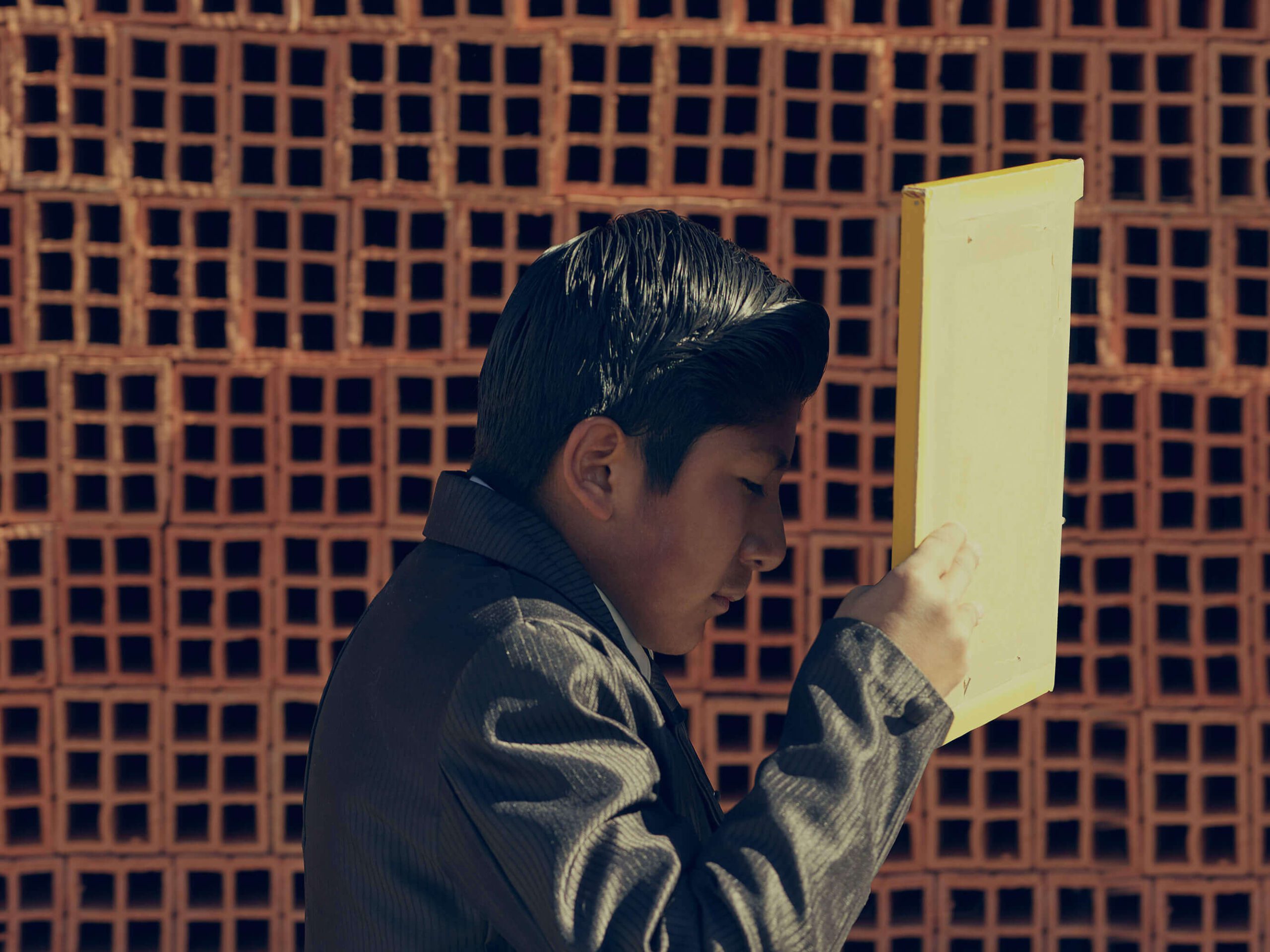

From the series ‘Cold Road’ photographed in Bolivia.

