A COFFEE WITH

OMAR Z. ROBLES: “WE CARRY THE MUSIC WITHIN US”

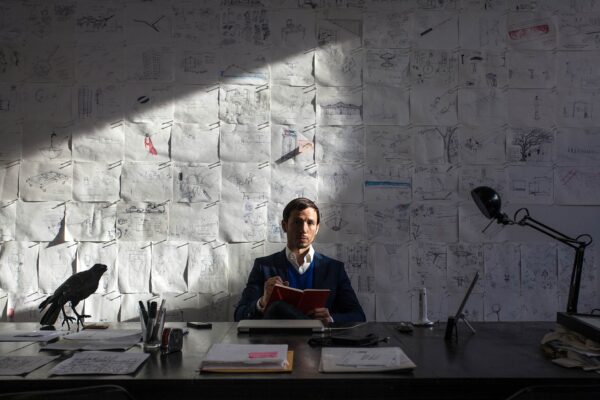

Name: Omar Z. Robles

Profession: Photographer

Place of birth: Puerto Rico

Zodiac Sign: Virgo

Instagram: @OmarZRobles

LATINNESS: Omar, first we’re curious to know if you have any artistic antecedents?

OMAR: Like many people, my story went around a lot, but if I’m honest, I wasn’t raised in an artistic environment. My mother is a Spanish teacher in Puerto Rico and my father is a doctor, and although he did sing and my grandfather loved music trios and Los Panchos– you know how it is- it was never something that was instilled in me, art as such. I eventually discovered it, but it wasn’t what I wanted to dedicate myself to initially because it never was instilled in me.

LATINNESS: So when was this artistic instinct born?

OMAR: At 16 I discovered theater, and specifically mime. I began studying it and preparing myself in different workshops. When I graduated from high school, I started a degree in electrical engineering because I had to study something, but by that time I knew I wanted to become a mime. My family disagreed and made my life miserable, so I continued with my degree for two more years, but was extremely unhappy, depressed, a horrible thing. I told myself, “Well, let’s make a deal,” and found graphic design. It worked for me because I liked computers, but it wasn’t something I was necessarily passionate about.

Again, it was like an in-between because what really drew me was the theater. Until finally, one day, I said: “No, too bad! I’m going to study theater. What my family thinks, well, what am I going to do, but I’m going to do it.” First, I came to New York, where I spent almost half a year preparing, and then I went to Paris, to Marcel Marceau’s school. I stayed there for two years. Once I graduated with a diploma, I left for Poland, where I lived for two years in Warsaw working as a mime, teaching and doing my show. Then my visa expired, and despite trying ways to renew it, I never succeeded, so I decided to return to Puerto Rico.

LATINNESS: Mime, electrical engineering, graphic design… When did photography enter into the picture?

OMAR: I always liked photography, but I never saw myself actually making a living out of it. I took one, two classes, and my teacher really liked my work. It gave me a lot of encouragement and very good direction, and I began to dedicate myself to it little by little. My brother is a journalist and he worked for a lifestyle magazine in Puerto Rico. They covered a bit of everything, it was like a merge between lifestyle and business.

I started covering social events for them, and then they assigned me interviews and editorials, until I finally did fashion photography. And well, that’s how I came to that world. Then I moved to Chicago, where I started doing headshots for the theater, because I continued with theater, and also worked with Hoy, the Spanish-language newspaper of the Chicago Tribune. One day I thought, “Well, I do a lot of professional work, but not artistic photographs. If I want to call myself a photographer I should have a portfolio of my own, apart from what is assigned work.” So I started with street photography, documentary photography to capture the city, the things that happened in it, the people, etc. That’s when I began to develop a passion for cities, for the spaces where people live.

