and on this long road, we shouldn’t forget who we are working for.

Sometimes it can be very frustrating because it’s a difficult and long career with many hours of dedication, so it’s very easy to throw your arms up and say: “Well, let me do something that will bring in money, and that’s it”. He always reminded us that this race doesn’t work that way, that one must be insistent.

Also, I remember a professor at Harvard, Erika Naginski; an incredible woman with a very particular vision of history and space, which influenced me a lot.

There were also other types of influences from colleagues and friends with whom I’ve worked: José Rojas, with whom I did the Hotel Boca Chica project in Acapulco, because I learned a lot from him. I particularly admire his way of seeing things. Now he’s in front of a gallery and no longer dedicated to architecture, but he has a very educated eye.

And other friends with whom I continue to collaborate, making projects or furniture or other things: Rodolfo Díaz Cervantes, Mauricio Mesa… there are many people who continue to influence you along the way.

Boca Chica Hotel in Acapulco, Mexico. Image by Undine Pröhl.

LATINNESS: When you work on your projects, do you also get involved in the design aspect?

FRIDA: Yes. In fact, I only dedicate myself to design. I don’t build. Building, for me, is a much more stressful discipline than architecture. The work I do is at my desk, and then I entrust the execution work to a few people who have my complete trust. Of course, I always supervise the process.

LATINNESS: And with interior design?

FRIDA: Yes. In fact, I’ve always thought that I couldn’t make a building and then have someone decorate it or intervene inside it because then I feel like I’m leaving the experience incomplete, right? When this happens, almost always, either we try to make it someone with whom we are already talking so that the ideas complement each other and then it becomes a unified experience, or we try to do the interiors ourselves. If not, I feel as if it has a double personality in terms of space.

LATINNESS: If you had to give a class to architects today, what would be the most important lesson to teach them?

FRIDA: I’d share the advice that Mauricio gave me: patience. That also has to do with being gentle with ourselves. We are at a time where we have to respond to a lot of pressure to generate capital very quickly. Each time the projects have to be done faster and be more profitable. Every time, you have to build in less time.

It’s in those moments that I think: “Why can’t we have a little resistance and say that we have to invest more time in these things?”. In fact, we should clearly explain the time it takes for ideas to be well developed. This will be reflected in higher quality spaces that last longer.

I feel like now, with the present urgency that demands doing things faster and more profitable, the spaces end up looking good for only a few years. They’re evaluated and must be replaced. So, a cycle of a lot of waste is generated, and it’s a consequence of thinking little about the process from the beginning.

Pasha de Cartier in Mexico City, 2021. Image by C129.

LATINNESS: You’ve collaborated with several fashion brands, such as Ferragamo and Cartier. Tell us about your relationship with fashion and how it relates to your work as an architect.

FRIDA: I love it. I think that the first architecture is that. It’s not just about how you’re projecting yourself to others. There is also something with the material, with the qualities of textiles and with how a garment is structured. But, above all, with how some codes are generated; in fact, a person doesn’t need to speak for you to identify the image they are projecting. I find it very interesting, and it has a great relationship with architecture.

When I received the invitation from Ferragamo, it caught my attention, because at the end of the day, it was a limited edition– only 20 pieces– and along with two other artists who I also admire, who I love and who have become friends.

It was a very fun process because I actually had to make a kind of façade for an object that you could take with you everywhere, and that has to do with how you project yourself. It’s like making the pattern for the bag. It was then about translating that idea of the façade to a smaller object. Also, a bag is definitely something you carry a little bit of your life in, all the time. So it was a very fun exercise for me.

Collaborations with other brands have been more in terms of image. We did a special intervention for Cartier, for an event with Pasha. It was a series of events that took place in different parts of the city, and we made a piece in which we deconstructed all the iconic elements of the clock, the circle and the square.

So, we thought of a cube that is divided into 12 hours and at those 12 hours we made some circular cutouts. We filled a room with these loose pieces and along the way you could find asymmetries depending on where you were looking at them from. The idea of the tour was that: the passage of time —which sometimes becomes very diffuse—, memory, how you remember it depending on your perception: sometimes slower, sometimes faster. It was a very perceptive thing.

LATINNESS: We’re curious about a New York Times article that recently called you a “woman of color”. How do you handle this kind of message that happens to all of us being Latinas?

FRIDA: I feel like there’s an obsession with trying to classify us, right? To say: “this person is this”, “this person is that”.

I understand that I was born in Mexico City, but because I’m from there, can I be considered a person of color? Yes, I have roots of color, and it’s also a matter of how people identify themselves.

I think it can be problematic for people of color who have other characteristics. Probably when reading: “Well, there is already a woman of color doing a project like this”, they feel that I really do not represent that group. I can definitely understand and empathize with that.

But on the other hand, I think it has to do with the idea that someone else is building something. It’s an opportunity to say that we Latin women can take on this work that before was only done by men of a certain age, North American or European. That the doors are opening, and that, at the end of the day, it’s about joining forces and there are more and more opportunities for everyone.