COFFEE WITH

NICK BALLON: “PHOTOGRAPHY WAS MY FORM OF COMMUNICATION IN A CONTINENT I KNEW VERY LITTLE ABOUT”

Name: Nick Ballon

Profession: Photographer

Nationality: British-Bolivian

Zodiac sign: Sagittarius

Instagram: @nickballon

LATINNESS: Nick, what’s your nature as a photographer?

NICK: It starts with observation, and I like the idea that my introverted character is so drawn into a subject matter that I have to go and ask them, even if I don’t know them or don’t speak their language, but can communicate through other means. The pitch is so strong in what I’m trying to achieve that I have to ask to have that picture taken, or at least approach that subject matter.

I love that human intervention part where it’s something inside of me which is actually making me do this. Naturally, as somebody on the street, I would probably be less drawn to stop and talk to a stranger, but as a photographer, it happens. I’ve been doing it for years. If I’m in a place and I see somebody I want to photograph, that’s something I can’t help. It’s a subconscious kind of message in my head that makes me go and take that picture.

LATINNESS: Do you prefer photographing people you know or strangers?

NICK: My earlier career started off very much deeply rooted in editorial portraiture. I was sent very regularly to photograph celebrities, politicians and people of importance. I had really been trying to shoehorn my career into working for Sunday supplements and the editorial market where I thought that I wanted to be.

I grew accustomed to dealing with people with quite large egos, and I never came along with my own ego. I was quite young as a photographer back then, so I was very much always feeling slightly out of my depth at that point. With time, I realized I didn’t want to be in this world of celebrity portraiture or taking on these types of commissions. I wanted to take portraits on my own terms.

If I felt like a portrait was appropriate because of the character of the person, I was so drawn to taking their portrait, but I couldn’t say no or I couldn’t stop myself from asking them to have the picture taken. Whereas previously it was like, “You’ve got 20 minutes. You’ve got to go to the home office to photograph the Deputy Prime Minister”. So forced into these situations where you learn to swim. Otherwise, if you start sinking, you’re in deep trouble because you’ve got 20 minutes with this important person who’s going to move along.

It’s very difficult to form any relationship at that moment, especially if they have an entourage of people. I didn’t like the immediacy of it— the rushed nature and almost being forced into these situations. I think I did really well, but gradually, with time and experience, I decided to naturally put myself away and approach subjects when I chose to.

The rebellious city of El Alto, Bolivia.

LATINNESS: I come from the editorial world also, so I know the feeling. Now, with this project, Cristy and I can choose the people we want to interview, and it makes all the difference.

NICK: You’re in control. I remember once being in a school in the middle of Essex, and there was a Conservative MP that went from Conservatives to UKIP (United Kingdom Independence Party). That was the big story— that he moved from sort of right leaning conservatives to further right. He had quite contentious views and he was seen as the savior of the country. They sent me along on this commission with lights, a chainmail and a hat and broadsword. So he was meant to be the savior of the country.

It turns out he had a Public Relations person with him, and I was having to persuade this man to put on the knight’s outfit for the front cover of the Sunday Times magazine. He didn’t want to put it on, so I was in this position where you’re just like, “I don’t want to do this. You don’t want to do this.”

That was one of the turning points where I was like I’m going to move away from this. It was a long time ago, but a good marker for me to move away into documentary and trying to create senses of places. Longer form storytelling, basically.

LATINNESS: You’ve described your heritage as a backbone to your photographic practice as an artist. It seems like photography opened a door to your father’s homeland Bolivia.

NICK: Bolivia came much later in life to me. I didn’t start traveling back properly until I was about 21, and, at this point, I was studying photography, finishing off my degree and just going out into the world as a photographer. Before that I’d been to Bolivia once when I was four years old, so I had this sort of painted picture by my family about that long trip we did to South America.