Coincidentally, while in Chicago and shooting street photography, one day I came across some kids doing Parkour, which is basically a sport (although I see it as more of an art) that combines gymnastics and acrobatics with street elements. Parkour was developed in the French army as a technique to cross from point A to point B in the most efficient manner possible. I knew a little about it, but had never seen it in action. “Wow! This is impressive,” I thought, “to use the city as a different space than what we see every day.”

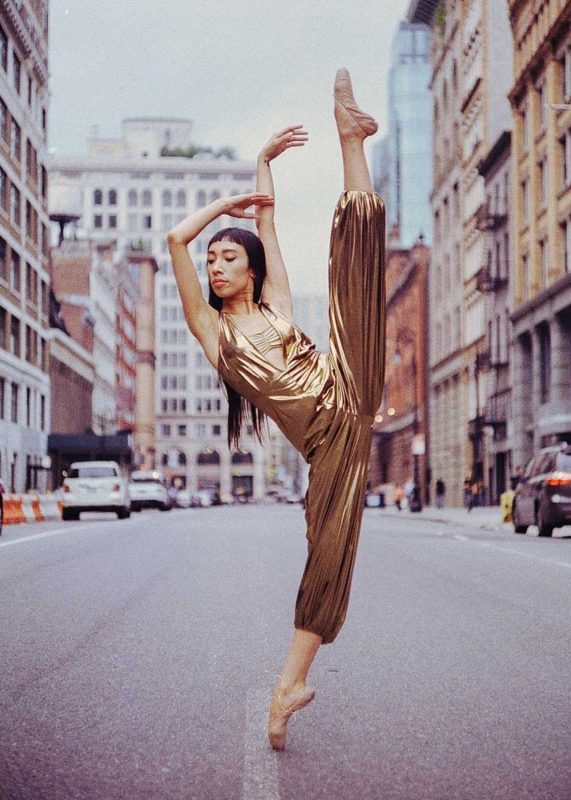

When I returned to New York, I continued to work with some who practiced Parkour in the city, and one day I said: “Something is missing here.” I drew upon my artistic background of mime, and it occurred to me: “Why don’t I mix street photography with mime, myself being the subject?” Interweaving these two environments, I began to make a series of self-portraits where I put the camera on the streets and executed stylized movements, jumps, etc. A combination of Parkour with mime and street photography, using the street elements. Then, when it started to get a little more complicated for me, I began the series of photographs with the dancers.

The series started taking shape, and it was like a snowball effect. I photographed one, then she referred me to her friend, and so on until different media outlets, such as Mashable, began to share my story. Instagram featured me with a profile and an interview, and it became what today is the basis of my work.

LATINNESS: Did this type of photography already exist at the time?

OMAR: Well, yes, there is photography of dancers, and dancers in urban spaces from the 1920s, or perhaps, at least, from the 1940s. What distinguishes my work from that of others in this realm is the knowledge I have of the body since I was a gymnast, a mime and also studied ballet. So when I direct the dancers, I really do it from a choreographic point of view, not just a photographic one. I don’t say: “Do whatever you want and I’ll capture it,” but something more like: “We’re going to do an arabesque, and now move here, move here …” I am almost a combination of choreographer and sculptor, varying the pose until we get to what I want.