By the time I arrived when I was 21– after my dad spent most of his life in Europe– I was there on my own terms as a very young photographer. Everything was a sense of discovery for me and trying to establish where I belonged in this place. I didn’t speak Spanish— I still don’t speak Spanish– but I’ve managed to achieve lots of things without a sense of language. I think photography was my form of communication in a continent which I knew very little about, and it gave me the ability to travel and discover.

To begin with, it was very much about understanding part of my heritage. Later on, it became about me trying to give a voice to this changing country as Evo Morales was coming into power. The indigenous people had a sort of a platform to be able to form a voice and create a wealthier society for themselves. There was a lot at that point, around the 2005 mark, which made me want to go back and actually start making stories about this very rapidly changing Bolivia.

I was trying to discover what this country was all about. From my youth, my father would tell me about all these coups and puppet governments that were in place, and just very much a country for the elites, not for the people. It was just so well timed– my photography was beginning to happen in a time where the country was changing so much.

I think the two coincided at that point, and it became about pinpointing stories of indigenous groups, and specifically, looking into places like El Alto, just on top of La Paz, where the indigenous population was changing rapidly and forming a middle class society where there wasn’t one before. A lot of my work looked at those changes. It was a story of hope and less of despair, which is something which I was trying to shrug off in terms of what I had as a perception of what Bolivia was. So the two coincided nicely for me.

‘Ciudad Rebelde’, in El Alto, Bolivia.

LATINNESS: You explore the concept of foreignness and belonging in your work. What was it like growing up in the UK? Did you feel more British or Bolivian?

LATINNESS: Very British. I remember when my father used to drag us to the embassy parties and they’d pull out the panpipe music. The traditional folkloric music would be there, we’d eat salteñas, and eventually we became accustomed to that food.

My father was very chummy with the Bolivian elites that lived in London, so we’d meet the wealthier Bolivians, but that was not by choice. My father, funnily, when he went back to Bolivia as a different, more European person, shunned all of that, as well. He shunned his elite family past, and hated this attachment to where he had come from. He started rallying for trade unions and actually became very supportive for the indigenous of problems that were still felt while things were changing quite rapidly. There were still lots of arguments to be had as the population was readjusting to its new government.

I think my sense of Bolivia was formed in two stages. As a child, being taken to these strange events, when actually the reality of Bolivia was very different. You know, it’s something I felt more familiar with. It started to make me want to come back again. Eventually, after a number of years, my grandmother and my father died. I didn’t really have that much family left, so I still have this deep rooted urge to keep visiting and making work there, even though I don’t really have any blood family left in Bolivia.

My relationship is now my own. It’s not a family reason to go back, so there’s still definitely a sense of discovery and making work there and understanding a broader Bolivian consciousness of how the population feels and acts. It’s part of the body of work which I’m working on at the moment.

‘The Bitter Sea’.

LATINNESS: Tell us more about what you’re working on?

NICK: The project I’m working on is called The Bitter Sea, which is about the relationship Bolivia has with the ocean. It’s more about the sense of loss of something and how the country, as a collective, feels about that sense of loss. How it commiserates and celebrates its historic past.

Yet what that project turned into more about, is actually my sense of loss of my family, which I’ve lost there in the last number of years. It’s a personal discovery, again, like going back to me discovering how I’ve lost the parts of Bolivia, which was once about me going on holidays to Bolivia when I was in my twenties and enjoying these very family-led trips with some photography on the side.

Now it’s all about the photography and sort of using the story, the soul narrative of the ocean and the kind of the consequences of the loss of the ocean to me, to discover myself still and put myself in that frame.

From ‘The Bitter Sea’ Project.

LATINNESS: I assume the majority of your audience is European-based. Throughout this personal discovery, you’ve also told the story about a country that’s somewhat unfamiliar in your part of the world. What’s that reception been like?

NICK: I mean, people are so familiar with Peruvian cuisine, and on the global scale which that sits. I’m constantly bashing people’s heads, but Bolivian food is equally as good as the Andean ingredients are the same. There’s this growing culinary thing happening in La Paz, there’s just a lack of global awareness that Bolivia has as a country.

It previously always had a reputation of being the underdog or the poorer country, but it shares so many geographical elements with Chile and Peru, those Andres-focused countries. So a lot of my stories are unknown, although in recent years I’ve found a lot more foreign photographers go in there and make it work, and come out with stories about cholitas who climb the Andes and the indigenous dress.

I also struggle with my own reasons for coming in as a foreigner and approaching a subject which isn’t strictly mine, and how I reappropriate something. Obviously I try to think a lot about not glorifying. I want to be humble in these situations. I don’t want to come and take somebody’s identity and reform it– which I’ve seen happen– and turn it into these Westernized visuals like “Oh! So folkloric and indigenous. Look at the colors, look at these women who are climbing mountains!”

It has to be treated really carefully, especially myself, because although I claim to be half Bolivian, I feel very British, and that’s always at the front of my mind with how I approach stories about Bolivia. Why do I have a right to be there? But then I do, because I have an identity of my own to answer.

There are still lots of questions which are unknown to me: What’s my place? What’s my children’s place going to be in Bolivia? How are they going to travel there without having a blood family? I want them to have a relationship early on with South America and understand that culture, which I didn’t have. But, as of late, I feel like I have a strong knowledge of politics and culture that happen in South America now, and in a way, I feel sort of confident that I can talk about it, or criticize it or also, support it.

Different politics happen in different parts of South America, so I feel like I’ve been enough now and spoken to enough people to, at least, form an opinion on the matter. It doesn’t come lightly though. I’ve seen many photographers go to Bolivia, grab that story and then disappear. They recognize a visual story or some narrative that suits what they would like to do. They come to take the pictures and then not to be seen again. So I’m cautious of that.

‘We Feed the World’, a series on the sustainable life of a Quechuan farming community in El Choro.

LATINNESS: How do you define the difference between photojournalism and visual storytelling?

NICK: Well, I’m not there to photograph a moment. My eye is, I guess, slow and wandering. Although I classed myself as a documentary photographer, storytelling is a large part of what I do. I’m not defined by a moment or a time period.

A lot of my storytelling evolves, and it requires a deeper sense of repeatedly going back. It’s not there to sort of draw a line under the sun on an event based path, which lots of photojournalism does. I’m almost looking for my pitch to be timeless, in a sense, so that it all fits within the wider narrative. It often comes back to me, telling a story as an artist.