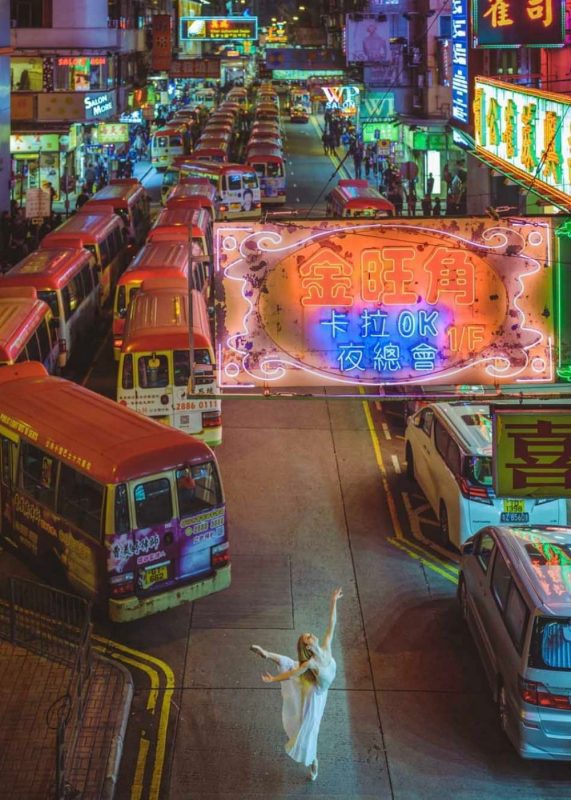

Another thing I’ve tried to achieve with my work is combining the worlds of street photography and documentary photography, using the space as it exists without trying to alter it, without adding other elements to give it flashiness. I use the scenery as it is, I don’t add anything. The story is already there, it’s really getting into it, and that’s why sometimes when people react, I use that inside the photo. Sometimes you see trash and passerbys try to pick it up, I stop them and ask them to leave it. That’s what defines my style as such, what separates me from another photographer.

LATINNESS: You’ve traveled to many cities for your work. Which has been your favorite to shoot thus far?

OMAR: Cuba is still my favorite. It has many special things about it: the visual quality, the quality of the people and, above all, the quality of the dancers. It’s really something impressive.

LATINNESS: And any city on your bucket list?

OMAR: There are so many! I’d like to cover a large part of Latin America because I’m interested in showing ballet from this part of the world. When people think of ballet, they always refer to Europe, the United States, Asia or Russia, but almost never to Latin America. The region has really good companies, but since it doesn’t have the resources to go on tours outside of its countries, as ABT (American Ballet Theater) does, they stay there and people do not know of the great talent that exists.

However, in most international companies, many of the main dancers are Latin: Cuban, Argentine, Mexican, some Puerto Rican. Latins have a talent for dance and ballet, because, as we say, we carry music within us, which is why I would like to give them a little more light.

I would also like to return to Paris. I encountered the city as a mime, but not yet as a photographer, and for me it’s a very special city because it formed me; I had never lived alone outside of Puerto Rico until I arrived in Paris on my 22nd birthday. This transformed me into a man, an adult and an artist, in many facets.

LATINNESS: Now that we’re on that topic- you’ve lived in Paris, Chicago, Puerto Rico and New York. How have these cities influenced you personally?

OMAR: Well, there are many things. As for my upbringing in Puerto Rico, the history of colonialism is part of one’s identity, and it’s very difficult to shake. In Paris, for example, one of the things that transformed me the most was confronting all that colonialist baggage I carried, which makes one think that what is outside is better than what is inside. Sometimes one tends to despise oneself for being from the colony, but being in Paris really made me confront that, like now you’re in the big leagues, you’re in a big city, you have to move forward.

In Puerto Rico we care about each other; you see someone and ask, “Are you okay?” That’s very Latin, and in France it’s like to each his own, and it can feel like nobody cares. Those kinds of things shaped me. Then, being here in New York, one of my biggest struggles has been the fact that “everything’s so great” and people are not very critical. As an artist, sometimes you struggle a bit with that because in France, it was the opposite. Everything is like “c’est pas mal”, like it’s not bad. The best thing is to find a balance in which you can be self-critical of your work and critical of the work of others, and differentiate between what is good, what is bad, what can improve or what needs no improvement. As an artist, you are always in that dichotomy.

LATINNESS: How do you choose your subjects and locations?

OMAR: Wherever I go, be it here or when I am working internationally, I don’t choose obvious locations, in the sense that I’m not looking for a specific attraction. For example, if I am in Paris, I most likely will not photograph the Eiffel Tower because I am not looking for those classic spots, but the places where the locals are, where you find the everyday man.