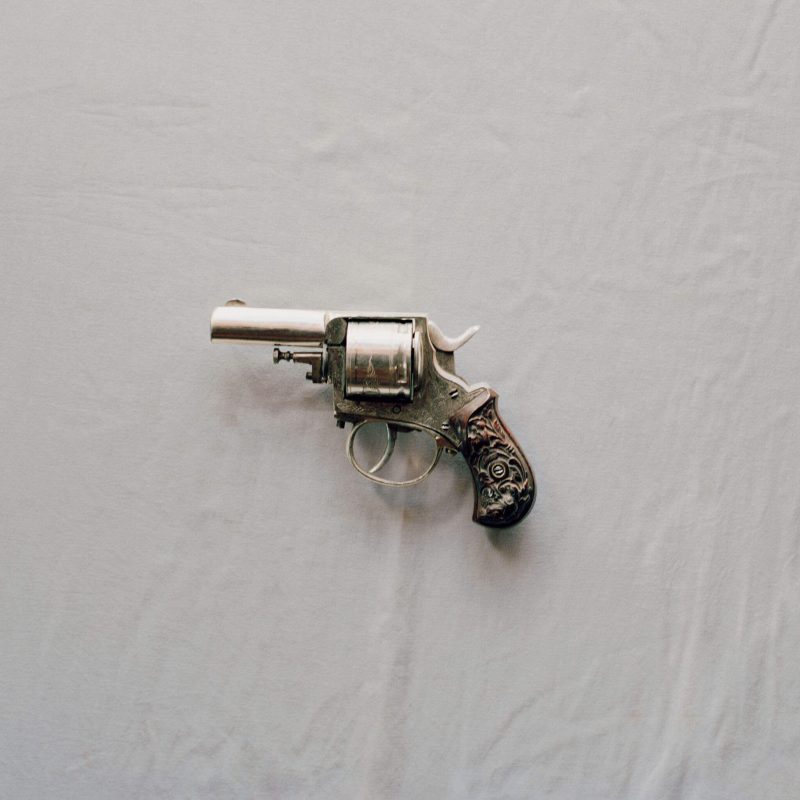

I think a good example of this was when I photographed the historical Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, which was a personal take on following the stagecoach robbers through the South of Bolivia, following in the myths and stories that led them as they were on the run from the Pinkerton Detective Agency. I was there with a very loose narrative of following the landscape they would have taken as armed robbers, but there was an element of truth and there was the loss of myth. I was there presenting my own version of the story, and I remember when the pictures eventually got shown on Time Magazine Lightbox (section) in the States, there were lots of historians sort of analyzing every artifact which I’d photographed in a museum in a silver mine, saying: “This is not the right revolver from that moment”.

I wasn’t there to present an accurate rendition of their story, and I wasn’t thinking too deeply on the facts because I actually preferred the myths behind where they rode, the places where they got killed and their supposed cemetery, which probably wasn’t where the gravestones were. In that storyline, I wasn’t there to factually represent what the truth was, nor looking to define what that truth was.

I think as an artist, there’s an element of fluidity. I’m making my own interpretation of the events. The same with Bolivia– when I go there, I don’t profess to know everything and understand every part of the country. I still regard myself as a foreigner in that country. Although I’d like not to be a foreigner, I’d like to be more invested in what’s happening and to have built an eventual name for myself in Bolivia.

‘Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’ in the South of Bolivia.

LATINNESS: Have you shown your work there as an artist?

NICK: I’ve had a number of exhibitions in some galleries in Bolivia, I don’t have a reputation probably in Bolivia itself. I’m better known in Europe and America. With time I’d like to produce and publish work and gain some sort of traction as a Bolivian artist, as well.

You know, that’s a long road, and Bolivia doesn’t have a contemporary arts background. Although it has a number of galleries in the richer parts of the country, it’s very much a new thing. I’ve shown in a couple of the sort of more contemporary galleries and alongside some other artists. So I have done parts, but I think most of my reputation belongs in the Western world.

‘Casa de Amor’, the love garages of Cochabamba, Bolivia.

‘Ekeko’, El Alto, Bolivia.

Nick Ballon in Bolivia.

LATINNESS: Both of us live in Latin America as you know, and what we find intriguing about your photography in the region is how you capture such clean images despite photographing in locations known for their vivid color and boisterous backgrounds. It’s really a beautiful balance. Is this intentional?

NICK: Yeah. For me simplicity in composition is quite key, and I’ve always tried to restrict color palettes, especially when in Bolivia. I’m very cautious of the typical Andean colors which present themselves all too often, and I’d much prefer working with a simplified color palette and very minimal compositional elements so that it gets restricted down to the only big elements which I’ve chosen to be in that image, and I guess, humbling the image itself.

It’s me trying to avoid all the sort of the signature images or kind of tones that historically Latin American photographers would use in their images, which are very understandable to the Western audience, but I’m trying to present Bolivia with a new light, with my eyes and way I might treat a subject here in the U.K. It’s a consistent theme through my making of images.

‘¡Viva Las Luchadoras!’ The Wrestlers of El Alto, Bolivia.

LATINNESS: It really strips away the noise and helps you tell your story much more clearly.

NICK: Simplicity is really key to a lot of my images. One of the pioneer photographers that I’ve always kind of admired is an Italian photographer. He didn’t have a reputation until he died: Luigi Ghirri. He wrote very fluidly about photography, but his work itself has such a subtlety to it. It’s very quiet and makes you think about the image a lot more.

I take a lot from his work and it puts you in a position of calm, which is the way I try to approach my subjects, from a position of calm. I guess this image, which happens to be just behind us, is probably a really good example of that. Carmen Rojas– I think that’s what her name was– she is one of the luchadoras who wrestles in El Alto, and I managed to get backstage to take portraits of the wrestlers before they went on stage.

I wasn’t interested in the noise and the wrestling and the action. I was interested in the moment before this spectacle, which takes place every Sunday afternoon up in Atlanta, where there’s screaming crowds of people watching. The ladies essentially wrestle against the bad guys. I love this poise, because it was all about her. It wasn’t about what she did, although she was this sort of hard-ass kind of tough lady who would pulverize Frankenstein to jump off these high ropes, but the image is the complete opposite of that.

LATINNESS: You’d never imagine she was about to fight.

NICK: It’s this very poised, quiet woman who was anticipating this. It was part of a series, so this is one portrait from that, but I think this sums up the level of quietness which I like to achieve in a portrait.

‘Ezekiel 36:36’, documenting the remains of a Bolivian airline.

LATINNESS: Nick, we actually discovered your work on Instagram. What’s your take on photography in the social media age?

NICK: I take it as a tool. I use it as a place to share the workings of something. I very much use it as an in-between space to show. Also more so as an educational tool to allow people that follow my work to kind of better understand processes and thinking behind how the images are made or where they’ve come from. It’s an incredibly useful tool, which I probably use more as a work tool, rather than an actual place to show finished work. It’s very restrictive in lots of compositional ways and I don’t think it shows images in the best way, but it’s a useful tool for me.

Kind of a communicating tool to be able to get people to see my work in places where I want them to see the work, be it an exhibition or in a magazine where it’s printed. I think I’m sort of old enough as a photographer to really appreciate the benefits of print still, and as much as possible, whenever I have opportunities to work with printed magazines or having my work published in longer form kinds of places, then that’s ultimately my end game.

I’d much rather work for not much money knowing that the work is going to be well published and printed in beautiful magazines and exhibit my work. Books are much longer in terms of the timeline of getting them into a book, but I find magazines quite an immediate kind of place to show feature length work.

LATINNESS: Do you have a favorite camera?

NICK: Yes. I’m less attached to cameras now, and I see them more as cameras for the right job. Quite often, in the last few years, I’ve been climbing lots of mountains, so heavy cameras tend to be a pain in the neck. If I’m working for myself, I always go back to the Pentax 67, which is an old medium format, six by seven former camera, which is bulky and slow.

I love working in slow ways and anything that makes me stop and think a little bit more about the image I’m about to take. Also, the fact that I only have ten frames instead of unlimited frames is a good thing.

Wherever I am, I’m happiest when I’m working in a slow, considered way and not being rushed, which goes back to when I was talking about portraits and, I hated the idea of only having 15, 20 minutes with somebody when I’d much rather build relationships and work on longer form kind of stories.

Behind the scenes of ‘The Bitter Sea’.

LATINNESS: Do you have a dream project?

NICK: Yeah, it was The Bitter Sea project, which has been a long time in the making because, as you probably both well know, life gets in the way. I’ve had a couple of children, and I’ve had a change in my relationship to Bolivia as my grandmother and father died within the last seven years. So I’ve been really thinking about what South America means to me, how I keep going back, and what that’s meant for a project I started a long time ago.

Amalgamate is about how that’s changed because I’ve changed a lot since. With the children, it straight away means I have less time to myself, so I can’t easily go away for long trips. South America or Miami would be fine, but with children it’s difficult. Now that I’ve had this sort of loss of my bloodline and my family in Bolivia, I’ve had to rethink that relationship with South America. So the whole point of that project has changed, and now I’m looking at it from my own perspective and how through this project, I work through this loss of my family.

Images courtesy of Nick Ballon.