Of the places I’ve always loved to capture are markets, because they show a culture through food, colors and what people buy. For example, in Hong Kong, there are these giant electronic marketplaces. It’s a matter of walking, exploring and seeing things in the moment. I generally meet the dancer at point X, and from there, we walk and explore. I don’t come with a script because the times I’ve tried, it always fails. It’s better not to have a predetermined story and to be open to what appears.

As for the dancers, I take on the task of literally stalking them on Instagram and figuring out their skills. I do a proper investigation, I go to their page and see the photos they have to analyze their technique.

LATINNESS: Why do you think there is this universal fascination with ballet?

OMAR: On a photographic level, ballet teaches you, in a way, how extraordinary human beings can be. We are used to seeing life on the street where you walk, and your legs are for walking, and your hands are for holding things. Ballet breaks with that idea, and almost gives you the impression that the legs are for flying and hands are for lifting them, to feel life.

Obviously, there are many other styles of dance, which I think are a little more difficult to photograph, to capture, in the clearest and most obvious way, how stylized they are. Ballet is so stylized. When you capture a grand jeté, for example, in which the person is in the air with their legs fully extended, that changes and redefines the social paradigm in a certain way. When I do it on the street, it’s like saying to people: “the street does not have to be for walking only, it can also be for playing, for fun.”

LATINNESS: Omar, what inspires you?

OMAR: I am inspired by the impossible, by what I’m most afraid of, by doing what is difficult. The challenge of overcoming that, of winning, is what inspires me. For example, street photography was one of my greatest challenges because I love speaking in public, as well as for interviews, but a more intimate issue, a face-to-face meeting, talking with someone one on one, gives me a lot of anxiety. When I started, it was a way of challenging myself and saying: “OK, you have to come out of that shell and overcome that fear.” That was precisely the reason why I started working in analog. I had never studied analog, I started in digital, but I looked into analog because it was a way of saying: “This looks difficult, I know it’s more complicated, I’m going to do it.” Right now, I’m developing my own photos.

LATINNESS: How did Conversations with Dancers come about? Is it something you were previously working on or a pandemic project?

OMAR: A little of both. I always wanted to do something where you not only view the image of the dancer, but also discover his story. I’d thought about making videos, and actually tried when Instagram TV started, but if I’m 100% honest, I hate making videos because what I’m passionate about is the moment of directing the photo. When the pandemic started, I thought it might be an option, and that’s where the idea of conducting the interviews came from. I said to myself: “Maybe this is a good time to do something more comprehensive where people get to know the dancers from a personal point of view.”

It has been super enriching, because not only have I become more acquainted with the dancers, but I’ve also learnt more about myself, and been more appreciative of the relationships I’ve developed with them. While interviewing some dancers I thought: “Wow, I started photographing this kid at 18 years old and he’s already 24!”

LATINNESS: Do you have plans to continue this project once the pandemic is over?

OMAR: For the moment, yes. I want people to know that the dancer in front of the lens is more than a pretty pose, it’s a person who has dedicated his whole life to doing that job, who has high hopes, many dreams, but also has sacrificed a lot to achieve their goals.

LATINNESS: What is the greatest piece of advice you’ve received during your career?

OMAR: A lot. The first was from Marcel Marceau, which is that we do not make art just to impress, but to move emotionally. That was what he wanted to achieve. I’m not doing this to impress anyone, but really to move the public. I want people to feel something inside, because what impresses is forgotten, but what moves you, stays with you and transforms you.

Another piece of advice was given to me by one of my photography teachers. He said to me one day: “Do you know what the secret of great photographers is? That they only show their best work.” It’s super simple, but the reality is that we all do things that are not very good, the important thing is to have a self-critical eye and say: “What I did is bullshit, let’s stop and try harder.” Oftentimes I say this joke: sometimes people treat their artistic work like their children, they think they are all pretty, but in reality, some are not.

Images: Courtesy of Omar Z. Robles for sale in https://www.omarzrobles.